American Film Company

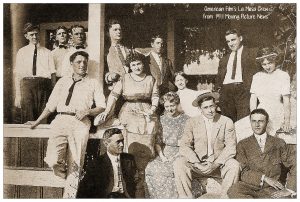

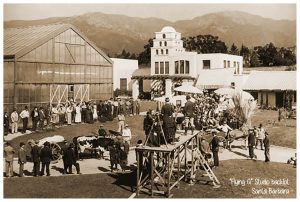

Chicago, Colorado, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, San Juan Capistrano, La Mesa, Santa Barbara

Click to enlarge

Related Pages:

Offices: 312 Ashland Block Bldg. Chicago, IL

Active 1910-1913

Offices: and studio 6227-6235 Broadway St.

Active as studio 1913-1916

Active as Company offices: 1913-1920

In the beginning

Chicago based American Film Manufacturing Company was born out of necessity. They always seemed to struggle. For a place in the industry, for good distribution of their movies, and for a place to make their movies. They moved from place to place finally settling in Santa Barbara where they set up one of the world's largest movie making studios and, for a time, experienced huge success.

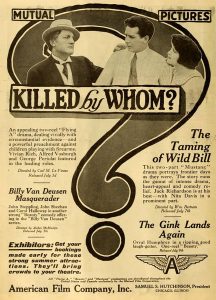

The company was founded in 1910 by four Chicago businessmen, Samuel Hutchinson, Charles Hite, Harry Aitkin, and John Freuler.

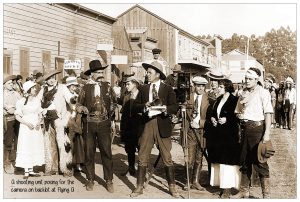

Early film making was like the wild west. They seemed to spend as much time running from the law as they did making movies. The early studios were wild cats. They would pile out of a car, set up a camera, film a quick scene, then pile back in the car and drive off before they got caught. This scene played out all over the movie centers of the day.

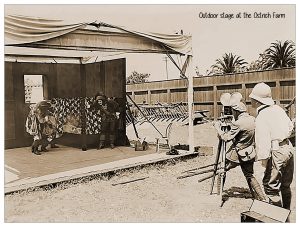

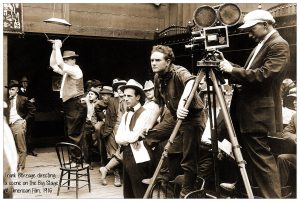

To film an interior scene, they would set up a makeshift outdoor stage, decorate it with walls and furniture, and shoot while the sun was shining. Even the big companies operated this way.

H and H Film Service

Samuel Hutchinson and Charles Hite were two of the American Film Manufacturing's original owners. But before that, they owned a company they called, H and H Film Service (established 1906). Their position in filmdom was to buy the distribution rights to movies made by the largest studios of the day and then rent copies to theaters. Distribution companies, like H and H, were know as "Exchanges," and existed in every major city in the country.

H and H distributed films for the largest movie studios of the day. These 800 pound gorillas included Thomas Edison, American Mutoscope and Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Kalem, Selig, and others. H and H, in turn, rented those movies to their sphere of movie theaters all over the Midwest and beyond.

Click to enlarge

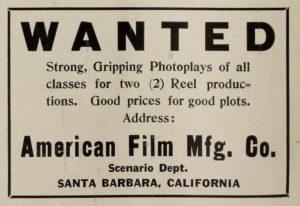

The company was founded in 1910 by Samuel Hutchinson, a local chemist , and Charles Hite, Harry E. Aitken, and John Freuler, all veterans of the movie exchanges. It grew out of a previous venture in the film distribution business and was born from a desire for greater profits by making movies for themselves. By 1912 the owners had also founded Mutual Film Corp. to distribute American's film product as well as the output of most of the independent studios and producers of the day. All four would go on to movie success after American closed in 1921.

American Film (born of necessity) vs. The Patents Trust

In 1908 those large movie studios that were supplying H and H (and other exchanges around the country) banded together in an effort to control the movie business. Led by Thomas Edison, they formed a partnership with intention of monopolizing the national output of film production. They formed the Motion Pictures Patents Company (known as the "Patents Trust") to pool their patents. The goal was to control how movies were made and shown by charging every other film maker and theater fees for using their patents. They wanted all movie makers to use only their cameras and all theaters to use only their projectors...at hefty fees. The Trust often tied other movies makers up in court, even when the equipment they used didn't violate a patent. Just the threat of law suit forced companies to either pay up or go out of business.

Then, in 1910 the Patents Trust companies also formed General Film Company. Over night they became the nation's largest exchange, controlling and restricting which companies could distribute their movies to the theaters. If a theater wanted to show one of their pictures, they had to rent it from General. These combined actions were done to force independent film makers and independent distributors out of business unless they joined their patents and distribution companies, paying hefty fees to participate.

H and H had 4 choices: sell out to the Patents Trust, let the Patents Trust force them out of business, continue to struggle as an independent distributor, or produce their own films for their own distribution. They chose the latter.

And thus, American Film Manufacturing Company was born. Their goal was to make and distribute their own movies and work around the Patents Trust and General Film. It incorporated in 1910 and started making movies in Chicago which were initially distributed by H and H. Beginning in 1912 they organized a successor to H and H, Mutual Film Corp. Mutual was formed by H and H and American Film's founders to distribute American's movie production. They also distributed the films of a group of other small studios wanting to maintain their independence from Edison and the Patents Trust.

American Film Manufacturing Company was initially headquartered on the Bank Floor of the Ashland Block, an early Chicago high rise building located at Randolph and Clark in Chicago's downtown area. Its first film was shot on the shores of Lake Michigan. At the same time they leased the studio of the defunct Phoenix Company at 1425 Orleans St. while building their permanent homes in Chicago and out West.

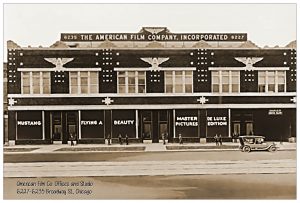

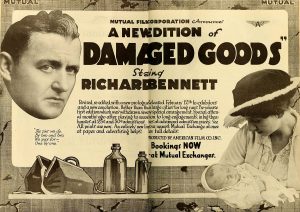

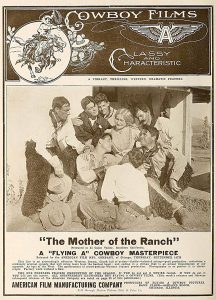

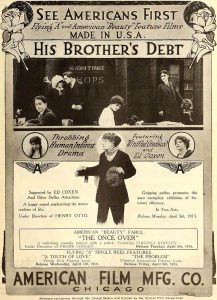

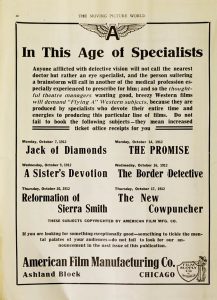

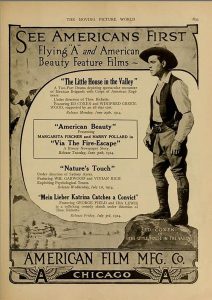

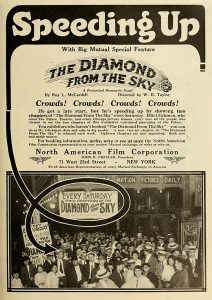

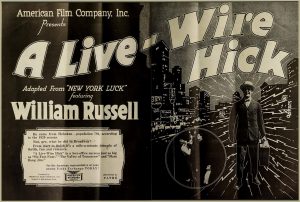

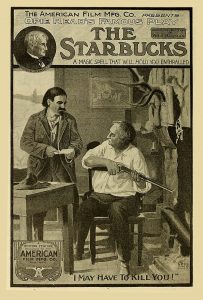

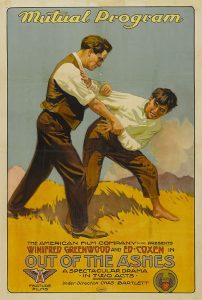

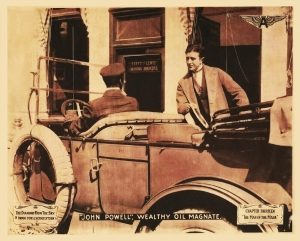

American Film Co. had several brands: It's flagship was "Flying A" which made mostly westerns (the most popular genre for its audience), but also shot under the "Mustang", and "Beauty" brands. There were several smaller brands that delivered only a few movies: "Deluxe," "Clipper," "Pollard," "Signal," "Santa Barbara," "Distinctive," "North American," "Masterpictures," and "Star." Each brand was used for different types of pictures. It also released pictures under the name of its two distributors, Mutual Film and Pathé Exchange.

The Chicago Studio

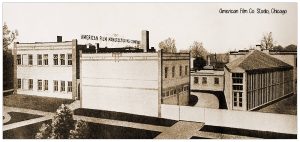

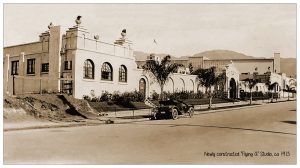

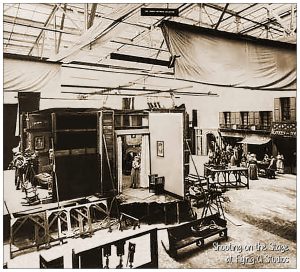

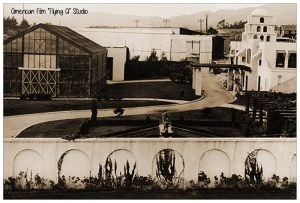

The Chicago studio was constructed in 1913 at 6227-6235 Broadway St. and consisted of a few small buildings and a small triangular glass stage. In 1915 they expanded the lot by moving several of the buildings to the back of the property and constructing a new administration and office building facing Broadway St. At the same time it dropped the word "Manufacturing" from the company name becoming the American Film Company. Shooting, however, was discontinued at the Chicago studio by 1916 but the lot continued in the role of corporate headquarters, publicity department, and and film printing lab.

The American Film Company had three shooting units: two operated out of the Chicago studio and the third traveled west in search of shooting locations to make cowboy movies. The two Chicago units shot at the Orleans St. rental studio and later at the Broadway St. studio. However, they mostly shot outdoors on location and the studios were rarely used for production. The dramatic unit was under the leadership of director Thomas Ricketts and the comedy unit was run by director Sam Morris.

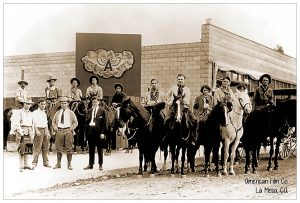

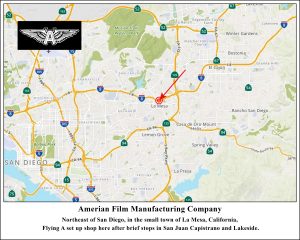

The third unit, under the direction of Frank Beal, made mostly Western. After brief stops in Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona, the Western company settled in San Juan Capistrano, California before moving to more permanent locations.

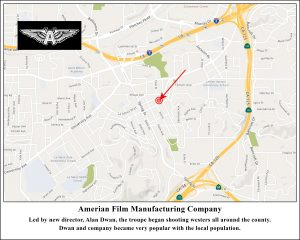

They land in La Mesa

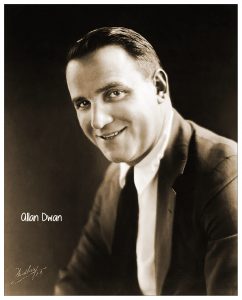

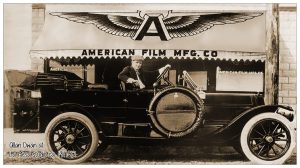

When film stopped coming from the Western unit in San Juan Capistrano, California, Samuel S. Hutchinson, company President sent Allan Dwan, a scenarist (aka screen writer) west where he discovered that director Frank Beal was drunk and AWOL, abandoning his unit, leaving them without money or any new product to show for their efforts.

Legend has it that Dwan (who originated the legend) wired Hutchinson saying "Suggest you disband company. You have no director, " to which Hutchinson replied "You direct." Dwan then said to his new charges "Either I am a director or you are out of work."

They went back to work.

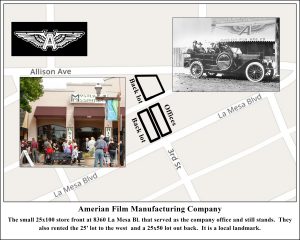

The company packed its bags and relocated south first to Lakeside (a small resort community) and then to La Mesa, where Dwan started American Film's first studio and the "Flying A" brand emerged as the company's most popular and profitable. Dwan rented the 25' x 100' west half of the brand new Wolf Building, next door to the local undertaker, on August 12, 1911. The small retail building that still stands today and is considered an historical location by the community. It served as studio, company office, film lab, dressing rooms, and more. They also leased the 25 x 100 lot to the west and a 25 x 50 foot lot behind them to serve as outdoor shooting area and storage. The company also leased a corral near the corner of Date and Orange (across from the Allison School) for horses used in filming their Cowboy and Indian movies.

The studio was opened even before American built their Chicago movie studio, making La Mesa the company's first actual studio.

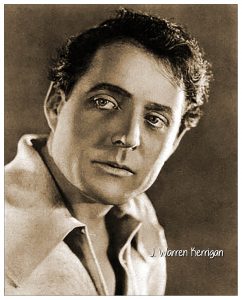

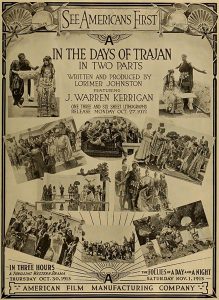

Dwan made over 100 Westerns at the little studio in San Diego County. The American troupe integrated well with the local community and was well regarded by its citizenry. Dwan became a popular, "colorful character," as did the company's leading man, J. Warren Kerrigan. During the La Mesa stay they took advantage of the variety of beauty and vistas shooting mostly outdoors around San Diego County.

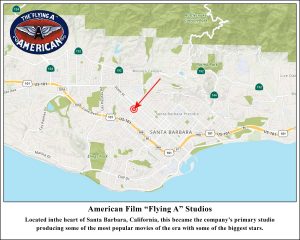

Up the Coast to Santa Barbara

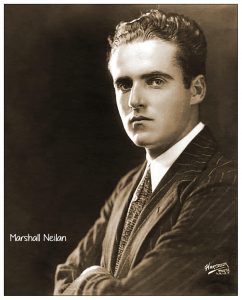

In 1912 Dwan felt he had used all the shooting locations that La Mesa and the San Diego area had to offer. Needing fresh locations, he asked future famous director Marshall Neilan to travel up the coast to scout out a suitable place to settle. Dwan, Kerrigan, Neilan, and the rest of the company pulled up stakes, traveled north and settled the Western unit in Santa Barbara. There he found a seemingly limitless number of great shooting locations, year round sunshine, a cooperative local population, and easy access to rail lines connecting them to the Chicago headquarters.

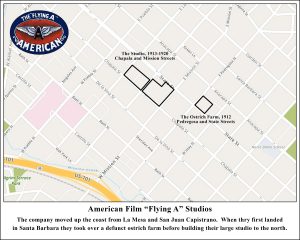

They arrived on July 6, 1912 immediately set up a makeshift shooting stage and headquarters leasing an abandoned ostrich farm (on the eastern junction of State Street Pedregosa St. just northwest of Islay St.). They occupied one fourth of a city block. There they turned out several one-reelers every week, putting them ahead of their scheduled rate. Since most of their shooting weas done on location, the small studio worked out well. It wasn't long before American set up a film processing lab on Cota St. instead of sending the raw footage to Chicago for processing at the company headquarters. With a local lab they could operate more efficiently and get their movies edited quicker and shipped to Chicago for release printing.

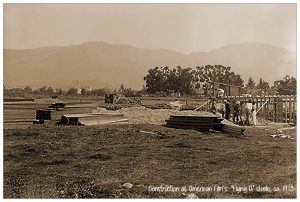

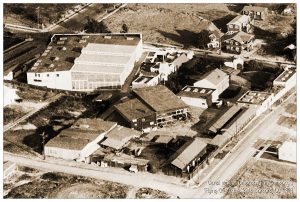

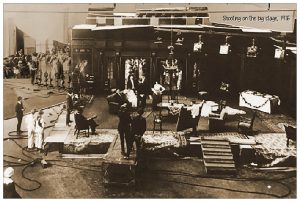

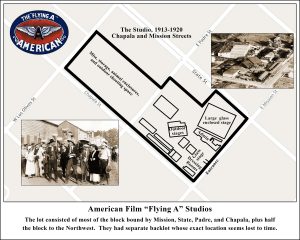

Needing more space, in 1913 construction began on a formal studio two blocks north, buying three large parcels in succession as their needs grew. The large plant was located on Mission St. bounded by State, Chapala, and Padre Streets and occupied 3/4 of the block This allowed them to make their one reelers at an even greater rate.

Though Dwan left the company around this time in a dispute with ownership, he went on to a long, successful career as a director spanning 6 decades, working for many of the major studios. Marshall Neilan also left the company and went also was a successful Hollywood director.

Future Celebrities who Passed Through Flying A

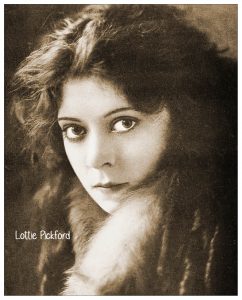

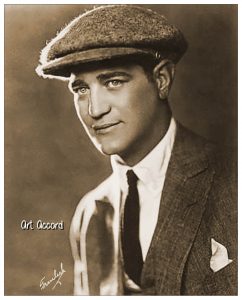

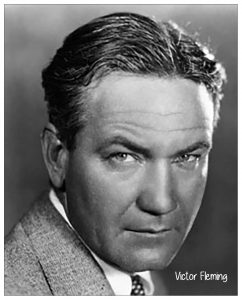

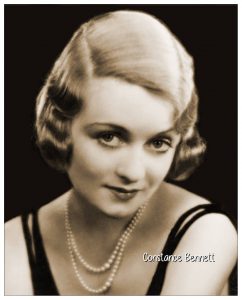

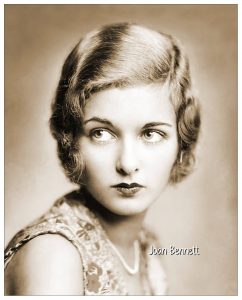

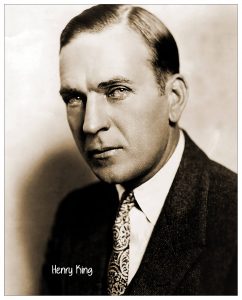

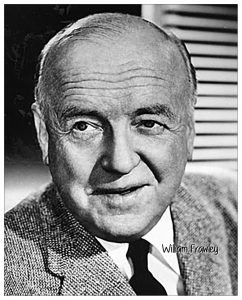

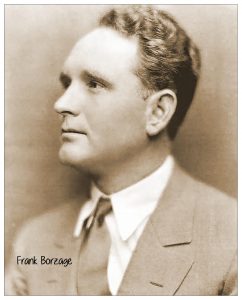

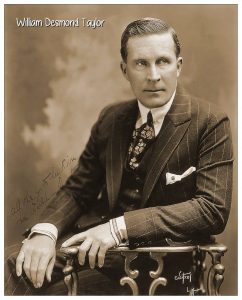

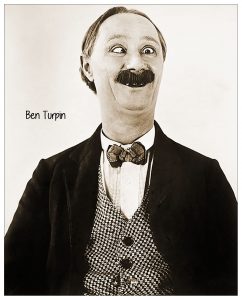

Many of Hollywood's great called Santa Barbara home before moving on to bigger things. Among them were Allan Dwan, of course, and Mary Miles Minter, Marshall Neilan and Lottie Pickford, J. Warren Kerrigan, Art Accord, Victor Fleming, Henry King, Frank Borzage, William Desmond Taylor, King Baggot, Constance Bennett, Joan Bennett, Helen Holmes, Lewis Cody, William Frawley, Wallace Reid, Ben Turpin, B. Reeves Eason, Henry Hathaway, Anita Loos, Leo Maloney, Harry Pollard.

The Studio Continues Expanding

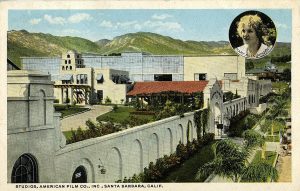

Even though two of the three shooting units remained in Chicago, it soon became clear that the Santa Barbara Westerns unit would be the most prolific, eventually becoming the company's only shooting unit. The Santa Barbara years were not only its most profitable and most prolific, it made American Films Flying "A' one of the true major powerhouses in the movie business.

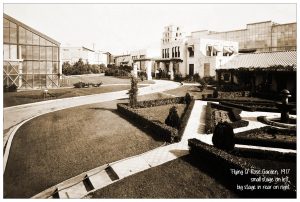

American Film's Flying A studio expanded rapidly. First they build a small glass stage and several support buildings, then a much larger stage. They consolidated the lab into the new lot and built editing suites, dressing rooms, offices, several outdoor shooting platforms, and a green room for actors waiting to be called to the set. It also included a rose garden, which is still there today.

Flying A's Biggest Star Comes to Santa Barbara

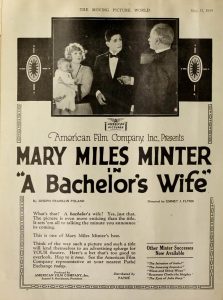

While most of the Flying A talent was home grown, Mary Miles Minter came with her very own pedigree, having been a child star on the stage, and already had leading roles in several motion pictures. She was considered Mary Pickford's greatest rival.

Mary signed a contract with American in 1916 and made 26 films for the company over three years before leaving for greener pastures at Paramount Pictures. Unfortunately her career was derailed at the age of 21 after being embroiled in Hollywood's first murder scandal (the murder of her director and lover, William Desmond Taylor). Mary Miles Minter lived well into her 80s.

The Chicago Studio Shuts Down

In 1916 American closed the Chicago studio. All company film production was permanently shifted to the Santa Barbara studio. At the time it was one of the largest in the world. While the acting company was out on the West Coast, company offices and day-today operations were consolidated at the Chicago Broadway Street facility. Business operations, promotion, film processing and printing continued to take place in Chicago.

The years 1913 to 1916 were peak years for American Film Co. Output was at its zenith. According to Samuel Hutchinson the company had doubled its output in 1915 and tripled it in 1916.

The Beginning of the End

Even though the company was doing well by this time, the movie business was changing. American Film Co. had trouble keeping up with it. Though American Film Co. had banner years of success between 1912 and 1916, the next several years were a struggle and the Flying A would not survive.

There were several reasons for American's demise, all of which created a perfect storm that the American Film Company was never able to recover from. It was never a matter of reception by the film going population. In fact the public loved the Flying A movies, they were well received. The problems were strictly business, the same problems that many of the early movie makers suffered from.

There were Several Reasons American Struggled

A large percentage of American's revenue came from overseas sales through their London distribution office, who sold American's movies all over Europe. War broke out in Europe in 1914 and WWI saw the beginning of the end of movie distribution all over Britain and the Continent. The American Film Co. was not the only victim of this, but because a disproportionately large share of the company's revenue came from European sales, and the market began disappearing, a slide began that accelerated throughout the war years and they were never able to recover.

Second, the domestic audience was clamoring for longer feature length movies, like Hollywood was beginning to produce. The company had only made short films up to this time for the small, independent theater market. Their transition to features was difficult. One reel movies, with as many as 10 or more shooting simultaneously, allowed Flying A to turn out a lot of easily sellable product that the Mutual Exchange had, up to that point, a ready market for. Feature films took longer to make, and were far more expensive, as much as fifteen times the cost of the one reelers. Because they were shooting fewer movies (only 2 or 3 at a time), many Flying A actors and crew fled to Hollywood looking for steady work, leaving the Santa Barbara studio without their best talent. Revenue was down, costs skyrocketed. Profits suffered. Plus, isolated in Santa Barbara, American found itself outside the mainstream places like Hollywood, Edendale, Fort Lee, and New York, so they had trouble attracting adequate talent and had few local film making business resources to draw from.

The third reason they struggled was distribution. Their distributor, Mutual Film Co., was at its peak distributing the one and two reel product of several small, independent film companies. As Mutual and American shared ownership American had regular distribution for as much as they could turn out, as fast as they could turn it out. However, a 1915 internal dispute within Mutual forced out the company President, Harry Aitkin. Aitkin, one of American's owners, also had ownership interests in other studios. Mutual installed of another American Film owner, John Freuler, as the new president. Aitkin formed a competing company (Triangle Pictures) taking some of Mutuals best producers with it and Mutual emerged in a much weakened position. It was not up to the task of giving American's Flying A the support it needed for feature distribution. Within three years, in 1918, Mutual folded.

In 1918 Samuel Hutchinson and American Film established a relationship with a new distributor, Pathé Exchange. Pathé, one of the oldest and largest film distribution companies, did not provide the same high level of support that Mutual did. Hutchinson felt it did not give American the same attention it gave its other production companies. American's movies were costing more to produce and were being shown in fewer and fewer places. Profits were down. While many studios entered into contracts with a variety of distributors, American's eggs were all in the Pathé basket, and their distributor was not adequately selling the American Film Co. product.

The Decline Continues

In 1917, Flying A let go a large number of its employees who went to Hollywood to continue their careers. They tried to continue with an ambitious schedule of features, but in 1918 and 1919 its best remaining talent, including their long time major star, Mary Miles Minter, and future Oscar nominated director, Henry King, left the company for greener pastures in Hollywood, leaving them without the talent to produce the quality product they needed and falling well short of their goals.

In 1920 production stopped altogether at the Flying A, the gates were closed. All the remaining employees moved on. They managed to live another year on their backlog of unreleased features and by reissuing older short movies. Though it announced new productions for 1921, the company closed and never shot another film.

The studio was torn down in 1948.