Selznick's Studios:

Clan Patriarch

and Court Jester to the film industry

Lewis J. Selznick

May 2, 1869- January 25, 1933

Sons David O. and Myron Selznick

Lewis J. Selznick's sons became luminaries of the industry, like their father. David will be best remembered as the producer of Gone With the Wind, King Kong, The Third Man, and Rebecca. Myron became a powerful talent agent. Among his clients were Katharine Hepburn, William Powell, Vivian Leigh and Laurence Olivier.

Selznick on Hiring Himself

at Universal

"This was duck soup for me. If they didn't know what they wanted, I knew what I was after, so I appointed myself to a job, picked out a nice office, and went in and took it. This got by with bells on. People came in and talked to me about everything that was going on, and pretty soon I knew all about it."

Lewis J. Selznick was described as the early movie industry's "Court Jester." The Jester is the only one in the court who can eat the King's food, drink the King's wine, sit on the king's throne, and make fun of the King by pointing out his weaknesses. That was Selznick's relationship with the movie moguls who reigned in the business.

One writer said: "...he's always exceedingly direct. He's quite as direct as a club."

Selznick developed a style of promotion unique only to him at the time, he was a shameless self-promoter and nothing was too outrageous in order to get his name in front of the public and the industry. Among his peers, he could go anywhere, say anything, and poke fun of and ridicule the other movie magnates, and do it in a way that the others would laugh along with him. He was a particular thorn in the side of the industry's two giants, Carl Laemmle of Universal and Adolph Zukor of Paramount.

Lewis J. Selznick, know as "L.J.," was one of many Jewish immigrants born and raised in poverty who managed to raise themselves to success and wealth. A number of them, like Selznick, made their way to the movie business.

Selznick was born in Lithuania (then a part of the Russian Empire) in 1870 and grew up in Kiev, Ukraine. He emigrated to the United States in 1888 and became a citizen in 1894. He left school at an early to learn the jewelry business in his adoptive home town of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. He married Florence Sachs in 1896. Together they had four children, two of them, Myron and David, followed their father into the movie business. Ruth died at the age of one, and Howard carried an undiagnosed mental illness all of his life.

Selznick and Universal

Lewis J. Selznick had been a successful retail jeweler in Pittsburg and moved to Brooklyn to open a new store. In 1914 he accidentally stumbled into a job at Universal Film Manufacturing Company (later called Universal Pictures). in Fort Lee. Here is how the legend goes.

It was just a couple of years after Universal's formation in 1914 through merging several small companies into one larger company. Wanting a movie job, Selznick walked into the New York offices of Universal to ask for an interview. What he found was the chaos of a power struggle between partners Pat Powers and Carl Laemmle, each trying to oust the other. The business was in upheaval, each partner both yelling at and avoiding the other. Sides were drawn, and the everyday employee was caught in the middle. Nothing was getting done.

Selznick, taking advantage of his previous trade, pulled out a few jewelry bobbles, and flashed them around. People were impressed enough to let him stick around where he had the time to size up the situation. Since no one was watching him, he picked out an office and put himself on the payroll. Real employees, not wanting to raise the ire of either Laemmle or Powers did not even inquire how Selznick got hired and if it was Powers or Laemmle that hired him. L.J. Selznick was in the moving picture business.

For several weeks Selznick watched and listened. He concluded that one thing the company needed was a general manager. So, he gave himself a promotion, had letterhead and cards printed, and began to run the company giving advice to the producers and overseeing the sales of the movies. He commanded authority while learning the business and the industry.

For a while, it worked, until Carl Laemmle thought he was a Powers ally and Pat Powers thought he was in the Laemmle camp. After months of power struggle, Laemmle won the war, and Selznick was fired. In the process, Selznick had begun to build a reputation in the industry. It is fortunate for the world that he did. And, Selznick's public needling of Laemmle would begin.

Selznick brings his own style to the movie business.

Selznick had always had a brash, outgoing personality. Some would call home obnoxious or pushy. It was his way of getting noticed. 1920s writer Terry Ramsey would call it "Selznickery". Selznick simply called it publicity. Shameless self-promotion. It was what made him successful in jewelry. It was what separated him from everyone else. He would just carry it on in the movie business.

World Film Corp.

Selznick had the movie bug. His stint at Univeral gave him an intimate knowledge of how the movie business worked and how movies were made. He made connections and learned who the available talent was, and began banging his own drum...as loudly as he could. He wanted to get noticed, and he succeeded.

His next move, in 1914, was to buy World Special Films Corp. out of Cleveland whose business was importing films from other countries. Needling financing to distribute his newly acquired What the Gods Decree, he invented some creative Selznickery. The film cost him $4,250 to buy. He needed to raise that sum back. So he called on bankers and financiers, with the goal of selling 99 shares of the film for $42.50 each (keeping a share for himself). The reasoning was that selling many cheap shares would be easier than selling a few large shares. He was right. Rather than spend a lot of time negotiating with Selznick and his overbearing personality for a bigger share, rather than try to acquire a larger percentage, rather than listen to one more minute of Selznickery, the financiers found it easier to write him a small $42.50 check and usher him out the door. Selznick made his money back, and the 99 backers each made a handsome profit. L.J.hand-picked a few of them to finance Selznick's future projects, including the formation of World Film Corp.

One of the largest half dozen or so companies for many years, Selznick formed World Film Corp. on June 9, 1914. He teamed with a variety of business, movie, and theatrical people, he rented offices in New York, New York. Chicago businessman Arthur Spiegel, of Spiegel Catalog fame, who brought in his Equitable Pictures, was named President. Selznick was named Vice President and General Manager. All-around showman William A. Brady, a theatre man, was named production manager. Selznick got a contract to distribute the films of Jules Brulatour's Peerless Pictures. World Film then merged with Peerless and together they formed Peerless-World Studio, a name long associated with the Fort Lee film colony. The merged company settled in at the Peerless Studio on Lewis Ave. in Fort Lee with Selznick in charge. In 1915 he hired famous actress Clara Kimball Young away from the Vitagraph Company, Sidney Olcott from Kalem Studios plus the French director Maurice Tourneur away from the American branch of France's Pathé.

Production at the new company was brisk. But, as was Selznick's pattern, he began to bang the Selznick drum loudly. So loudly that he was drowning out World Pictures and its other principals. The New York movie community was beginning to recognize L.J. Selznick as a force in his own right. As an employee of World, Spiegel and the board did not like that.

Goodbye World Films, Hello Selznick Pictures

By 1916 Selznick's antics and shameless Selznickery had irritated the board of World. He was not only a stockholder, but an employee of the company. Officially he was vice president and general Manager but from a practical perspective, he WAS the corporation. He felt his partners and the bankers who financed the company were necessary evils and fodder for his Selznickery. Arthur Spiegel felt differently. He felt that Selznick should be promoting World Films instead of himself. So the board engineered a buyout and fired him, just kicking him to the curb.

Undaunted, Selznick felt confident and took a very Selznickian attitude: If you can't join 'em, beat 'em. He formed Selznick Pictures and took with him World Picture's biggest star, Clara Kimball Young, forming Clara Kimball Young Pictures with him as President. He initially operated from the bar in the Hotel Claridge in New York, but by the beginning of November, he had leased the old Biograph Studio on 175th Street.

Even though left World Pictures, the company he founded, with very little cash in his pocket he had one thing going for him. He was famous and knew how to promote the hell out of himself and his pictures. The film industry and movie patrons across the nation saw Lewis J. Selznick as a much bigger deal than he actually was. In reality, he had very little going for him aside from his chutzpah, which he exploited to the max. Things soon got much, much better for L.J.

Here was his next Selznickian idea:

The only entities that had lit signs advertising movies were the movie theaters themselves. So Selznick defied the norm and built a brightly-lit billboard with "Selznick Pictures" emblazoned across the top. Then brightly lit pictures of Clara below that advertising a picture that did not yet exist, The Common Law. So great was the draw of lit signs at the theaters that confused patrons tried to buy movie tickets at the soda fountain on the ground floor of the building at 46th and Broadway, where the sign hung.

Next, he figured out the budget for shooting and marketing the non-existent film.

Banking on his name recognition, which was greater than most, and that of Clara, the most popular of actresses, Selznick went to the State's Rights market and presold exclusive franchise rights to distribute in key cities and geographical areas. His plan worked. He caught the attention of several prominent exhibitors including Nicholas and Joseph Schenck of the Marcus Lowe chain, Sol Lesser, a young California theater chain owner, and Aaron Jones, and Nathan Ascher, Chicago theater owners. They paid him a premium to have exclusive territorial rights to Clara's first film under the Selznick name. Between the Clara Kimball Young and Lewis J. Selznick names, he raised enough money to produce the film, making his profit on the film rental fees from the franchisees on the backend.

Another bit of original Selznickery he invented was a promotional technique today known as "Throwing a Party." Banking on Selznick's name recognition and flamboyance, he threw elaborate post-production parties at the Astor and Ritz-Carlton Hotels for exhibitors, bankers, the press, and other industry influencers featuring exquisite opulence, and "cut flowers, dancing, food, and the assorted juices of corn and grape." All the big names in New York would attend. These elaborate screening events raised excitement and stirred interest in Selznick, his stars, and their movies.

He successfully reprised the process with Ms. Young and brought big stars of the day into the fold, including Owen Moore, Norma and Constance Talmadge, Alla Nazimova, Richard Barthelmess, and others. His stable of directors included Maurice Tourneur and Herbert Brenon. All were prominent and could be actively promoted in the Selznick way.

Working without a permanent studio, signing actors and directors on a project by project basis, Selznick was producing hit after hit, success after success, building his little company into a force that others had to take notice of. Those others included Carl Laemmel it Universal, and Adolph of Paramount, who would become a rival and later a partner.

He next offered the distributors and exhibitors another new and noel idea: they could book his star-studded features one picture, one star at a time, instead of being forced to buy "programs" that included the bad movies as well as the good. From Selznick, you only got the good stuff and didn't have to take any crappy movies, because he didn't produce any. The star system was well underway.

The Movie Industry Grow Up

He may not have been the wealthiest of the movie men, but he may have certainly been the most famous and easily the most recognizable. He joined other luminaries who began to recognize that movie patrons were beginning to demand more sophisticated movies, with complex plots, longer running times, and bigger stars. They were willing to pay higher ticket prices. It was no longer just working-class escapism. It was a social event and a broader cross-section became what we now call "the movie-going public."

World War I in and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic caused a major shift in the movie business. Many of the early companies were producing "a cheap show for cheap people." Many of them lost a huge percentage of their revenue, and went out of business. These included the biggest of the day: Biograph, Kalem, Lubin, Selig, Edison, American, Essanay, KayBee, and many others. By the end of the 19-teens, the first wave of the silent era was over. The old guard had faded away. The number of companies out of business by 1919 was staggering. However, the second wave in full swing, and many of them would be very successful.

Lewis J. Selznick had joined the new wave of movie industry powerhouses: D.W. Griffith, Adolph Zukor, Jesse L. Lasky, Cecil B. DeMille, Samual Goldwyn, William Fox, Thomas Ince, Mack Sennett, Harry Aitkin, and others. A new wave of high-priced stars was on the horizon: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Lon Chaney, Norma Talmadge, Gloria Swanson, Clara Kimball Young. Demand made stars, which made high salaries, which made high priced tickets. No longer would a nickel get you in. Fifteen cents to twenty-five cents. For the biggest stars in the biggest pictures, you might even pay a couple of bucks.

Selznick joins with...Zukor?

As radical as Selznick was at what he was doing, Adolph Zukor was equally as radical with his business style. Selznick accumulated lights and stars. Zukor accumulated companies, studios, and star contracts...and power. Not because he wanted stuff, but because of the power it represented, the control he gained, the profits it represented. While most early moguls made emotional decisions (including Selznick) Zukor was quite cold and calculating in his decision making. Having things only made sense if they could help move him forward in the accumulation of power and control.

By the late teens, Zukor had six companies and brands, and five studios (four large West Coast plants, and the largest on the East Coast). But more importantly, he controlled the biggest stars and directors in the business-the ones who brought in the most in ticket sales and commanded the highest ticket prices. His had become the largest organization in the business.

The rest of the industry looked at Zukor and his ruthless style with suspicion and derision. He didn't care who he had to step on to achieve his goals. His ego was as big as Selznick's. But where Selznick operated in the face of the industry, Zukor preferred to remain in the background and operate with stealth and anonymity.

Selznick and Zukor fiercely disliked one another. While Selznick never missed an opportunity to jab any of his competitors, he preferred poking a finger at Zukor, in private or, more often, in the press. No one was safe from Selznick'sttacks, but he was a particular thorn in Zukor's side.

So it took the industry by surprise when in August of 1917 it was announced in the press that Zukor and Selznick had combined forces. Zukor offered Selznick a cool half-million for a 50 percent stake in his Selznick Pictures. Zukor lured in Selznick with a promise of peace and prosperity, and a settlement of the war. Selznick would remain as President of the company. As for L.J., he thought he finally had a piece of the Zukor empire. He thought he had Selznicked Zukor.

Select Pictures Corp.

After the allure of the money wore off and Selznick had a chance to think about it, he realized what Zukor had done. Lewis J. Selznick did not own a piece of the Zukor empire. No. Selznick's operation was not merged in with the Zukor family of companies. Instead, Zukor owned half of Selznick's little company, operated separately from all the rest. AND...Selznick had lost the line thing that separated him from all the other movie moguls and motivated him to work hard. The Selznick name was no longer to be on any advertising, on any building, on any film produced under the Select banner. Instead, the name of the company was changed to Select Pictures. Select Pictures was to be above the picture's title, not Selznick. His name would no longer be in public, in lights. He lost his leverage, he lost his fame. He feared nobody would remember who he was.

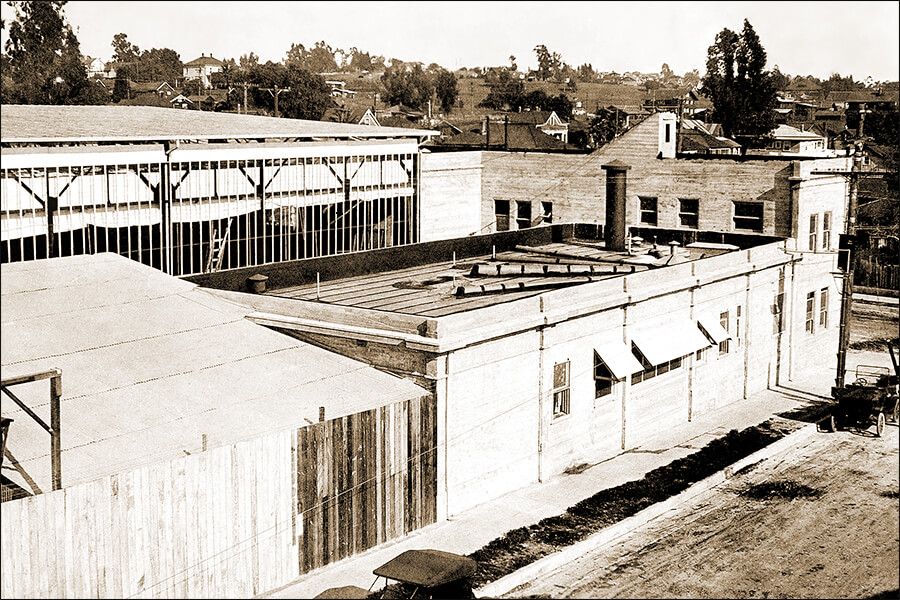

Adding insult to injury, Zukor did not let Selznick set up the new concern at the large state-of-the-art Famous Players-Lasky lot on Vine St., but at the much smaller auxiliary studio a few miles away.

The Whale ate Jonah. Selznick got Zukored.

For two painful years, from 1918-1920, Lewis J. Selznick shot Select Pictures on the Zukor's Pallas Pictures lot in Los Angeles, though Selznick himself remained New York-based. In spite of these things, Selznick prospered financially, the combined movie geniuses of Selznick and Zukor led to success for both. L.J. Selznick was, for this period of his career, a Hollywood producer.

Under their contract, Select was to make a steady stream of mid to low priced fare with lesser-known talent, leaving Zukor's Artcraft and Morosco labels would make the higher quality films with the bigger stars. It was part of Zukor's plan to suppress Selznick who did not know how to operate this way. He was accustomed to working with just a few giant stars making just a few high-profit pictures for each. Zukor wanted the high-end movie market for himself. But almost immediately Selznick began to clamor for bigger stars and bigger pictures, like he had always done before. Zukor didn't like it. As the managing partner Selznick threatened Zukor with another bit of Selznickery, to defy the contract and produce what he wanted to. A finger in Zukor's eye. There was very little Zukor could do. And without his name in lights, Selznick was not happy, and increasingly dissatisfied.

Goodbye Zukor, Hello Selznick Pictures...again.

Meanwhile, in a quiet maneuver, Lewis J. Selznick worked with his eldest son, the 17-year-old Myron, to create a brand new Selznick Pictures. Operating in secrecy, Myron lined up financing and star contracts. The first big-name he attracted was Olive Thomas. Because he was underage, Myron's contracts were all signed, not by him, but by his mother. Myron hung a brightly lit sign above his office at 729 7th Ave. which read "Selznick Pictures-Olive Thomas." The Selznick name was back in lights.

A chip off the old block, Myron began banging the Selznick drum loudly. Adolph Zukor was not pleased. but with other business forces pressing in on him, he was ready to cut the Selznick clan loose. In April of 1919, Zukor made Selznick a buyout offer. Zukor wanted a full million for his 50% stake in the successful Select Pictures, a doubling of his stake. Loathing his relationship with Zukor, Selznick accepted and became Select's sole owner. Selznick and Zukor were glad to be rid of each other. Each had made a considerable sum from the genius of the other. Adolph Zukor hoped Lewis J. Selznick would just fade out of the business. Selznick did not.

L.J. gathered up his players and belonging, and retreated to the comfortable confines of New York and Fort Lee, and ramped up his new Selznick Pictures company. With Myron's help, and Select became the distribution arm of the company with exchanges all over the U.S. and Canada and Selznick Pictures once again started making pictures.

In early 1920 L.J and Selznick Pictures went back to the Peerless-World studio on a long-term lease, and also leased other Fort Lee studios. The Universal, and Paragon Studios also fell into Selznick control.

Selznick was once again a happy man. He was also a determined man. With Myron as the driving force of the resurrected company the Selznick name back in lights. Myron was the firm's President while younger brother, David, took on the V.P. role. L.J. became CEO and the figurehead.

Events went well for the Selznicks. L.J. and sons controlled about 2/3 of Fort Lee's studio space. They put many famous players under contract. Their volume of movies made them one of the biggest forces in the industry.

But the movie industry was moving faster than the Selznicks could keep up. Star contracts were costing more and more causing budgets to skyrocket. A family-owned business just could not keep up with the growing number of Wall Street financed film production businesses and studios. Their luck ran out. In 1923 Selznick Pictures lost many of its stars and was forced to give up its studio holdings. In 1925 they filed for bankruptcy and went out of business.

But they were a resourceful bunch. That was not the end of Selznickery. Myron and David moved to California. Myron Selznick became a famous and powerful talent agent with clients the likes of Katharine Hepburn, William Powell, Vivian Leigh, and Laurence Olivier. David O. Selznick owned a studio of his own and produced Gone With the Wind and King Kong, as well a being a favorite producer of Alfred Hitchcock's, producing many of his best films.

As for Lewis J. Selznick, he never gave up. He was hired to manage another movie business in California, Associated Exhibitors, distributors of low budget pictures. In 1926 they went out of business, and L.J. finally retired.

He lived out his life in his California home with his wife, Florence. Lewis J. Selznick succumbed to a heart attack on January 25, 1933.

He had a good run.