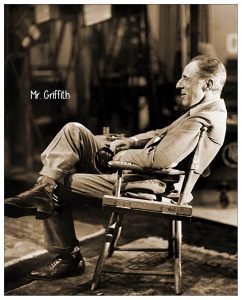

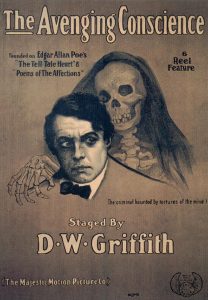

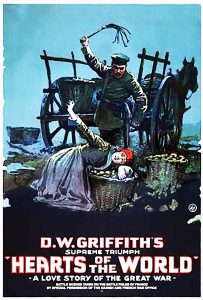

The early industry's greatest film director, D.W. Griffith, called this studio home.

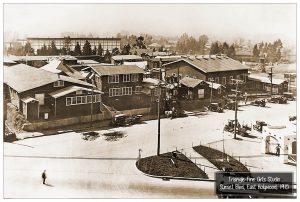

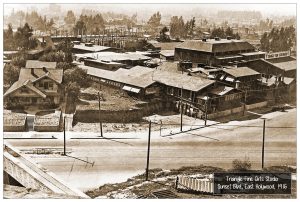

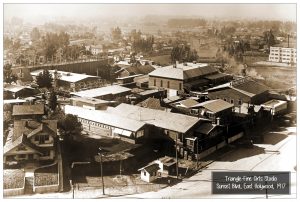

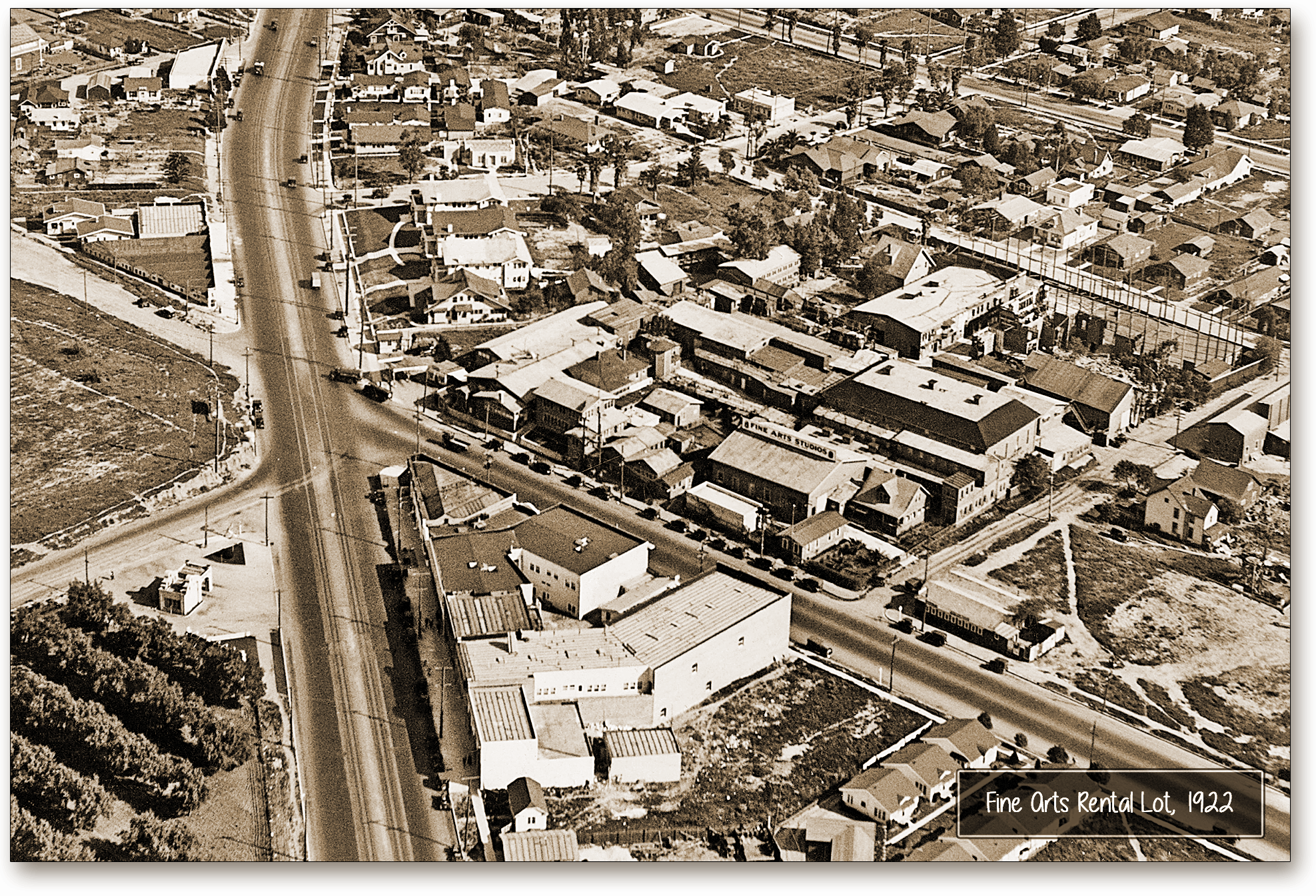

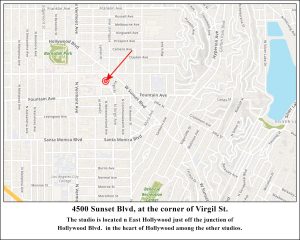

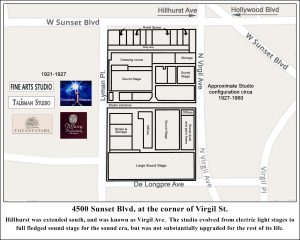

Sunset Blvd. at Virgil Ave.

The studio best known as Reliance-Majestic, Fine Arts, and Tiffany-Stahl.

Seventeen owners in half a century of continuous operation,

the studio lived boldly, died with a whimper, and burned out in one final blaze of glory.

click to enlarge

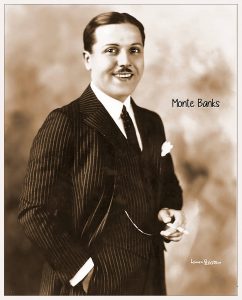

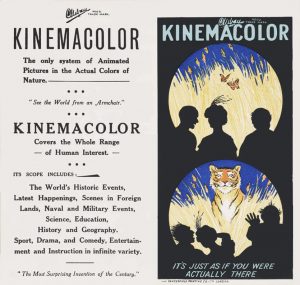

The Founders of the Kinemacolor Process

click each to enlarge

Related Pages:

- Return to Hollywood page

- D.W. Griffith page

- Columbia Pictures main page

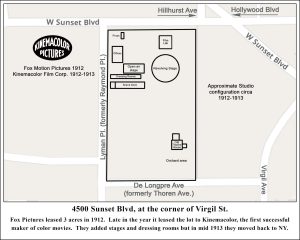

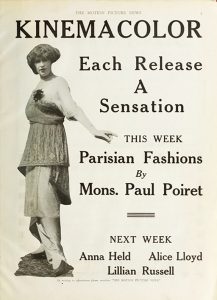

Kinemacolor Studio

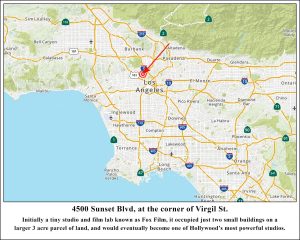

4500-4520 Sunset Blvd.

Company active 1906-1915

Active here 1912-1913

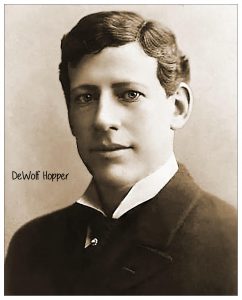

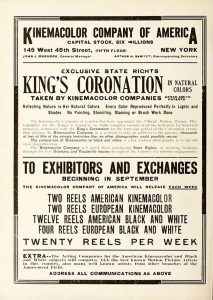

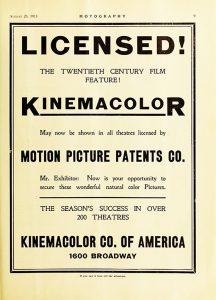

We usually think of color movies coming with The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, but color has been a feature of movies from very early on. In the early 1900s, Kinemacolor was the pioneer of color movies. A British company used its unique patented systems and became the first successful maker of films in color. Kinemacolor was the creation of Charles Urban (the money man) and George Albert Smith (the engineer). Urban, an American ex-pat living in Britain, bought some patents, and Smith, a British native, developed the camera and projector that became known as the Kinemacolor process.

They developed a three-color process whose results were less than satisfactory, so they re-engineered and developed a two-color process whose results were considered spectacular. They produced nearly 350 color movies between 1909 and 1915 under the trade name Natural Colour Kinematograph Co. To view one of their films a theater needed to install one of Kinemacolor's proprietary projection systems, which was provided to theaters without charge. The result was considered remarkable for the day and the got great reviews. Though prolific, Kinemacolor was never very profitable, primarily due to two things. First, the cost of outfitting theaters with projectors was very expensive to the company, and second, their process required twice the frames per second, and it needed separate frames each for the red and the green. The result was that movie required four times the film footage to produce a color moving picture. The costs of production and exhibition proved very expensive. Several of their color movies still exist. You can view one by clicking here.

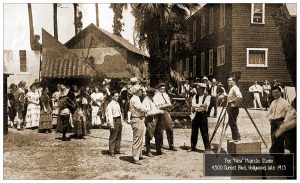

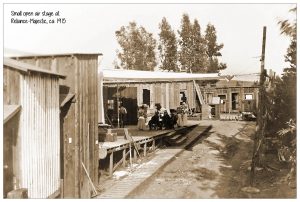

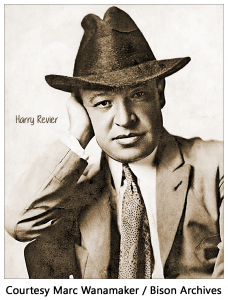

This studio lot started its life in 1912 as Fox Productions (not to be confused with William Fox Films, or 20th Century-Fox). It was a partnership between Harry Revier, L.L. Burns, and others. Revier was a very early low budget exploitation director, never very good and even less successful. L.L. Burns would later found Western Costume Company, which is still Hollywood's largest costume supplier. They used just a part of the three-acre property. There were two small two-story houses. One served as offices and dressing rooms, and the other was their film lab. There was also a small prop building with an outdoor stage in the rear on which they shot crude movies (none of which still exist).

This studio lot started its life in 1912 as Fox Productions (not to be confused with William Fox Films, or 20th Century-Fox). It was a partnership between Harry Revier, L.L. Burns, and others. Revier was a very early low budget exploitation director, never very good and even less successful. L.L. Burns would later found Western Costume Company, which is still Hollywood's largest costume supplier. They used just a part of the three-acre property. There were two small two-story houses. One served as offices and dressing rooms, and the other was their film lab. There was also a small prop building with an outdoor stage in the rear on which they shot crude movies (none of which still exist).

For their color films, Kinemacolor needed bright sunlight year-round. They found what they were looking for in Los Angeles. Under the management of David Miles owners, Charles Urban and George Albert Smith sent the company to take over the Revier and Burns studio and lab at 4500 Sunset Blvd. in East Hollywood. That was November of 1912. They sent 2 companies of players with ambitious plans, leaving another at their large studio on Long Island. They brought 46 actors, crew and office staff from the East Coast.

They leased the small studio from owner Charles Thoren, settling in the pair of two-story cottages. They built a new 50' x 80' scene dock and 19 dressing rooms with hot and cold running water. They also planned to construct homes for all the employees and their families with the aim of making everyone as happy as possible and keep them working long hours.

studio from owner Charles Thoren, settling in the pair of two-story cottages. They built a new 50' x 80' scene dock and 19 dressing rooms with hot and cold running water. They also planned to construct homes for all the employees and their families with the aim of making everyone as happy as possible and keep them working long hours.

Kinemacolor's process required as much light as they could get. To make that happen, they also built a 100-foot diameter revolving stage so they could maximize direct light by keeping the scene directly in front of the sun. The plan was to turn out 6 short one-reel and two-reel movies a week.

Plans included building a huge open-air stage on the back end of the lot but those plans were aborted. Technical problems kept them from producing enough film to justify their huge expenses, and with the untimely death of the president of Kinemacolor of America, by June of 1913 the entire staff was laid off and looking for new jobs. The company packed its belongings and retreated to New York. Their stay was a mere 6 months. Two years later, Kinemacolor was out of business, but for a brief while, Kinemacolor was a big deal. A very big deal.

The Studio known by many names

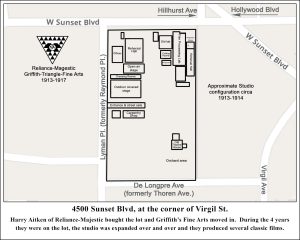

Reliance-Majestic

Fine Arts-Griffith

4516 Sunset Blvd.

Active 1913-1917

Oh, what a convoluted complex of companies!

Mutual. Majestic. Reliance. Triangle. Fine Arts. Griffith.

See if you can follow it.

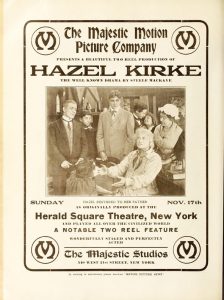

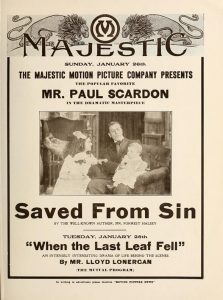

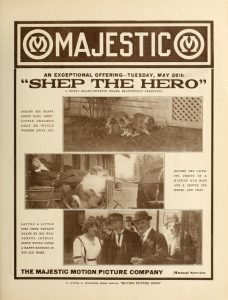

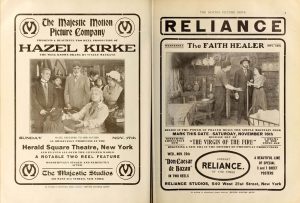

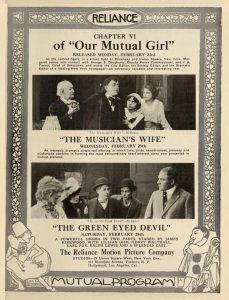

The Majestic Motion Picture Company was incorporated in 1911, the incorporation papers were signed by Thomas D. Cochrane who was the corporate Vice President. Harry E. Aitken was the corporate President and the company was capitalized with $60,000.

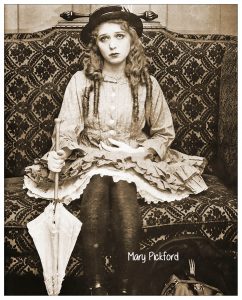

Majestic signed star Mary Pickford stealing her from the much larger Biograph Company and placed her under contract. At that time she was known by the screen name "Little Mary," and was the most popular screen star of the day. Stealing her from the Biograph was certainly a coup and was enough to immediately put Majestic on the map. That enabled Aitken and Cochrane to quickly grow their little company. By mid-1912 Aitken bought out Cochrane and totally controlled the company.

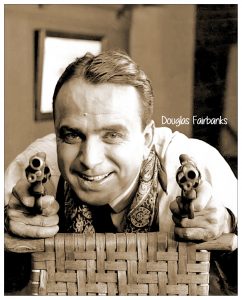

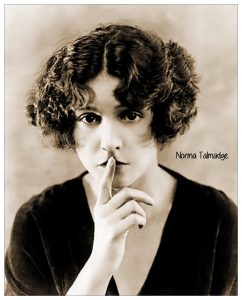

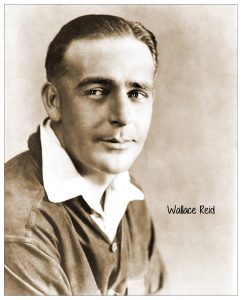

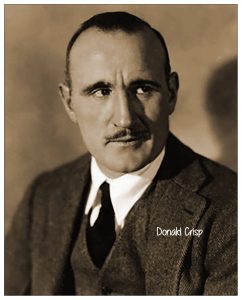

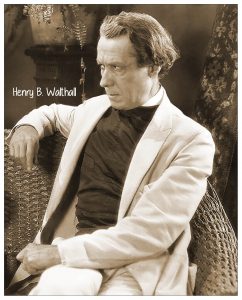

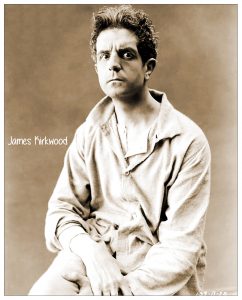

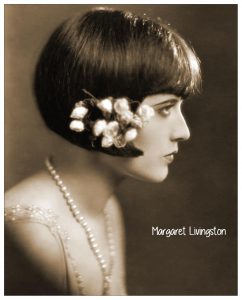

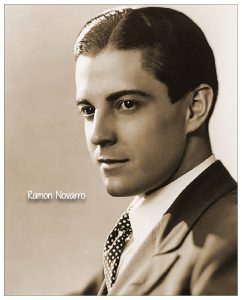

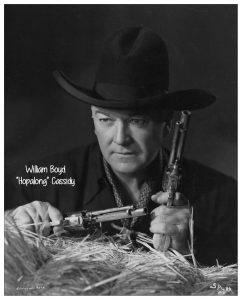

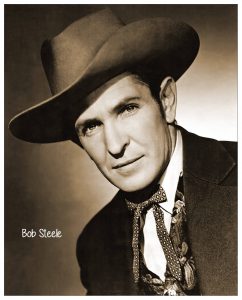

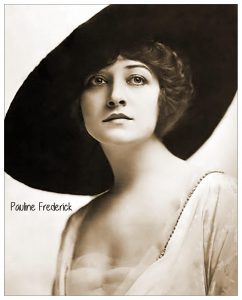

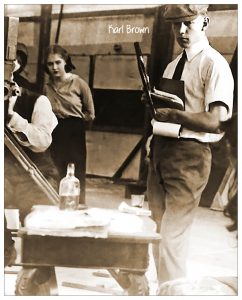

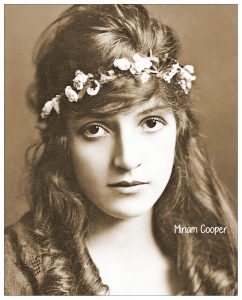

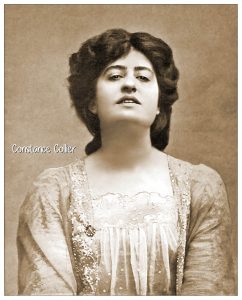

click each to enlarge

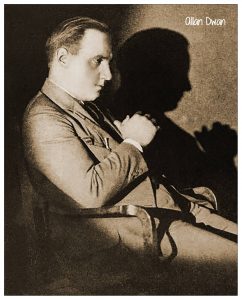

Griffith's Key Personnel

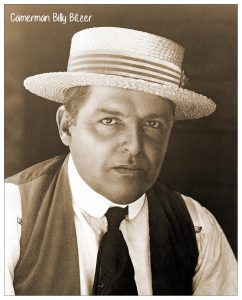

During the period Griffith worked at the Sunset and Virgil studio, two people play key  roles in assisting Griffith, particularly on the two blockbusters, The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.

roles in assisting Griffith, particularly on the two blockbusters, The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance.

G.W. "Billy" Bitzer was Griffith's cameraman and cinematographer all through Griffith's career. They were colleagues at American Biograph, where he collaborated with Griffith in the latter's first attempt at directing. He helped Griffith create the "language" of film. Together they created the closeup, the fade-out, the pan shot, the zoom shot, the crane shot, soft focus, rising, and many more. Bitzer was with Griffith from his directorial debut through the end of the silent era. Together they made 491 movies.

Frank E. Woods like Bitzer, met Griffith when they both worked at the Biograph Company. Their collaborations began in 1908 Woods had been a film critic and scenario writer (what we now call screenwriter). He wrote or cowrote 53 films for Griffith including the seminal The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, and another Griffith masterpiece, Judith of Bethulia. He rose to be Griffith's production supervisor. Their association ended in 1917 when Griffith ended his connection with Harry Aitken, Griffith left for New York while Woods stayed in Hollywood and worked for other companies. Woods was also one of the 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Triangle: The birth of another company.

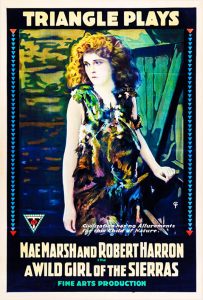

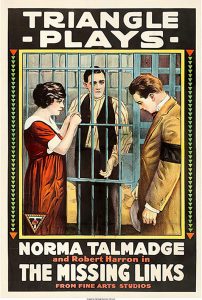

Growing dissatisfaction with how Mutual was distributing their films, Griffith and Aitken teamed up with other industry heavyweight producer/directors Thomas Ince and Mack Sennett plus other partners producers Charles O. Baumann and Admam Kessel of the New York Motion Picture Company (aka KayBee Company). The firm, Triangle Film Company, was created to give them all more control of their films and a better distribution arm for their films. The three points of the "Triangle" referred to D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett, and Thomas Ince. It also referred to the triangular shape of the studio that the company built in Culver City for the use of Ince (Griffith and Sennett already having s.

Because of his involvement in Triangle, Aitken was replaced as the president of Mutual.

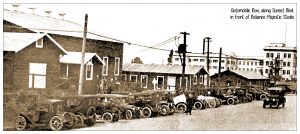

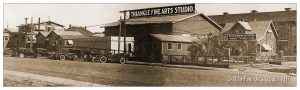

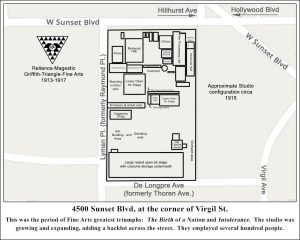

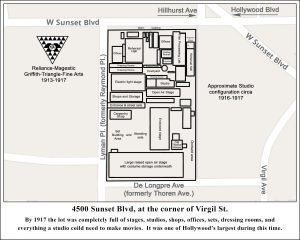

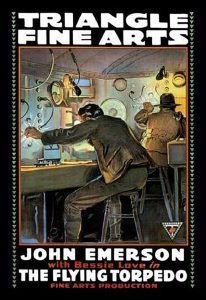

The lot is renamed Triangle-Fine Arts.

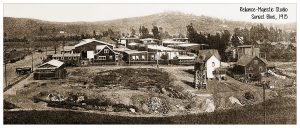

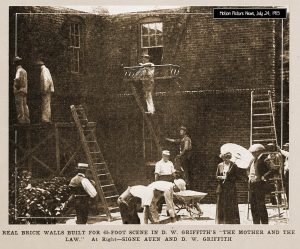

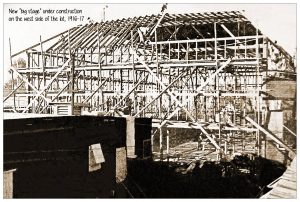

By mid-1915 the studio had become completely owned by Triangle Film Company. They erected a new "Triangle-Fine Arts" sign over the administration building in 1916 and in early 1917 a "huge" new "electric stage" was built on the west side of the lot. The old electric stage was enlarged. The "factory" was enlarged so more film footage could be processed and a new building erected where the release prints were assembled and inspected before shipping to the distributor.

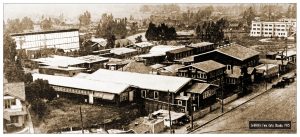

At three acres, during this period of great output, the studio, could support 10 productions simultaneously. Triangle-Fine Arts was one of the largest and most productive studios in Hollywood and the country.

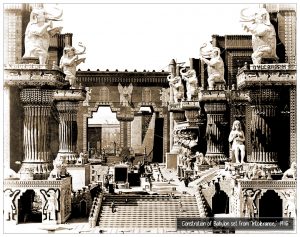

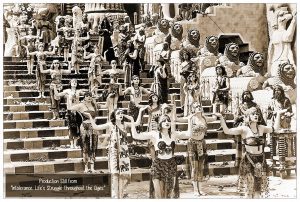

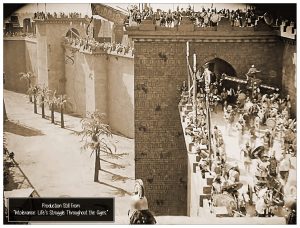

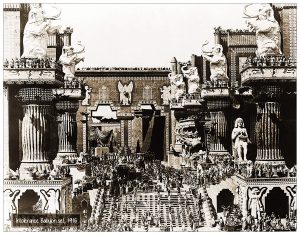

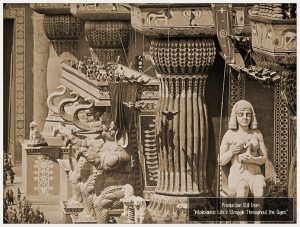

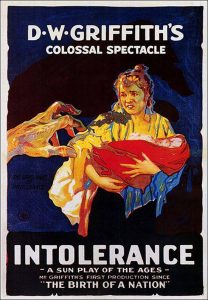

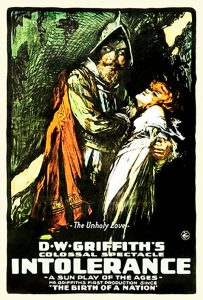

Griffith's next great film, Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages.

Intolerance was Griffith's response to the criticism he took over the glorification of the KKK and underlying racism found in The Birth of a Nation. He always maintained this was not his intent, it was just a story. Intolerance was his apology and was critically acclaimed. It did well at the box office, but was not as nearly profitable as the earlier film, as the expenses for Intolerance were extremely high. It does stand as a masterpiece, in many ways even more so than The Birth of a Nation.

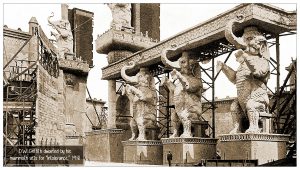

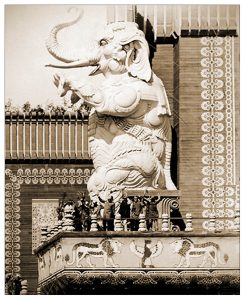

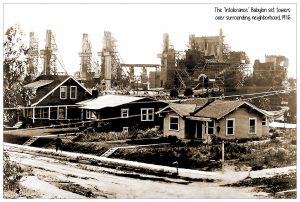

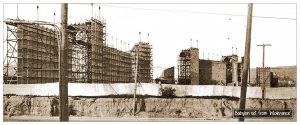

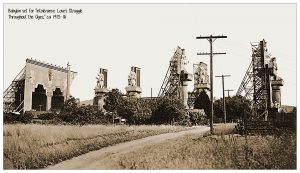

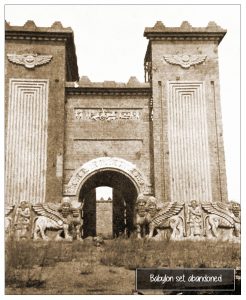

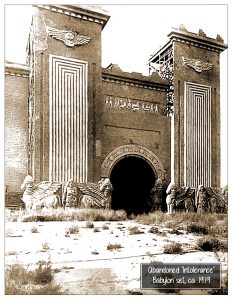

The company had leased a huge piece of land across the street, in an open field, to use as a backlot. It was here that Griffith built his legendary Babylon sets for Intolerance. The sets, which ran along Sunset Drive just off Hollywood Blvd., were like nothing Hollywood had ever seen. However, it was just a few years later when Griffith's protege, Douglas Fairbanks, would build sets of his own that would challenge Griffith's in grandeur, as would those of rival Cecil B. DeMille.

The film was released in 1916 and the sets stood towering over Hollywood until 1919.

In early 1912 Harry Aitken, along with additional investors, formed another company, Mutual Film Company, to distribute the films of Atiken's Majestic, as well as the production companies owned by Mutual's partners, including American Film Manufacturing out of Chicago and Santa Barbara. Mutual placed Charles Chaplin, an up and coming star, under contract and leased a small studio in Edendale to produce his very popular Mutual Shorts.

In early 1914 Aitken formed another production company, the Reliance Motion Picture Company (incorporating in New York with $100,000 of capital). By now he owned or had an interest in about half a dozen companies and studios, including buying this studio lot in Hollywood.

Aitken moved Majestic from a small studio at 651 Fairview, east of town, onto the lot in late 1913. Reliance followed in early 1914. He called the lot Reliance-Majestic Studios. He kept his New York studios.

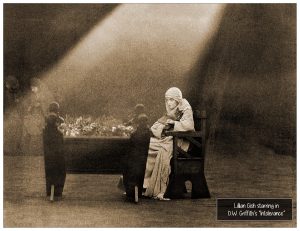

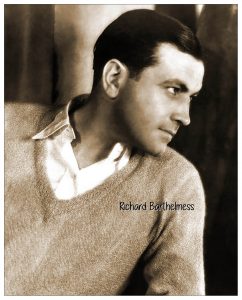

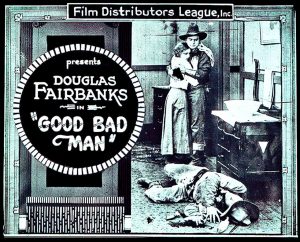

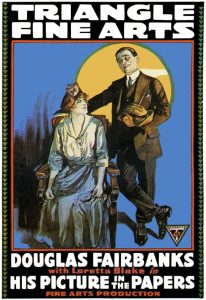

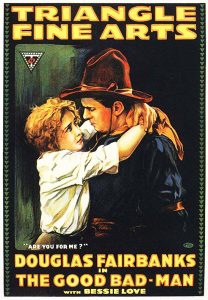

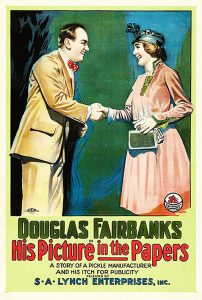

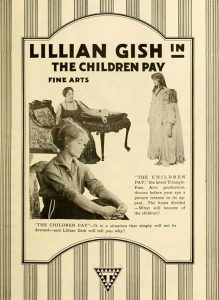

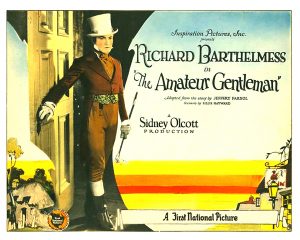

The Growth of the Studio

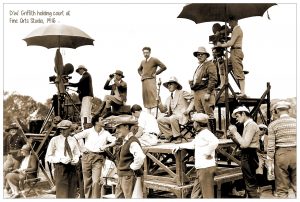

In 1915 an expansion and remodel began in earnest preparing for the arrival of D.W. Griffith, the eminent director, who was to become the "Director-General" of the studio and all of its resident companies. Partnering with Griffith was another coup for Aitken. He followed that with placing newcomer Douglas Fairbank under contract, who rose to fame working on the Reliance-Majestic lot. Griffith brought his stable of contract players, which included Lillian and Dorothy Gish and Richard Barthelmess, all established stars. Aitken was establishing himself as a big force in the business. Or rather was buying himself a place in the industry.

D.W. Griffith was not only established and famous but was considered the premier director in the country by the time he arrived at the Reliance-Majestic studio. He got his start with the Biograph company as a bit player and quickly was recognized for his natural ability to direct. It was not long before he became Biograph's (and the nation's) leading director. In 1911 he moved his Biograph filming unit to Los Angeles and establish one of L.A.'s first studios. After leaving Biograph, he formed his own company, Fine Arts, and was hired by Aitken to run his new Hollywood studio. Griffith brought with him his company of players, technicians, and staff all under personal contract to him.

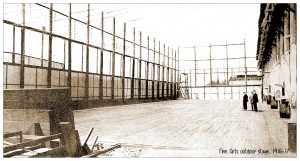

By early 1915 Aitken filled out his three acres, growing to 15,000 square feet of stage production space with the building of "two monster open-air stages" (one 60' x 100' and the other 70' x 190') and a brand new "electric light studio" (60' x 60' 20' high), bringing to 5 the number stages that could be lit. Additionally, he built more than 100 dressing rooms, and a new "factory" which included buildings for printing, developing, washing, drying, and cutting negatives and positives. Reliance-Majestic Studio was considered one of Hollywood's largest studios.

Griffith's masterpiece and the formation of Triangle.

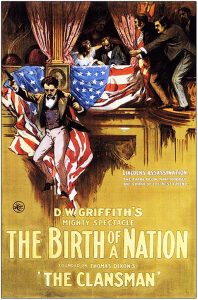

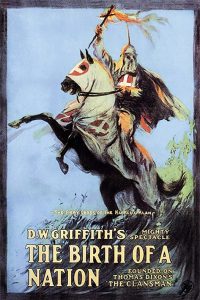

During this time Griffith produced one of his masterpieces, The Birth of a Nation. It was critically acclaimed and made a lot of money for Griffith, Aitken, and other investors, including theater owner William H. Clune. However, it was not without much controversy (read more about this here).

From Thomas Dixon's famous book, The Clansman, Kinemacolor already shot considerable footage on a fly-by-night basis across the South, but the picture went way over budget and they had little usable footage to show for it. Aitken and Griffith stepped in (planning to shoot in Kinemacolor) and arranged with Dixon to buy the rights and take over production. After seeing what Kinemacolor had shot, they scrapped it, and the idea of shooting in color, and began a fresh production.

The Birth of a Nation was originally intended to be a Mutual release but its board of directors did not want to put up the money, thinking it would never make a profit. They thought is it a bad investment. So, Griffith talked Aitken into partnering up and Aitken agreed to finance the project. They formed a one-picture company, Epoch Pictures, to produce and release the film.

They proved Mutual wrong. Thye made a lot of money for themselves and their investors. The Birth of a Nation was the highest-grossing film of the entire silent era.

click to enlarge

The Griffith-Aitken relationship ends, and Triangle folds.

A true artist, D.W. Griffith was never satisfied, always restless. In March, 1917 Griffith ended his relationship with Triangle, Fine Arts, and Harry Aitken. The reasons reported in the press were a little confusing. Griffith said it was purely business, but rumors persisted that there were some underlying animosities. I believe that Griffith did not like the constraints that Aitken, his budgets, and Triangle placed on him.

Griffith's company, players and staff, left the studio in March of 1917, shortly after Griffith. His resignation ended any contracts the others may have had with Aitkin, Triangle, and Fine Arts, as they were under personal contract to Griffith himself. As a continued owner of the lot, Griffith continued to make films there under his personal brand.

At the beginning of April Aitken asked Ince to step in and take over the remaining contracts and productions, and moved them to his studio in Culver City. However, the writing was on the wall for Fine Arts, Triangle, and Aitken. Even Ince and Sennett were not long for the organization and sold their interests, Sennett left the company in June-July of 1917, and Ince a month later, in August. Adolph Zukor bought the remaining assets but the company folded in 1919. All the Triangle owners, except Aitken, would go on to do great things and make great movies.

In 1919 Griffith moved his company to Mamaroneck, NY where he bought an old estate and built a large studio where he produced several more legendary films.

Photoplay Magazine July, 1917: “Fine Arts has definitely passed into film history, with its former name, Reliance-Majestic and the great Griffith organization…now deserted save for a lonely watchman.”

The Hugest Sets in Hollywood

From the time construction began in 1915 until the sets finally came down in 1919, D.W. Griffith's monumental sets for his masterpiece, Intolerance, towered over the junction of Hollywood and Sunset Boulevards. They were the biggest and granted sets the industry had ever seen and reigned as such until Cecil B. DeMille and Douglas Fairbanks created their own towering sets. But Griffith's Babylon set will always be the one people will regard as the biggest and best Hollywood ever produced. The sheer scope was breathtaking. It was a landmark in scenic design.

A Gallery of Intolerance Photos

click any to start slide show

Is There Life After Griffith?

The studio did not stay closed for long. A matter of months. As one of Hollywood's premier studios, it had plenty of life left. It re-emerged as a rental studio. Dozens of companies, stars, directors, and producers passed through its stages throughout the years. Even Griffith continued to make his films here as a tenant. The studio thrived another 4 decades beyond the years of Griffith's heyday.

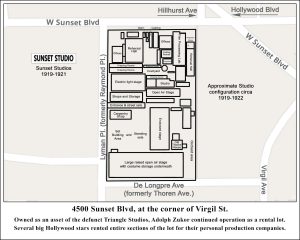

Adolph Zukor (the owner of Paramount) bought Triangle's assets, and the Fine Arts Studio was among those. The studio was not closed for long. By mid-1917 all Triangle personnel had left the lot and H.O. Davis was hired away from Universal to manage the studio as a rental facility. He began to aggressively pursue producers to rent all or part of the studio.

4500 Sunset Blvd.

Active 1918-1921

In July 1918 the studio was renamed Sunset Studios, though still under the ownership of Triangle and Adolph Zukor. It became a popular place for stars to shoot personal films, as a rental lot for smaller independent companies, as well as overflow production space for other studios. There were many stars who received their fan mail at 4500 Sunset Blvd., the studio's address. Even Griffith returned to shoot films for his new distribution deal with Artcraft/Paramount (Lasky and Zukor).

Initially, it was subdivided into several smaller, complete studios. Each mini-studio had everything it needed to be a completely functional studio. By 1919 there were several major stars who each occupied their own small studio within the larger studio.

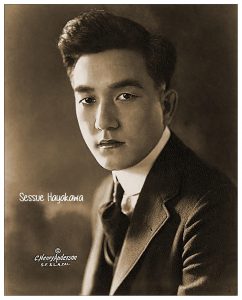

Sessue Hayakawa's Haworth Pictures Corporation

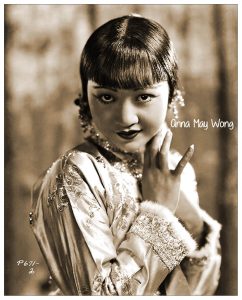

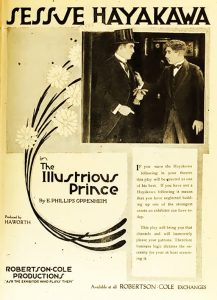

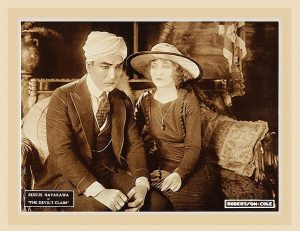

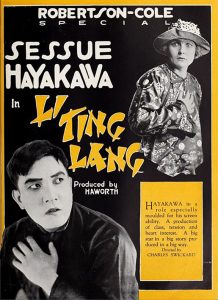

Sessue Hayakawa was a huge star. He was the first Asian to gain national stardom (followed by Anna May Wong). Hayakawa, who made more money than most stars, was known for playing the poor Oriental man who would fall in love with a white woman, but was always cheated of his love by an intervening white man. During the silent era, his career was based on this premise, and the good looking young man rose to sex symbol status.

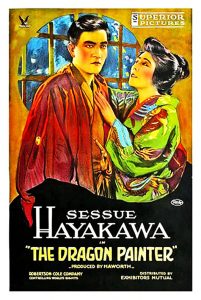

Along with his business partner, William Worthington, and general manager Francis J. Hawkins, Hayakawa moved the company into one of the mini studios in February of 1918 and began aggressively making feature films, which proved immensely popular. Notably, he made The Tong Man and The Dragon Painter, both directed by his partner, William Worthington.

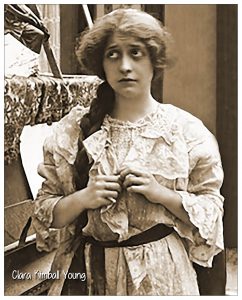

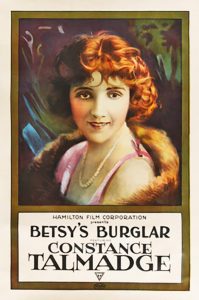

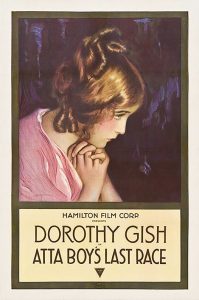

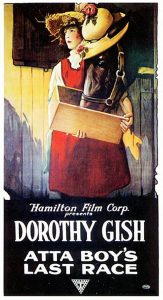

Clara Kimball Young and Dorothy Gish

In September of 1918 Clara Kimball Young, a major star of the day became the tenant of one of the mini studios. Her Garson Productions would soon move into its own full studio in Edendale in 1919. In November, Dorothy Gish, sister of the great star, Lillian Gish, rented another mini studio until her rental space was complete at the Lasky Studio. Both used their studio-within-a-studio to produce several films.

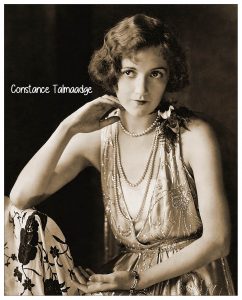

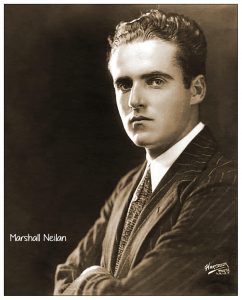

Mary Pickford and Marshall Neilan

During this period, "Little Mary" and director Marshall Neilan moved their companies onto the lot where they collaborated on Pickford's Daddy Longlegs. While there, each produced pictures independent of one another. Pickford went on to own her own studio in 1919 and become a founding partner in United Artists and with husband Douglas Fairbanks, would buy a large studio on Santa Monica Blvd. Neilan would go on to a long directorial career and would own a studio in Edendale a few years later.

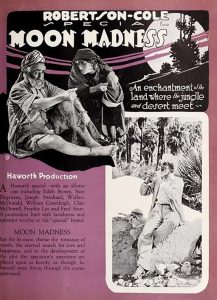

Robertson-Cole on the lot.

The studio that would later become famous as RKO and would eventually be absorbed into the Paramount studio started its life in 1919 as Robertson-Cole Studio. No sooner had they completed it then R-C (as it was known) needed more space. So they signed a lease with Triangle's Sunset Studios to lease the entire lot where their big star, Sessue Hayakawa (and his Hayworth Company), was already ensconced, and so R-C could have already badly needed overflow space.

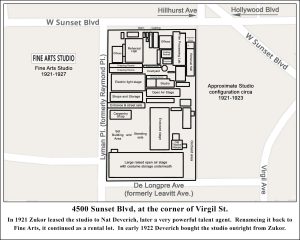

The Return of the Fine Arts Name

Fine Arts Studio

Active 1921-1927

For a brief time during 1921, the studio was called Independent and was advertised as a rental lot, but by the middle of 1921, Nat Deverich took out a master lease on the old studio. Deverich had been a contract player with D.W. Griffith and Reliance-Majestic (as was his wife, Loretta). Later he would become a very powerful talent agent with clients such as James Stewart, Myrna Loy, Kathryn Hepburn, and many, many more of the rich and famous.

When he took over the lot, he renamed it back to Find Arts, incorporating as Fine Arts Film Company (similar name, different company). He decided that, as an established and recognizable name, he could fill his studio with productions. He was right, and was able to quickly rent out the stages and offices. One of his first tenant was Texas Guinan, who produced a series of 12 western and northwestern dramas.

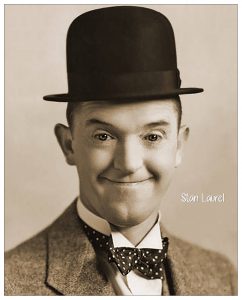

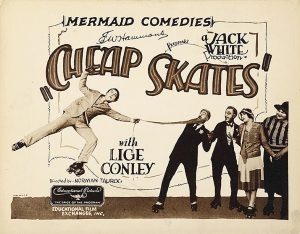

Deverich directed features of his own while actively pursuing independent producers, traveling around necessary looking for tenants. One of his early renters was famous cowboy star (and former owner of Essanay Film Manufacturing Company), G.W. "Broncho Billy" Anderson, who produced several films at Fine Arts. In mid-1923 the entire Fine Arts lot was leased by Educational Pictures. Under the Educational's production manager E.H. Allen, they produced their comedy series, Jack White Comedies and Lloyd Hamilton Comedies, Mermaid Comedies, and Cameo Comedies. Educational invested $90,000 in renovations and by September they were ready to start production.

Educational was ambitious in their production schedule, running 11 comedies units, leasing two complete studios, here at Fine Arts, and the old Chrisite Studio at Sunset and Gower. It was only a matter of time before Educational would need its own studio, and in 1924 they bought the old King Vidor studio on Sunset Blvd. next door to Pickford-Fairbanks on Santa Monica Blvd.

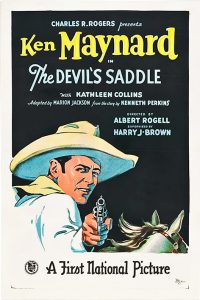

Even after Educational left the lot, Fine Arts carried on a rigorous schedule of stage and facility rental to half a dozen or more productions at a time. In 1926, First National leased several studios, including Fine Arts, while their new studio was being constructed in Burbank.

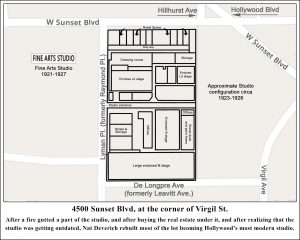

Later that same year Deverich bought the last acre and a half of the three the studio sat on. He now owned the full three acres. Again, he did a considerable reconstruction of the studio including building a new stage that measures 275 feet by 95 feet. The studio now had 4 enclosed "dark" stages, including the largest in Hollywood at the time. Fine Arts had become the most modern studio of the day.

In January of 1922, what was left of the old Triangle company sold its interest in the lot to Deverich for $100,000. The studio was in fine shape, but Deverich decided on some upgrades anyway, so after a fire burned down the film lab in January 1923 he invested another $250,000, tearing down many of the old Reliance-Majestic era wooden structures and erecting new, modern buildings, to carry him into the future. He added storefronts along Sunset Blvd. to lease to retail tenants.

Another Big Change of Ownership

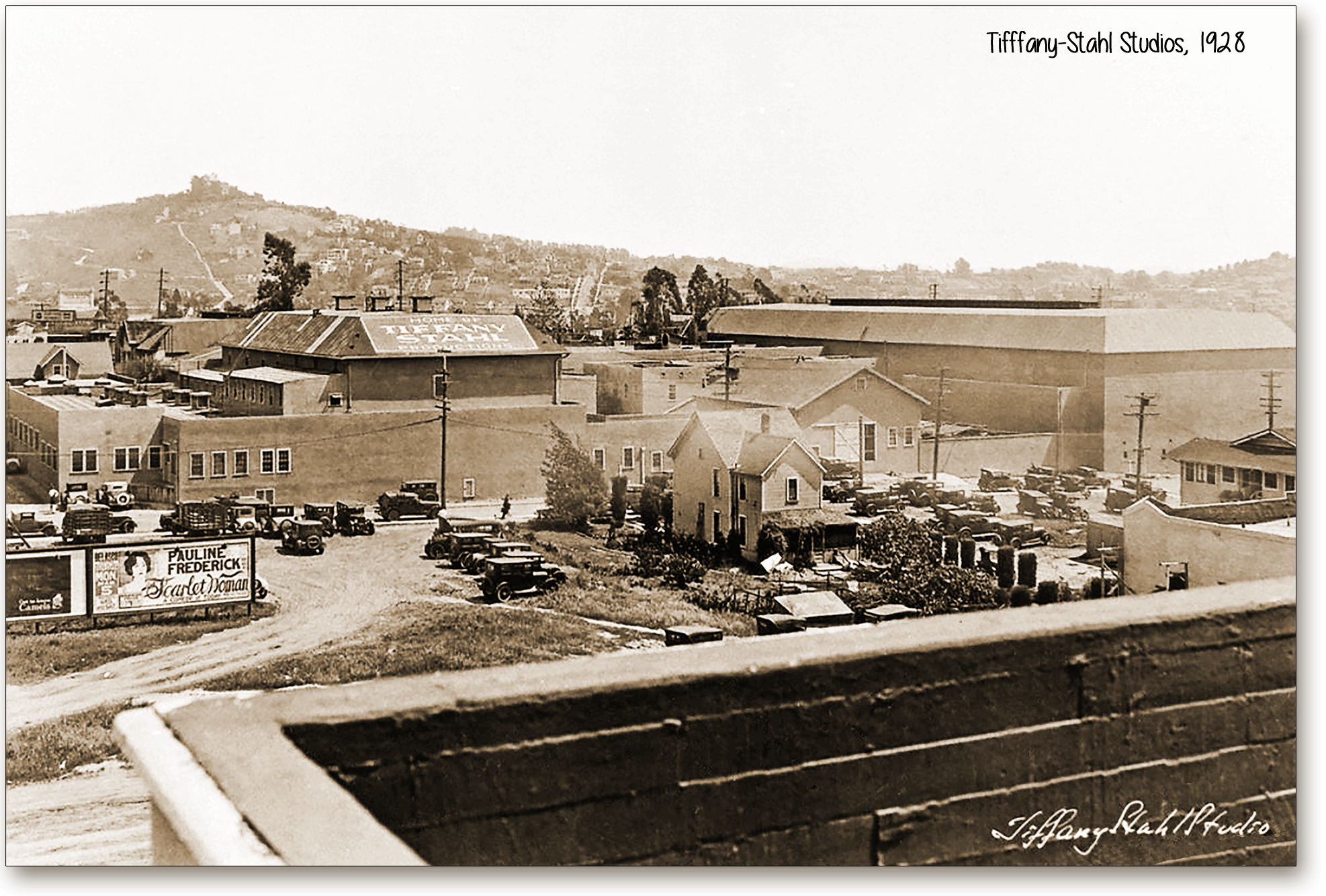

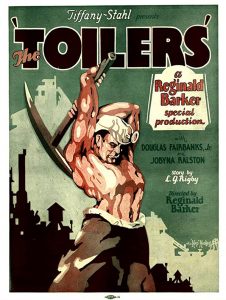

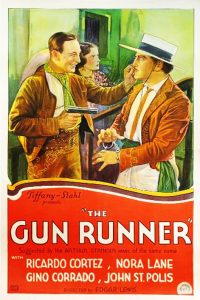

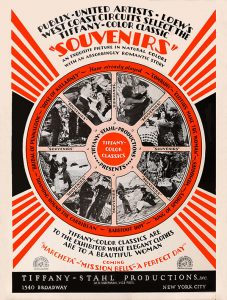

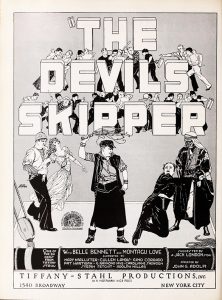

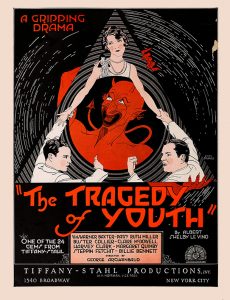

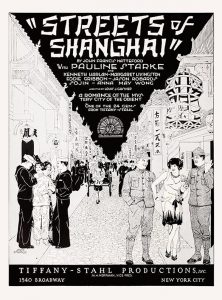

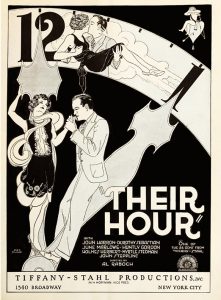

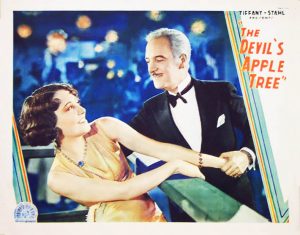

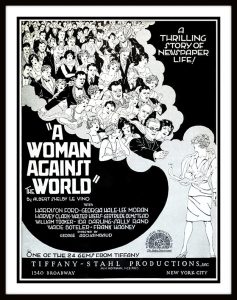

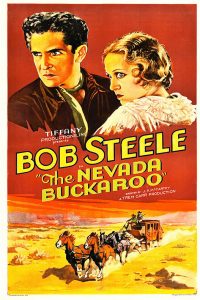

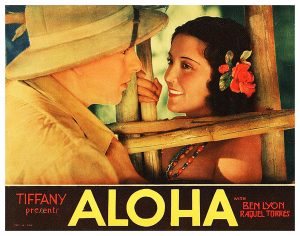

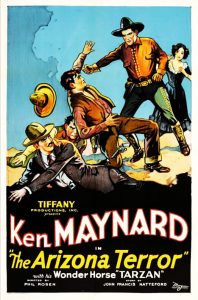

Tiffany Productions

Tiffany-Stahl Productions

Tiffany / Tiffany-Stahl Studios

Company Active 1921-1932

Active here 1926-1932

As Tiffany-Stahl 1927-1930

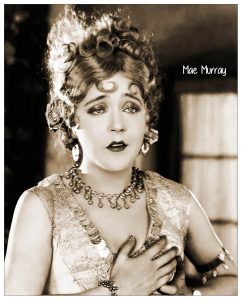

Mae Murray was an up and coming star with The Lasky Company at the time she met her husband, Robert Z. Leonard in 1918. She was dubbed "The Girl with the Bee Stung Lips." A quick look at her photos and you will realize why. It was her fashion statement.

Miss Murray and Mr. Leonard, along with partner Maurice H. Hoffman, formed Tiffany Productions in 1921, an independent production company. Leonard was known for producing low budget "escapist" entertainment of little artistic value. Even though his films rarely lost money, it was hoped that with Murray's star power, they could elevate their company to compete with the larger companies. From 1921-25 they put out only 8 films shooting at Metro in New York and Goldwyn in Culver City.

In 1925 the couple divorced and sold their interest in Tiffany to L..A. Young. The company ramped up production producing some 70 movies over the next two years, and in 1926 they decided it was time for a studio base for their company. They leased the recently vacant Fine Arts studio from Nat Deverich.

Still, they did not have the right formula for success and the company struggled to find its place.  So, in mid-1927 they set off in a new direction, abandoning their "state's rights" approach to distribution and open a chain of 28 of their own exchanges to directly distribute their films to the better theaters. Then, to continue the move upward, in November of the same year, the company approached John M. Stahl, a well-known producer and director making prestige pictures at MGM. Young and Hoffman offered him an equal partnership. Perhaps he could raise the quality of the Tiffany product and bring a little class to the Tiffany name. The company and studio were renamed Tiffany-Stahl.

So, in mid-1927 they set off in a new direction, abandoning their "state's rights" approach to distribution and open a chain of 28 of their own exchanges to directly distribute their films to the better theaters. Then, to continue the move upward, in November of the same year, the company approached John M. Stahl, a well-known producer and director making prestige pictures at MGM. Young and Hoffman offered him an equal partnership. Perhaps he could raise the quality of the Tiffany product and bring a little class to the Tiffany name. The company and studio were renamed Tiffany-Stahl.

The new Tiffany-Stahl bought the Fine Arts studio and the property from Deverich form $500,000 and did another $250,000 in improvements, and set out to make some movies.

John Stahl took charge of production, with all producers, directors, and writers reporting directly to him. He was largely successful, and brought Tiffany out of the stigma of low budget, poverty row production.

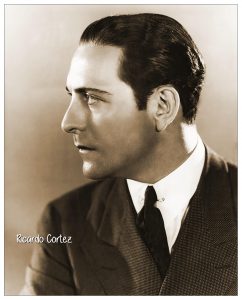

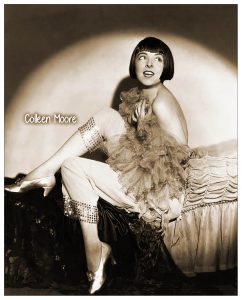

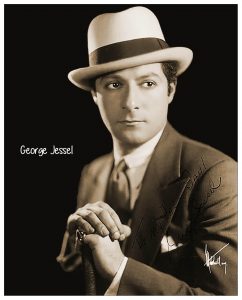

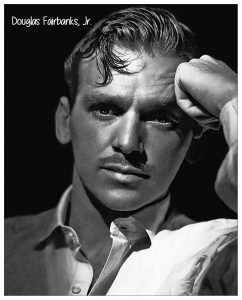

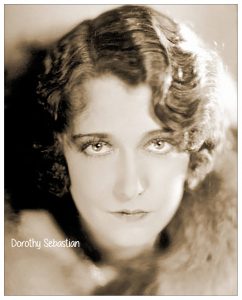

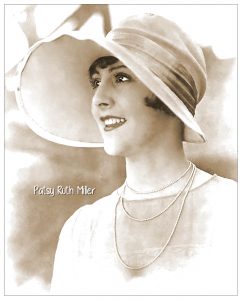

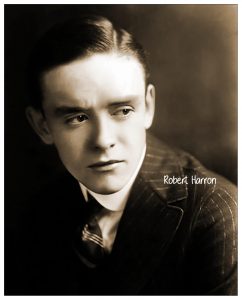

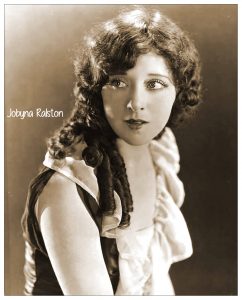

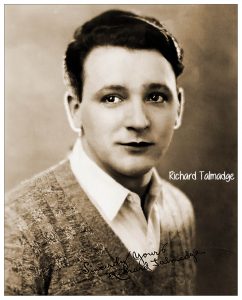

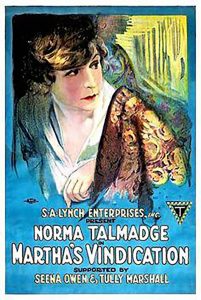

In 1927 and 1928 John Stahl began to make sweeping changes to the studio plant and the company's operations. He retooled the studio for sound and color production. He immediately began to gather players, directors, and writers. The four silent stages were rebuilt as sound stages, and he leased RCA's synchronized sound system, calling it Tiffany-Tone. He signed stars Ricardo Cortez, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Carmel Myers, Jobyna Ralston, and Richard Talmadge, George Jessel, Sally O'Neill, and Dorothy Sebastian, among others.

They were ready to compete in the new talkie market and compete head to head with the big players.

At the end of 1928, the studio announced its presence to all aviators by painting "Tiffany-Stahl Studio" in big bold letters across the top of the big stage.

1929 and 1930 were particularly bad years for Tiffany-Stahl. It began with Hoffman, the driving force behind Tiffany, leaving the company and selling his interests to Young. And, In spite of John Stahl's efforts, business problems persisted. They were behind schedule in delivering promised pictures to the theaters, and theater owners began to resent the Tiffany's deceptions. They would deliver an old movie under a new name causing theater patrons to ask for a refund. This was done as they prepared to reshoot silent movies for sound. As a result, theaters began to refuse Tiffany pictures as they were not the pictures advertised. They also delivered "talkies" with less dialog than their contracts called for. This rift between Tiffany-Stahl and the theaters owners lasted for more than half the year. (Ed. Though I have no direct evidence, I suspect that John Stall, hired to raise the company's image, began to tire of not getting the full backing of the upper management in his efforts to deliver promised quality fare, and was not willing to put up with the wrath of the exhibitors).

Mae Murray filed a lawsuit in 1930 for damages to her reputation. Tiffany Jewelers sued for trademark infringement. Twickenham Studios in Great Britain sued over unpaid bills. And, as the nail in the coffin, John Stahl left Tiffany to go to work for MGM.

Tiffany needed a new direction.

In an attempt to recover and restore its place in the industry, L.A. Young announced big structural changes. In the end, the restructuring actually became a merger with Educational Pictures, its larger competitor, with Young becoming an Educational board member and remaining in charge of the Tiffany unit with the new name California Tiffany based on the Tiffany lot.

The studio was once again available to rent.

Talisman Studio

Active 1933-1943

With a bang of an announcement, the new owners of the studio advertised in trade papers:

“Talisman Studios Corporation wishes to announce that they have taken over the properties of the Tiffany Studios and are now prepared to lease studio space, RCA Sound, Cameras, Lights, and all other Production Facilities. Talisman Studios Corporation 4516 Sunset Boulevard.”

Several Eastern bankers had signed a master lease with Tiffany's L.A. Young, who still owned the lot, and renamed it Talisman Studio. The intention was to produce a block of 20 pictures. Very soon, however, they ran into financial trouble, and Young was forced to repossess the studio and, once again, run it as a rental studio. Business associates of Young incorporated a new Talisman name and leased it (and other Tiffany assets) back from Young. L.A. Young, while out of the movie production business, found himself back in the studio rental business.

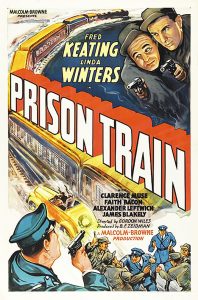

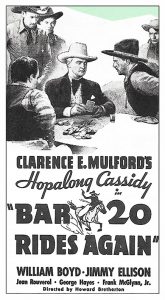

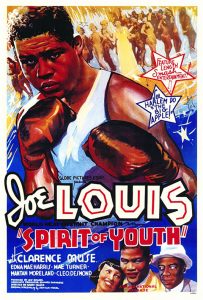

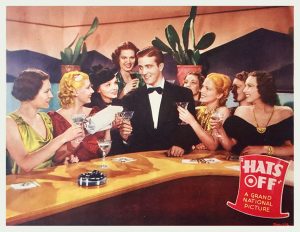

Talisman had a number of major tenants. One of the largest was Monogram Pictures, who leased the studio in 1936 until they bought their permanent home a few blocks away in 1942. Monogram was a fabled low budget "poverty row" producer who also owned a movie ranch in Calabassas which, today, is known as Melody Ranch. Republic and Pathe also leased space on the lot, as well as dozens of small production companies needing inexpensive stage and office space. It became a popular place for low budget production.

In 1943 PRC (Producers Releasing Corp.) move onto the lot in anticipation of buying it. They made a bid of $250,000 at auction, but Columbia swooped in and outbid them with a $300k bid.to buy the old studio. As a consultation prize, PRC bought the old Educational studio on Santa Monica Blvd. and Columbia moved in and started shooting.

Columbia Studios Sunset Annex

1943-1961

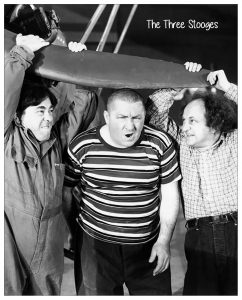

The growing major studio, Columbia Pictures, began acquiring space across Hollywood after filling up their main lot further west on Sunset Blvd., and in 1947 bought Talisman when again they ran low on stage space. They made good use of it, basing their Three Stooges comedy unit at the newly acquired studio. The Stooges were Columbia's big moneymaker.

For a while, Columbia was forced to share the studio with tenants already under lease: Monogram and PRC, but by 1944 had the studio all to itself. Monogram had planned a remodel of the lot, but instead bought the old Charles Ray studio a few blocks away.

By 1949 Columbia no longer needed all the space, and, once again, the studio was available for renting out. Calling it Sunset Studios, Columbia ran it as a rental lot until 1960 when it was bought by a real estate developer.

In 1961 Variety wrote: "The old Griffith Studio sold For Supermarket. One of Hollywood’s historic landmarks, D.W. Griffith’s old Fine Arts Studios where he filmed “Intolerance”, is to be razed for the now-projected construction of a supermarket. Columbia Pictures, which as owned the studio erected around 1913 and operated it under the tag of its SUNSET STUDIOS, has sold the property to Appea Development Co. and Larry Slaten for $900,000. Proviso in deal provides that Columbia continues to occupying studio until January 15, 1962. Half of the property, comprising 2.88 acres was acquired in August 1943, and the remainder in April of 1955.”

The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner reported in May of 1962 that: "15 FLEE AS D.W. GRIFFITH BUILDING TUMBLES.” The old D.W. Griffith Studio, a Hollywood landmark for nearly half a century, was gone today after a three-alarm fire wrote a finish fitting to movieland’s tradition of the spectacular. Three firemen were injured and 15 others fought the blaze that shot flames into the air visible from Civic Center. Most recently owned by Columbia Pictures, the old studio extended for a block between De Longpre Avenue and Sunset Boulevard from Virgil Avenue was being demolished. Scaffolding was put up by wrecking crews a week ago."

The venerable and storied movie studio died with a whimper and flamed out in one last blaze of glory.

It changed hands 17 times since it was built. Today it is a supermarket and a parking lot. They paved paradise.

Thanks to Marc Wanamaker of Bison Archives for his additional research. His help is always appreciated.

BisonArchives.com