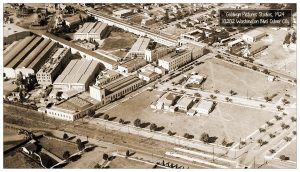

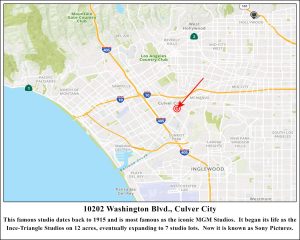

10202 Washington Blvd., in Culver City, "Screenland USA"

The Famous and Iconic

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios

Built by early Mogul, Thomas Ince. Bought by independent icon, Samuel Goldwyn.

Merged with the mighty Metro Pictures. Today is Sony Pictures Studios and home to Columbia Pictures.

Related Pages:

click to enlarge

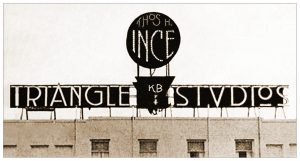

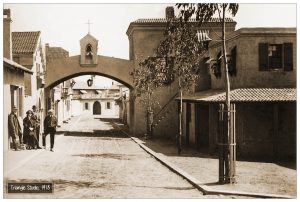

Triangle Motion Picture Company

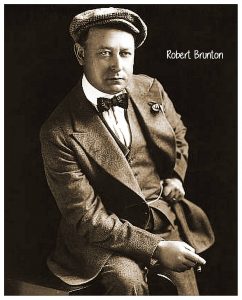

Ince-Triangle Studio

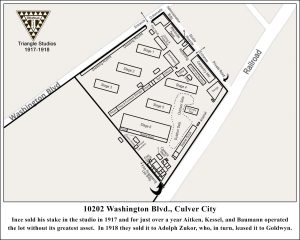

10202 Washington Blvd., Culver City

1915-1918

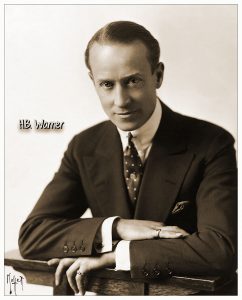

By the time he built this studio in 1915, Thomas Harper Ince was one of the top producer/directors in the business. His peers were the biggest directors of the day: D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, and Mack Sennett. People waited for a Thomas Ince film and asked theater owners to show them.

This studio was Ince's second. His Inceille in Santa Ynez Canyon (now Pacific Pallisades) was still a working studio and would serve as Ince's backlot for this new studio. He used it for his exteriors while using the new plant for the interiors.

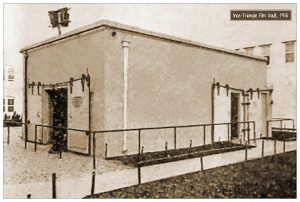

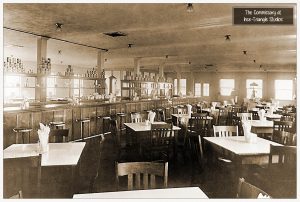

While at Inceville, Ince single-handedly revolutionized the movie-making process and created the role of the Producer. By supervising several production managers, who supervised several directors, Ince provided the model of what would become the "studio system." From his office, Ince could supervise the activities of the entire studio. As a self-contained studio, everything was done on-site, from scriptwriting through producing the final print for distribution. He even provided meals for the employees and housing, when necessary.

Culver City

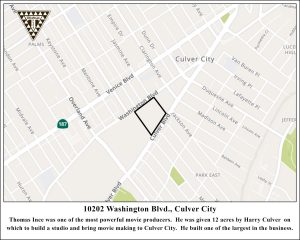

Harry Culver was a real estate developer. He owned several square miles of land that he named after himself calling it Culver City. He thought a good way to make a lot of money would be to give land to movie companies and attract studio employees to build homes. Small businesses should follow to provide for new residents.

Culver gave Ince (yes, gave) 12 acres of land with this condition: build a movie studio on the land. Culver was right. It worked. Ince built the studio, and the studio employed hundreds of people, businesses opened, and Culver City flourished.

Harry Culver became a very wealthy man. And Thomas Ince had his new studio.

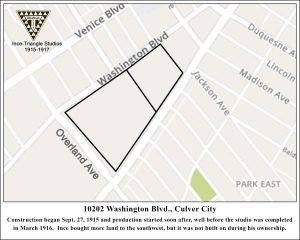

Constructed began September 27, 1915, and production began at the new studio almost immediately, even though construction was not completed until March of 1916 when the official opening took place.

It was bound on the northwest side by Washington Blvd., which was just a dirt road at the time. Culver Blvd. along the southeast edge was not yet a road, but a commuter railroad line. Before the studio construction was completed, Ince bought an additional 21 acres to the southwest for a total of 33 acres, although the additional area was not put into production during the time of Ince's and Triangle's ownership. That edge of the studio was bordered by Overland Ave. which made the studio roughly triangular in shape.

Triangle's formation

Triangle was the brainchild of Harry Aitken, former President of the very powerful Mutual Film Company, the first big competitor to Thomas Edison's General Film Company, the behemoth film distributor. He was also the President of both the Reliance and Majestic motion picture companies.

In 1914 Aitken partnered with famous producer/director D.W. Griffith to produce and distribute what turned out to be Griffith's masterpiece and his highest-grossing, highest profit film, The Birth of a Nation. Aitken's partners in Mutual Film thought it too risky a venture to be involved in and they collectively voted against Aitken. It was a very high budget movie with a lot of promise but no guarantees. So Aitken and Griffith formed a one picture partnership (with several other investors) and financed, produced, and distributed the film themselves. The Birth of a Nation was a huge hit and made Aitken and Griffith, and their other partners a great deal of money.

A new partnership

Hollywood's story is filled with complicated relationships. Partners came and went. Friends became adversaries then become friends again. It could be quite incestuous. The story of Triangle Motion Picture Company (initially announced in the trade papers as Triangle Distributing) was one such story.

After the success of the Griffith film, Aitken wanted a larger slice of the industry's pie. His plan was to form relationships with other industry heavy-hitters. He negotiated with another one of the large conglomerates, New York Motion Picture Company, and its owners Charles and Adan Kessel, and Charles O. Baumann. who brought in their subsidiary, Kay-Bee Pictures, and their most powerful employees, Mack Sennett and Thomas Ince.

The new company was formed to distribute the pictures of Griffith, Sennett, and Ince, who were all made partners in the new venture. Each brought a studio with them. Griffith's Fine Arts Studio in East Hollywood, Sennett's Keystone Studio in Edendale, and Ince's new Culver City studio (along with his Inceville).

Three major movie makers, Three studios. They formed a triangle of heavy hitters. Hence the name of the company, Triangle Motion Picture Company.

The Ince-Triangle Studio was the most modern ever built. It was here that Ince made his famous masterpiece, Civilization and many other movies popular with the film-going public.

click to enlarge

Ince on the move

By 1917 Thomas Ince was tired of the restrictive relationship he had with Aitken, Kessel, and Baumann. As businessmen, they wanted to hamstring his creative control with business considerations. Ince wanted out. By June of 1917, Ince had negotiated a buyout with his partners.

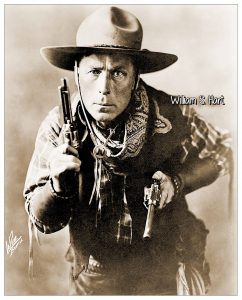

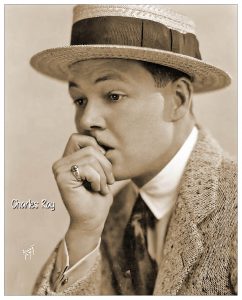

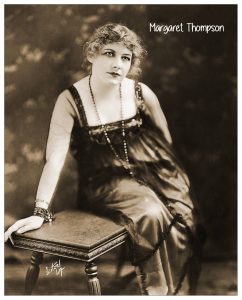

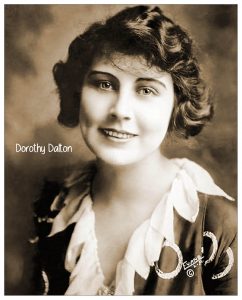

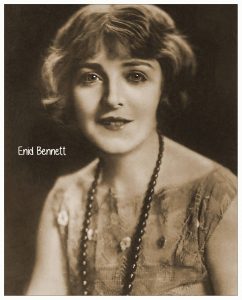

He brought with him many of his stars, including his friend William S. Hart, as well as others including Charles Ray, Dorothy Dalton, and Enid Bennett, and more. He rented Griffith's old studio on Girard St. in Los Angeles while his new studio (land bought from Harry Culver) was being built just a mile north. He signed a deal with Adolph Zukor's Artcraft to distribute his movies.

By December of 1918, his new studio was ready for production.

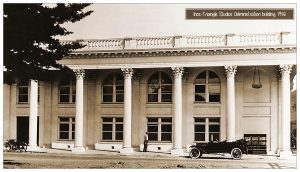

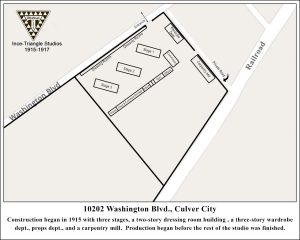

So he could begin production right away, Ince built one stage plus a long, narrow two-story dressing room building extending 500 feet along Washington Blvd. for his stars and other players. Two more stages were quickly erected behind the dressing rooms and behind the stages, he built a long, narrow prop room and storage area that bisected the lot into two 6-acre segments. Along the northeast side, he erected a three-story wardrobe building. The administration building came after 3 more stages and film lab were added on the far side of the lot.

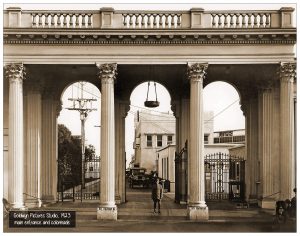

He put his "studio system" into immediate practice. Next came the commissary and several other support buildings, including the scene dock, prop department, carpentry mill. By the time of the official opening of the studio in March 1916, three more stages were built, as well as the famous administration building, with its iconic colonnade facade facing Washington Blvd. The Washington Blvd. side ran 500 feet.

Ince's time at this studio was rather short. Less than two years but accomplishments were great. He made his masterpiece, Civilization, he built Hollywood's largest studio and established a system that we now know as the studio system, allowing dozens of productions to run simultaneously, with a tiered system of producers, production managers, and directors.

Ince's Hidden Ace

In 1917 Ince, Griffith, and Sennett fell out with their partners. They became dissatisfied with dwindling creative control over their pictures.

All parties were interested in ending the relationships.

After intense negotiations in New York in which he held out for maximum value, Thomas Ince sold his interests in the Triangle studio and company to his partners, Harry Aitken, Charles O. Baumann, and Adam Kessel. Griffith had left the company a few months before Ince, and Sennett would leave a few months after. Both negotiated and held out for what they felt they deserved, as well. Griffith sold his studio back to Triangle, Sennett bought his from the company outright. Ince, the largest shareholder in Triangle, was ready to get out completely. He was done.

Once the transaction was completed, the remaining partners told Ince to pack his bags and get the hell out of their studio. Thomas H. Ince just grinned. He had a hidden Ace up his sleeve.

“All right," he said to them. "Now, you get your studio off my land.”

The perplexed partners wondered what he was talking about. Ince showed them his deed. As it turned out Ince was the sole owner of the land that the Triangle studio stood on. 33 acres worth. If they didn't want to lose their studio, Triangle would have to pay dearly.

Ince negotiated a huge sum of money for the real estate. Then he made a call to Harry Culver. He turned right around, bought 12 acres from Harry, and built a brand new studio half a mile north, where he could still see the Triangle lot.

Ince went on to much bigger things. Triangle was soon out of business.

Triangle Studio

10202 Washington Blvd.

1917-1918

What happened to Triangle after Ince?

Aitken, Baumann, and Kessel tried to keep their chins up, but it was just not possible to stay profitable after their big-name producers left the company. They carried a huge debt load after being forced to buy out Ince, Griffith, and Sennett.

They had to buy Ince's interest in the company, and his share of the studio. Then, adding insult to injury, they were forced to buy the real estate the studio stood on.

They bought Griffith's share of the company and his portion of the East Hollywood Studio.

Sennett, they bought his share of the company, and they reimbursed him for his stake in the "Keystone" name.

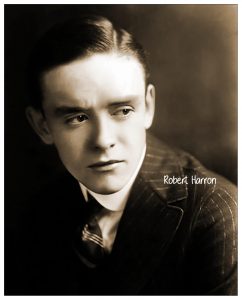

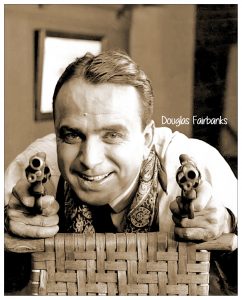

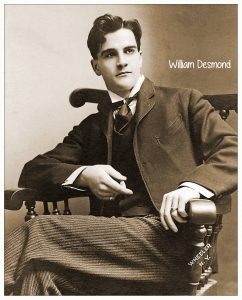

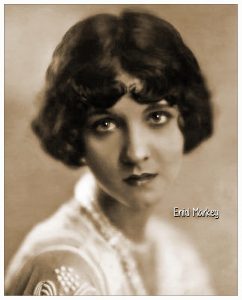

Most of the stars under contract left as well, preferring to stay with the producer/director who hired them. Their two biggest stars, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart, left for more money elsewhere.

The company was gutted. Filleted like a fish. On death's doorstep.

Without big names to draw viewers to their movies, their box office revenue plunged. They took out ads in the trades that looked like acts of desperation, that touted how great Triangle still was.

It was not enough.

To stick the dagger in further, Adolph Zukor, the majority stockholder of Paramount Pictures and Famous Players-Lasky, immediately made independent production deals with Ince, Griffith, and Sennett, paying them large sums to distribute their films for his two distribution companies, Paramount and Artcraft. Then he bought out Aitken, Baumann, and Kessel's former empire for pennies on the dollar, and resold it piecemeal for a good profit.

H.H Hodkinson, Zukor's former partner in Paramount, bought Triangle's Exchanges, again, for pennies on the dollar, renaming it Triangle-Keystone Exchanges. The exchanges still controlled all of the movies produced by the three great producers, and they still had value. The exchanges would changes hands and names for several more years before selling the assets and fading away.

For more than two years Triangle Pictures reigned as one of the largest and brightest companies in the movie firmament. They owned or controlled three of the largest and most modern studios in the business, had three of the biggest names in production making movies for them, and had some of the biggest stars under contract.

For a brief, shining moment, they were one of the biggest names in the film business.

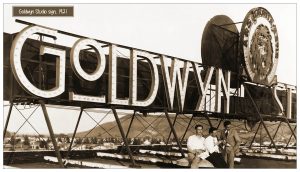

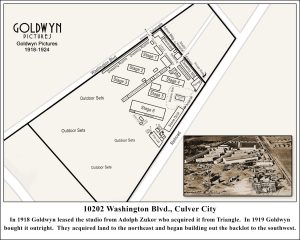

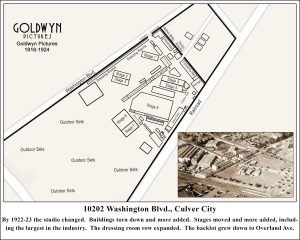

10202 Washington Blvd.

1918-1924

"In this business, it is dog eat dog, and no one is going to eat me."

Goldwyn is a name that lives in Hollywood legend. Samuel Goldwyn has been associated with many acclaimed and Oscar-nominated films. His understanding of the film-viewing public and film as art was greater than any other independent producer to that point.

Sam Goldwyn began his career under another name. His real name. He began life as Szmuel Gelbfisz changing it to the more westernized Samuel Goldfish when he emigrated to the United States in 1899.

In 1913 the 35-year-old Goldfish was a partner, along with friends Jesse L. Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille, in the upstart yet very successful Jesse Lasky Feature Play Company, but in 1916 found himself without a company after the merger of Lasky Company with Adolph Zukor's Famous Players in Famous Plays.

Samuel Goldfish starts a new company

Not ready to give up the movies, he approached successful theatrical impresarios Edgar and Archibald Selwyn. After a good deal of the famous Goldfish arm-twisting, on September 7, 1917, Goldwyn Pictures was born (from parts of each of their last names) with headquarters in New York and they leased they had their first studio, the Solax Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, later also leasing the vacant Universal Pictures studio on Main St., Fort Lee's largest studio.

The move to California

A number of factors lead to Goldfish and the Selwyns leaving the East Coast. East Coast production was becoming too expensive as coal-fired electricity was scarce, expensive, and rationed by the government making Fort Lee production impractical. European sales were down because of the war. And California could provide year-round sunshine for outdoor production.

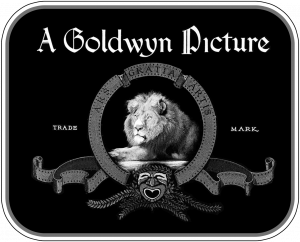

Goldwyn's Lion

This is MGM's iconic mascot, Jackie the Lion. The original lion was an old, toothless, de-nailed lion and began his mascot life as the creation of Samuel Goldfish and the Goldwyn Company. Over the years the lion changed, and the mascot evolved. In one form or another, it has been in continual use by MGM and is still in use today. It has become known as Leo the Lion.

After the major three points of the struggling Triangle Company left the fold (Ince, Griffith, and Sennett), they were forced to give up their Culver City and East Hollywood studios and retrench back in New York. Though little evidence is known to support it, it is thought that the remains of Triangle's California assets were bought by Paramount's Adolph Zukor for pennies on the dollar, including both the East Hollywood and Culver City studios.

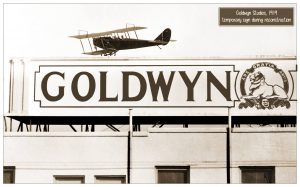

Sam Goldfish and the Goldwyn Company sought new investors and took out a lease on the studio on Nov. 1, 1918. They paid off all their East Coast debts, met the payroll, laid off his local employees, and moved production west, where they could get a fresh start.

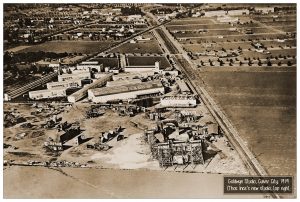

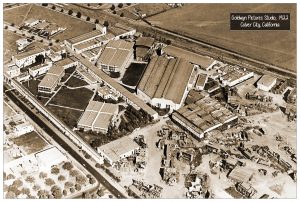

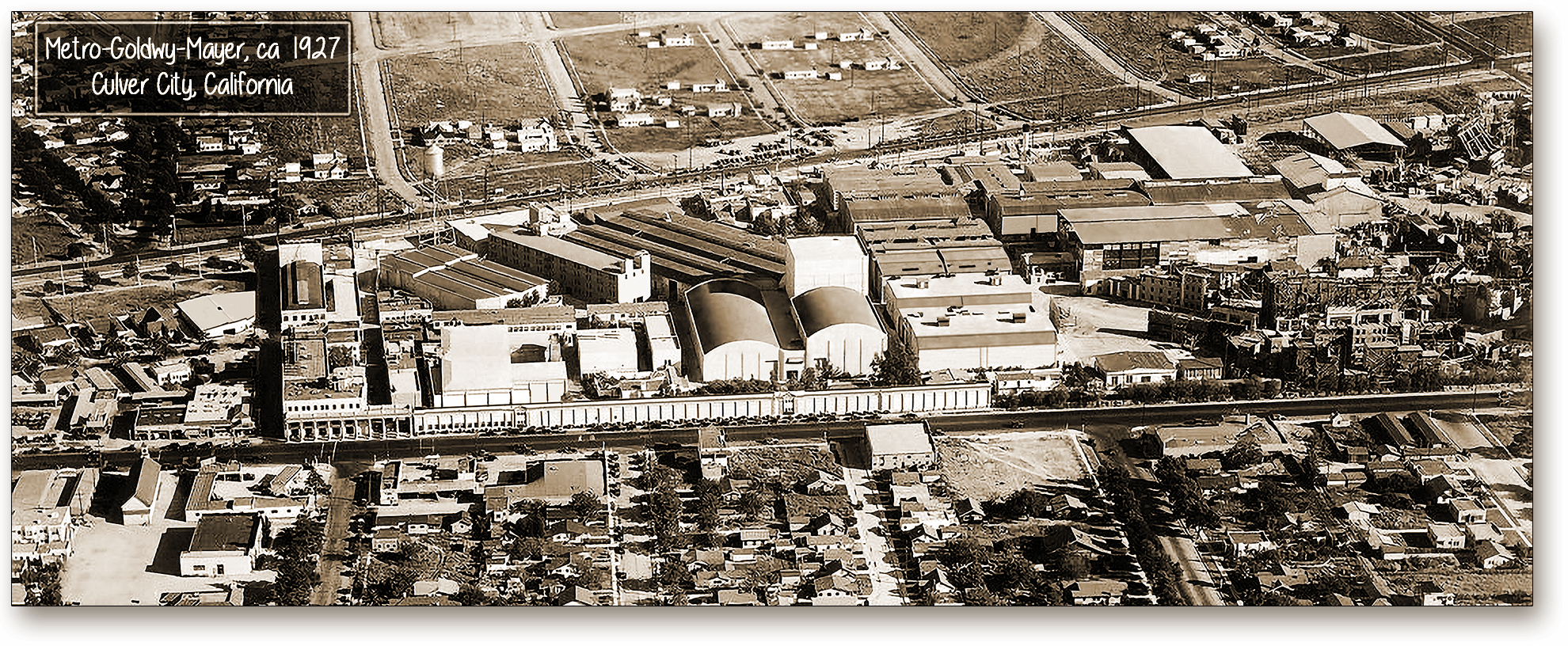

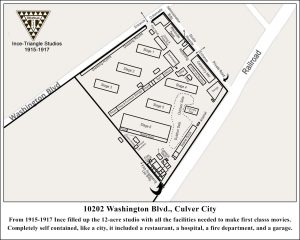

When Goldwyn Pictures came to the Culver City plant, it was one of the largest in the world. Sitting on 12 acres, It had 6 glass-enclosed, lit stages. a 500-foot two-story dressing room complex, a large administration building, a scene dock and prop department that ran the length of the lot, a large commissary, a hospital, a film lab, and an extra 21 acres of undeveloped land to expand.

Big changes for Mr. Goldfish

1919 was an eventful year for Samuel Goldfish. Never one to shy away from insulting others, he provided the ultimate insult to Edgar and Arch Selwyn. He changed his last name to Goldwyn. The Selwyns felt he "stole" their name and the name of the company for himself. They were right, of course, but the courts granted Goldfish the right to call himself Samuel Goldwyn. The name was legally his and all the notoriety that went with it.

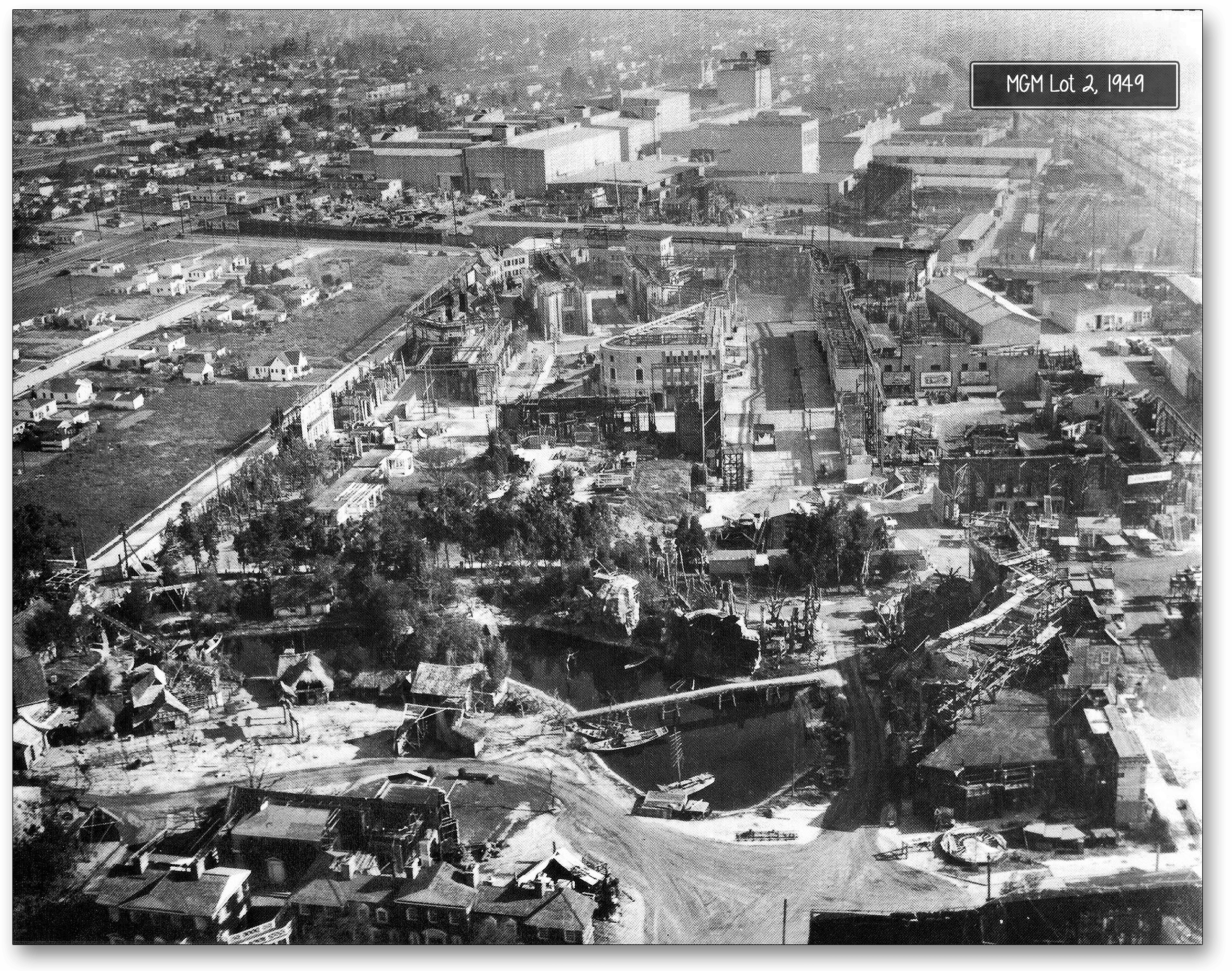

In June of 1919, flush with money from the new investors, Goldwyn Pictures was able to buy the old Triangle studio for pennies on the dollar. With the addition of a few more acres, they now had a 40-acre studio and began to expand onto the vacant land with backlot standing sets. The front lot was reconfigured to put in additional stages and support buildings. Between 1919 and 1924 Goldwyn Pictures had a total of 8 or 9 stages (depending on how you count them) and a backlot that ran to Overland Ave, doubling the size of the production area.

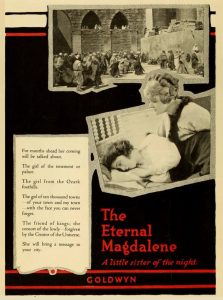

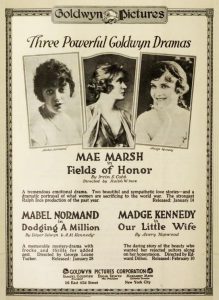

Sam Goldwyn put under contract many leading players of the day. In addition, he put under contract supporting players, the first in the industry to do so, creating a repertory of actors, directors, and writers that could turn out quality motion pictures the public loved. Goldwyn's policy became "fewer but better."

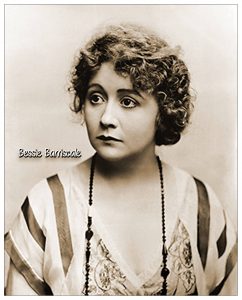

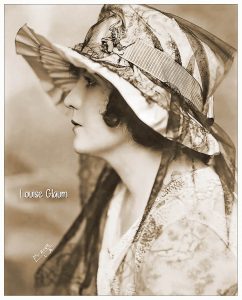

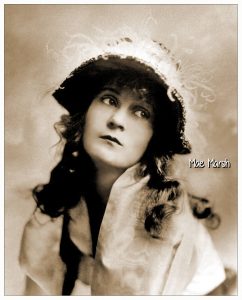

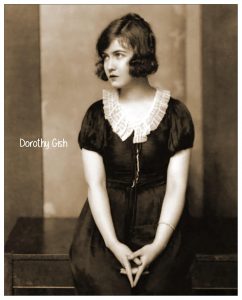

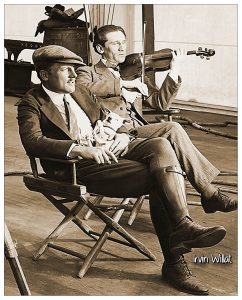

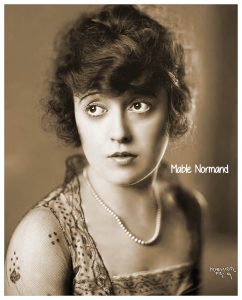

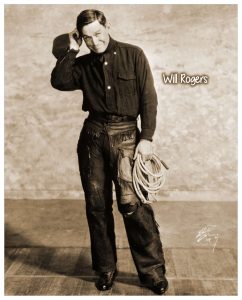

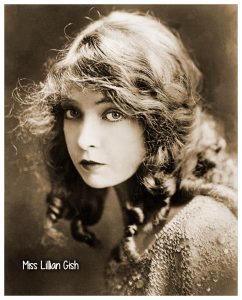

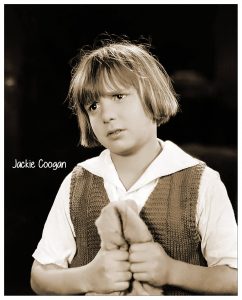

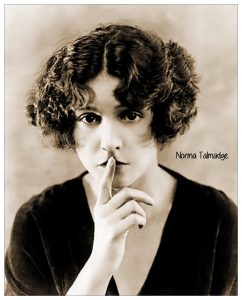

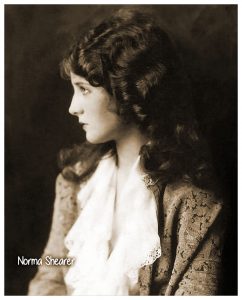

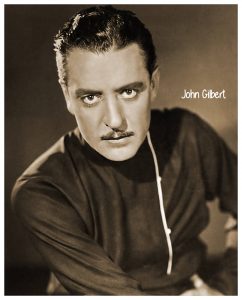

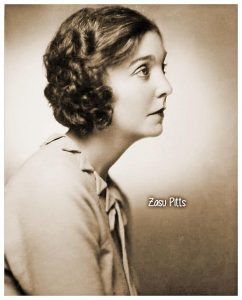

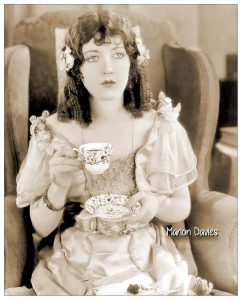

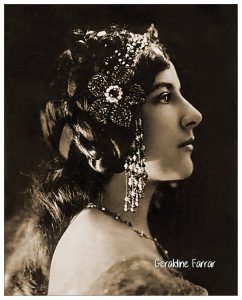

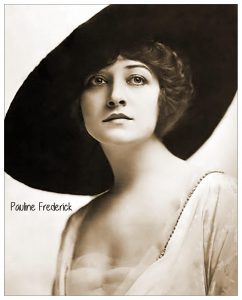

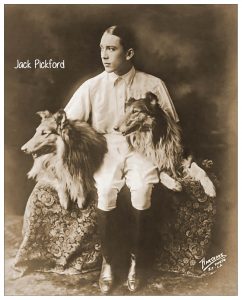

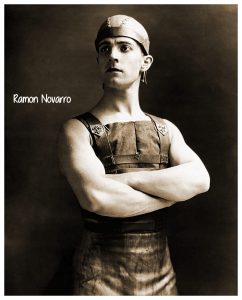

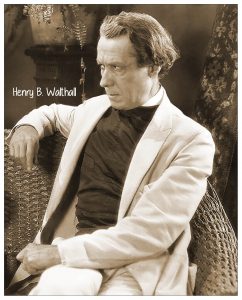

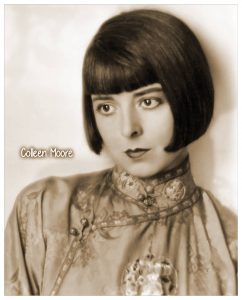

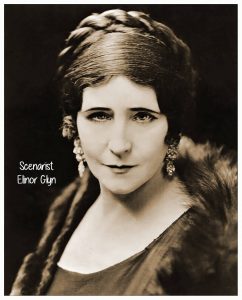

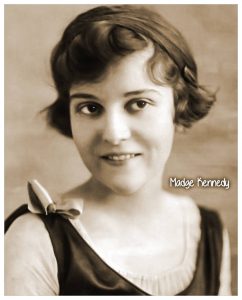

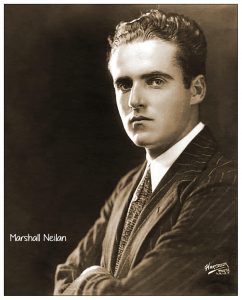

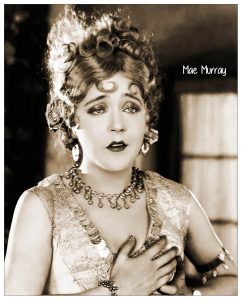

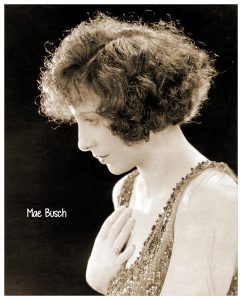

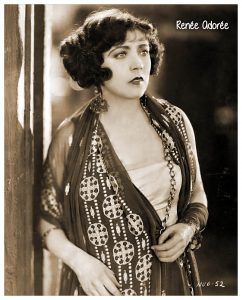

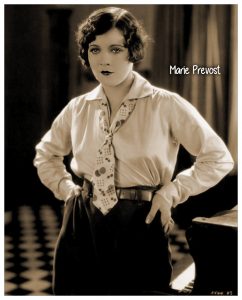

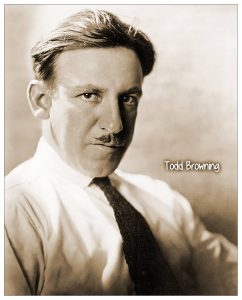

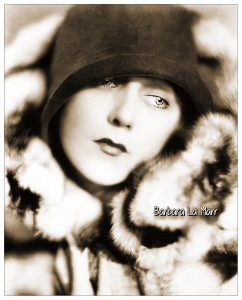

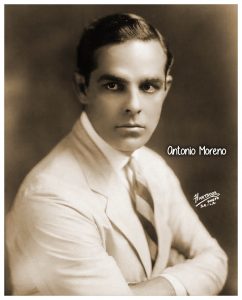

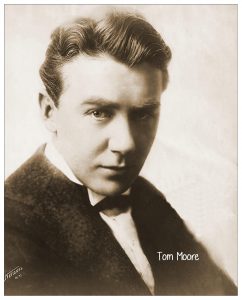

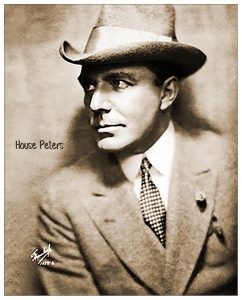

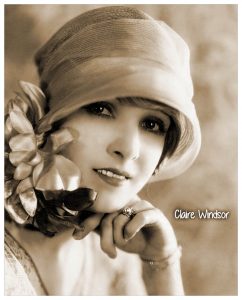

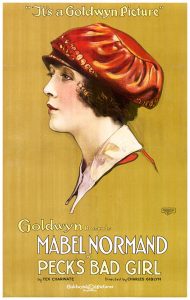

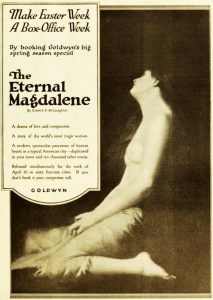

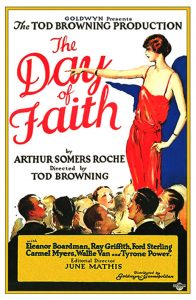

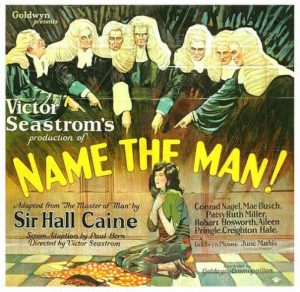

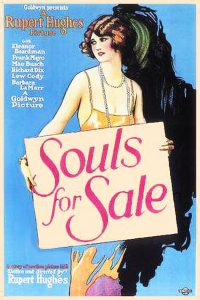

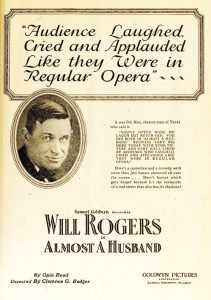

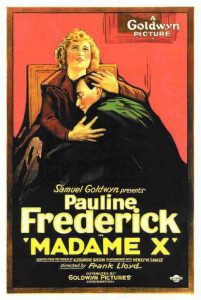

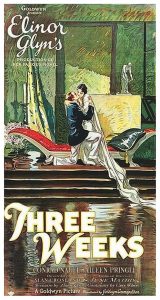

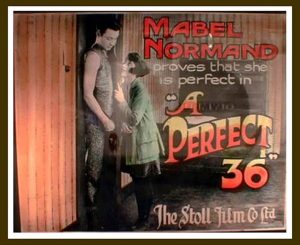

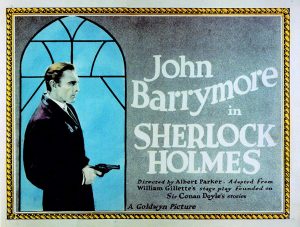

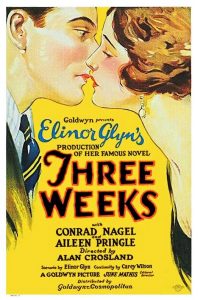

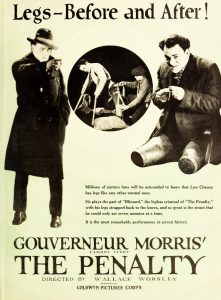

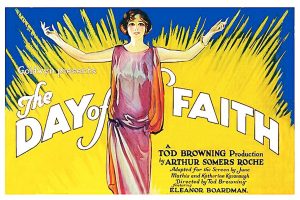

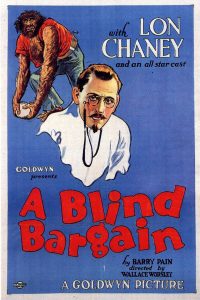

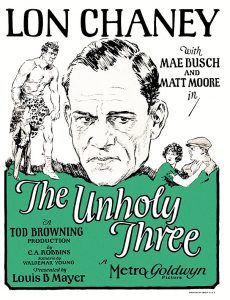

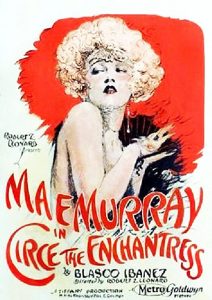

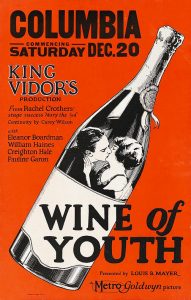

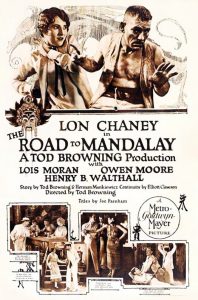

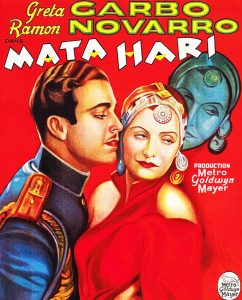

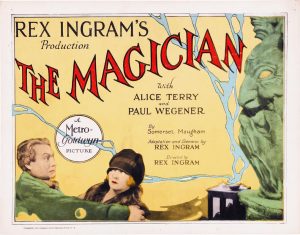

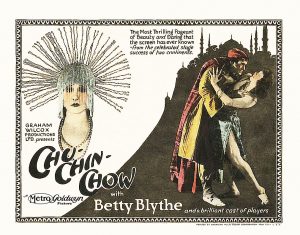

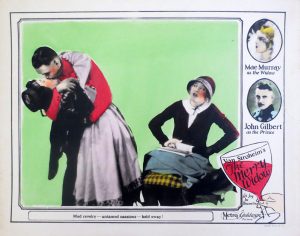

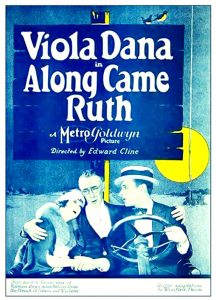

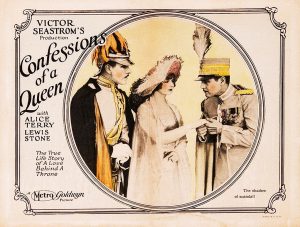

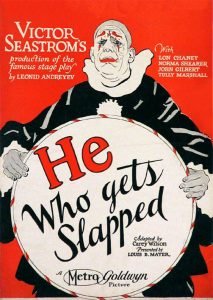

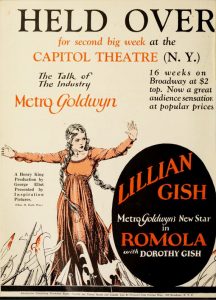

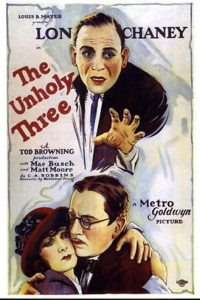

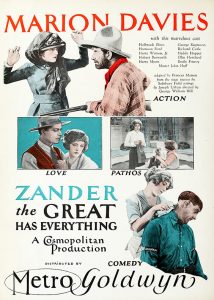

Among its leading players were the most famous comedienne in the world, Mabel Normand, Cowboy philosopher Will Rogers, and "Man of a Thousand Faces" Lon Chaney. Other popular players included Norma Talmadge, Tom Moore, Jack Pickford, Lillian Gish, Geraldine Farrar, Dorothy Dalton, Richard Dix, Mae Busch, Phyllis Haver, Mae Murray, John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, Antonio Moreno, Zasu Pitts, Marion Davies, Norma Shearer, Ronald Coleman, Bessie Love and many more. Directors included King Vidor, Todd Browning, Marshall Neilan, and many others, as well as famous scenarist June Mathis.

By 1923 they now could boast the largest enclosed stage in the business, measuring 300 feet long and 175 feet wide (nearly an acre and a quarter), known as stage 6, and could accommodate 50 movie sets simultaneously. The front lot was full and they began building stages and other buildings on the backlot.

Sam gets the boot

In a most humiliating move, Sam Goldwyn was ousted from the company he founded. It was the second time this happened, the first was his unceremonious removal from Famous Players-Lasky Company, his first co-founded movie company. He would not put himself in that position again.

It happened this way: Sam Goldwyn would push and push and push people until they caved and he got his way. A good trait for a glove salesman, but not good for interpersonal relationships. Most people found him irritating, including one of the company Vice Presidents, Frank Joseph Godsol, who went by Joe. Godsol had talked his way into the company, in a very Goldwyn-ish way, by promising the Goldwyn would absorb Godsol's chain of theaters and would have access to his $5 million line of credit with the DuPont family.

Goldwyn and Godsol fought on nearly every topic, to the point where Godsol vowed to dump Goldwyn and take over the company. In 1923 he succeeded, persuading the majority of the stockholders to vote him out of the Presidency and remove him from the board and the company.

Sam was out. But Sam was not done. He would start a new company, The Samuel Goldwyn Company, and was forever the sole owner, doing exactly as he pleased. He reigned as Hollywood's top independent producer for half a century, long after Godsol, the Selwyns, and his other former partners were long forgotten.

Trouble in Paradise

Without Sam Goldwyn, Goldwyn Pictures was never the same company and began to struggle financially. It stayed afloat due to its association with William Randolph Hearst's Cosmopolitan Pictures, which continued to lease space at the studio and distribute through Goldwyn. But by 1925 the writing was in the wall. Godsol had to do something before the kingdom collapsed.

Frank Joseph Godsol, and the rest of the Goldwyn Pictures board, did not have Sam's sense of art combined with his business acumen. Instead, they thought the way to save the company was to throw unlimited money into extravagant productions.

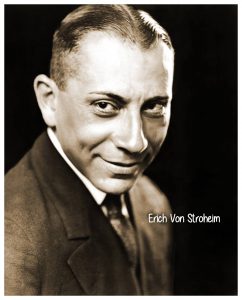

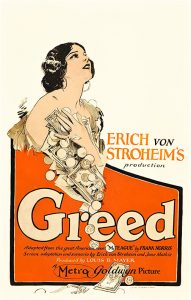

Erich Von Stroheim was asked to direct Ben-Hur but instead chose to shoot the Frank Norris novel, McTeague, but instead of using the studio and backlot, he wanted to shoot a page-by-page faithful production in the exact locations where the novel took place. The result was Von Stroheim's self-described masterpiece, Greed, 85 hours of unedited footage resulting in an eight-plus hour unwatchable film, horribly over budget., Greed was finally cut down to two and a half hours to make it acceptable to audiences but was still a financial disaster...and still a great film.

Rex Ingram was then asked to direct Ben-Hur, but instead, he shot another ridiculously over-budget film with his wife, Alice Terry, in the lead. Vicente Blasco Ibáñez's novel Mare Nostrum. Again, it had to be cut to be acceptable, and still did not make back its costs, even though Terry thought it her best and favorite film.

All three of these films began as Goldwyn, continued through the Metro-Goldwyn period, and were finished and released during the MGM era.

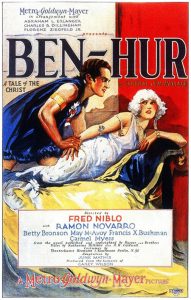

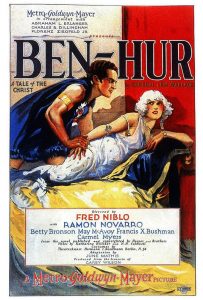

The last production that started under the Goldwyn banner was the classic Ben-Hur. It did not finish as a Goldwyn film...

Metro-Goldwyn Company

10202 Washington Blvd., Culver City

1924-1925

Before Mayer there was Metro-Goldwyn

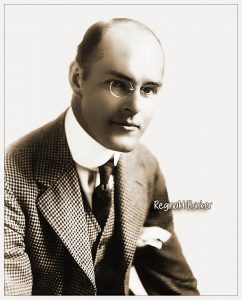

When you hear the name Metro Goldwyn Mayer, everyone knows what we are talking about. But not everyone realizes, if you research the history, is that it was a merger between Metro Pictures Corp. and Goldwyn Pictures Corp. Mayer was never merged in and Louis B. was never an owner or partner, but only an employee...a very well paid employee.

Here is how that happened. Metro was owned by Marcus Loew, the theater magnate. Metro was extremely successful with a large studio in the middle of Hollywood. But they were running out of room so it could not supply enough films to keep Loew's theater chain supplied. He needed more movies. Goldwyn was financially strapped after Samuel Goldwyn was ousted, but they owned one of the largest studios in the country. It seemed like a natural fit. Metro needed a studio, Goldwyn needed money

Legend called it a fateful, accidental meeting. Serendipity. Two studio owners running into each other in sunny Florida while vacationing, and deciding to talk merger. The reality was it was a setup. Lee Shubert, a huge theater owner, helped Loew get started in the theater business by renting him several theaters and backing him financially. He was also an investor in Goldwyn and knew Godsol well. Godsol was also an investor in Loew's theater chain. Shubert suggested to Godsol that he needed a break (wink, wink) and should relax in Florida. Loew had a cold and Shubert suggested that he should go to Florida to recoup (wink, wink).

Whether fate or a setup, Godsol and Loew "ran into each other" in December of 1923 and agreed that they were better off together. They decided on a merger and set their lieutenants, including Loew's second in command, Nicholas Schenk, in motion to make it happen. On April 18, 1924, the merger was finalized through a simple exchange of stock. The two companies became Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation. Aside from the merger, the new firm bought Goldwyn's now-famous logo for an extra $5 million, a roaring lion encircled in a banner with the words "Ars Gratia Artis" ( Art for Art's Sake ).

Metro's contribution was financing, star contracts, a theater chain, and a supply of movies. Goldwyn's contribution was the large 8 stage studio in Culver City, a well-known name, a recognizable logo, a small theater chain, plus strong investors to stand behind the operation, including J.J. Shubert and William Randolph Hearst, and a bevy of well-known players, writers, and directors.

Metro began to plan the move to Culver City, and Goldwyn began to consolidate its possessions to make room for its new partner.

Other productions released during the Metro-Goldwyn era included Lon Chaney's successful The Unholy Three, Eric von Stroheim's masterpiece, and the financially disastrous Greed, and the popular novel Tess of the D'Urbervilles directed by Marshall Neilan. They produced more than 50 features during the Metro-Goldwyn era. Several pictures that began at Metro and at Goldwyn were either finished here or distributed by Metro-Goldwyn.

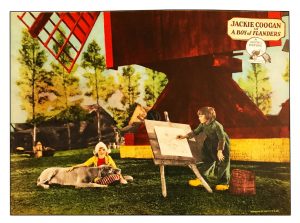

Stars and directors from both companies were brought into the new combine and, in addition to those already mentioned, also included Lillian Gish, Rex Ingram, John Gilbert, Norma Shearer, Marin Davies, Ramon Novarro, Jackie Coogan, Zasu Pitts, Norman Shearer, and many others.

This was a very productive and profitable period for the company and would continue into the MGM era and last into the 1980s.

So...who is going to run Metro-Goldwyn?

Metro-Goldwyn had no studio chiefs, they had been fired. Marcus Loew knew he had to act quickly to keep the ship afloat. He thought he found the right guy in the person of Irving Thalberg, Universal's one-time head of production. There was just one problem. Thalberg was in the employ of, and fiercely loyal to, Louie B. Mayer and Mayer Productions.

Mayer was an up-and-coming producer with his own moderately profitable company and Thalberg was his right hand. Loew quickly realized that Thalberg and Mayer came as a package deal. He hired both, and they all prospered.

Mayer's company was not merged into the new combine. Instead, Loew bought Mayer's assets and hired him to run Metro-Goldwyn. "I would rather make you a partner in the films than a partner in the company" was his attitude. It was a very profitable arrangement for all.

Though never a partner Mayer negotiated a deal that gave "The Mayer Group," (Mayer, Thalberg , and Harry Rapf) 20% of all the profits the company's movies generated in addition to their small salaries. This deal made Mayer the highest-paid executive in the movie industry at over a million dollars a year. Films released by Metro-Goldwyn would be credited as "Produced by" or "Presented by" Louis B. Mayer."

Audaciously, Mayer then proposed that Loew call the company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. His argument was that "three names sound more impressive than two. And, that would give me so much more incentive to work hard out there." Mayer must have been the world's greatest salesman.

By mid-1925 that Loew acquiesced and added Mayer to the banner of the films and finally to the corporate name.

Louis B. Mayer was never an owner, always an employee of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It turned out to be a good move for both Loew and Mayer.

The history of Metro Goldwyn Mayer (and its successors) is well know

and will appear on this site in the near future

MGM sold the studio to Lorimar Telepictures and they sold to Sony Entertainment,

which was the home to Columbia Pictures and its sister, Tri-Star. Their stories will

appear here in the future.

The Ben-Hur Legacy and Near Fiasco

Goldwyn's last and Metro-Goldwyn's first production was Ben-Hur filming in Italy. It would not be finished until the studio became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Considered the most expensive film of the silent era, it was nearly dead in Italy. It had been through a couple of directors, most of the cast had walked out, production costs broke the Goldwyn Company, and the footage was largely unusable.

Now under Metro-Goldwyn and the direct management of Loius B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, the new director, Fred Niblo, was instructed to bring the production back to Culver City, recast it, salvage what footage he could, and finish it as quickly and cheaply as he could. Sets were quickly built, a much scaled-back Circus Maximus set was reproduced on some vacant land a couple of miles from the studio, and the Charriot race completely reshot. They used a composite shot with miniatures instead of extras as spectators. Ramon Novarro and Francis X. Bushman cast as the protagonist and antagonist.

The film was finished as a Mero-Goldwyn-Mayer release. Mayer and Thalberg managed to recoup all of the production costs over the next decade.