In the Heart of Hollywood

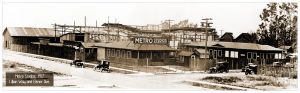

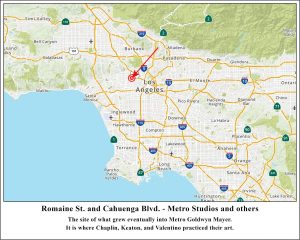

Metro Pictures Studio

The Company That Became the Iconic Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

at 6100 Romaine St, at Cahuenga Blvd.

It is the place of movie legends. Its growth was steady and continuous until it became

the largest movie studio in the world. "More Stars Than There Are In Heaven."

Related Pages:

- Hollywood page

- MGM page

- Richard A. Rowland page

- Marcus Loew page

- Louis B. Mayer page

- Charles Chaplin page

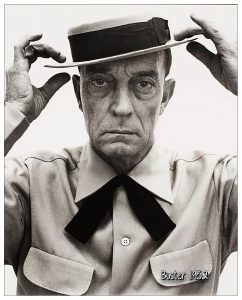

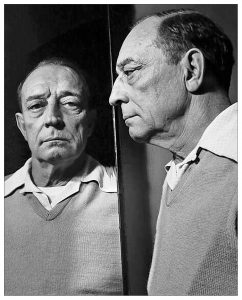

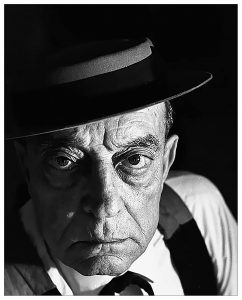

- Buster Keaton page

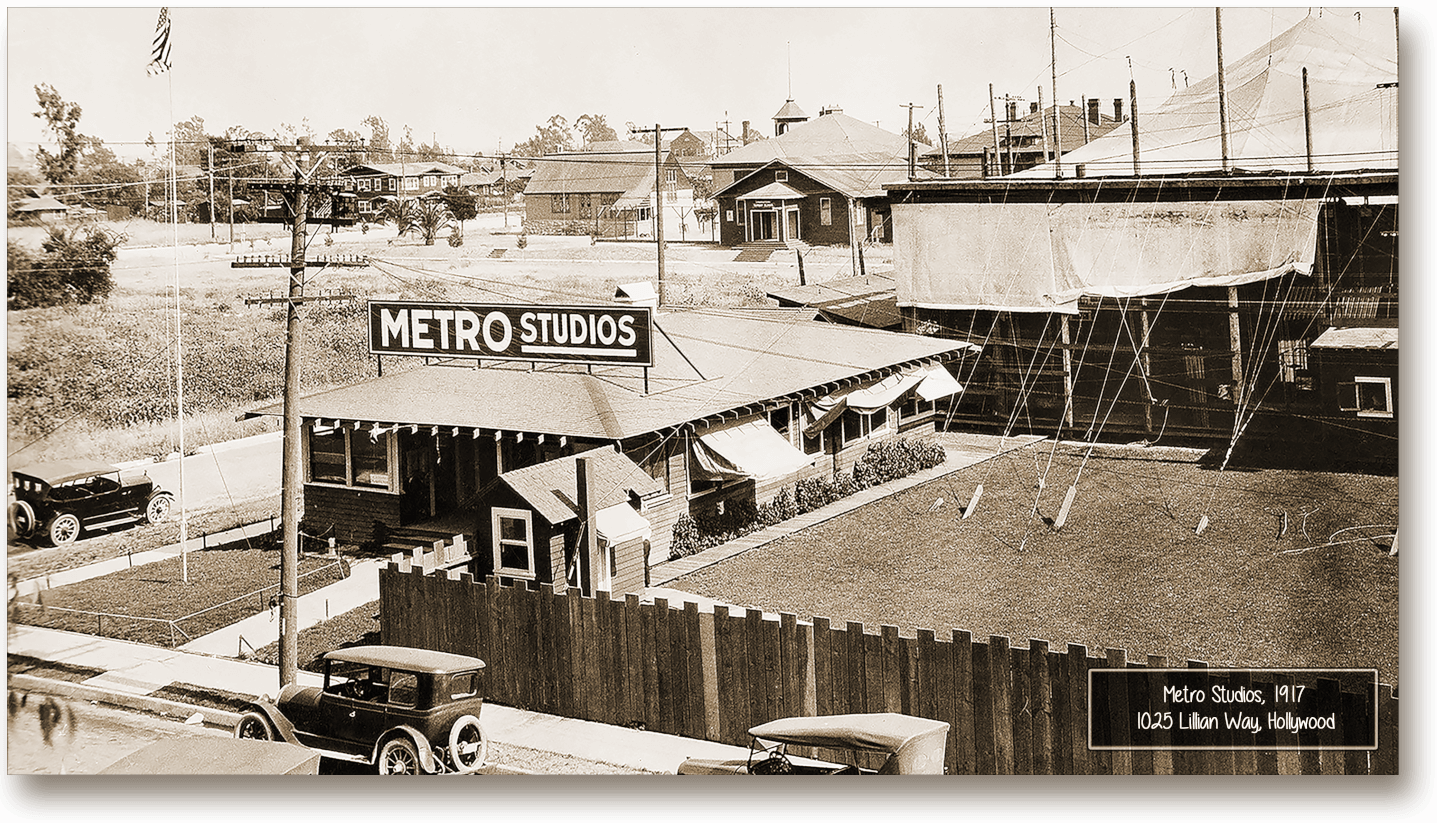

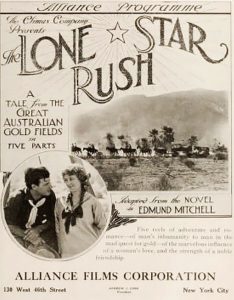

Climax Studio

1025 Lillian Way at Eleanor Ave.

1914-1915

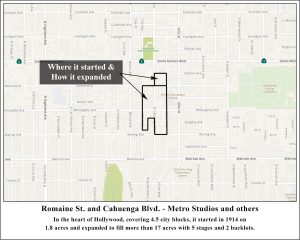

It didn't start out as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It didn't start as six huge movie lots in Culver City. It didn't start here as 17 acres on 4.5 city blocks with two large backlots and 5 stages. It started as a small 1.8-acre studio at the corner of Lillian and Eleanor in the heart Hollywood. It was Climax Pictures Studio, who made only one of their movies here, before they moved on.

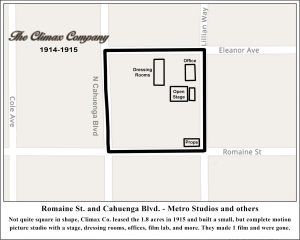

The Climax Company was formed to turn the novels of Edmund Mitchell into movies. It was incorporated on July 28, 1914, by Fred L. Baker with $100,000 in the bank. They leased an empty lot from Cornelius Cole, the former U.S. Senator who owned all the land as far as the eye could see. The lot was bound by Eleanor Ave. on the north, Romaine St. on the south, Cahuenga Blvd. on the West, and Lillian Way on the East.

The Climax Company was formed to turn the novels of Edmund Mitchell into movies. It was incorporated on July 28, 1914, by Fred L. Baker with $100,000 in the bank. They leased an empty lot from Cornelius Cole, the former U.S. Senator who owned all the land as far as the eye could see. The lot was bound by Eleanor Ave. on the north, Romaine St. on the south, Cahuenga Blvd. on the West, and Lillian Way on the East.

The company built a small bungalow for their offices, a 60-foot x 50-foot stage, 20 dressing rooms, a film processing factory, projection room, film vault, scene dock, and artists studio. A complete movie studio in every respect.

Climax produced 10-12 films per year between 1914 and 1920, but only their first, The Lone Star Rush, here. With such small output, the company constantly struggled for financial stability. They abandoned the studio in less than a year and finally, in 1925, they were bought and absorbed by Ainsworth Pictures, Inc.

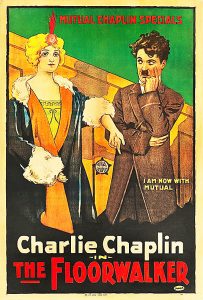

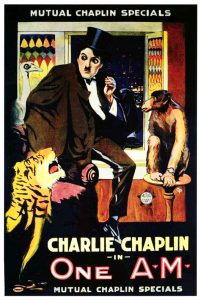

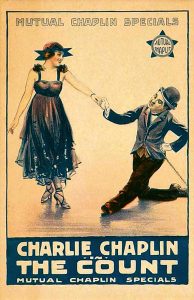

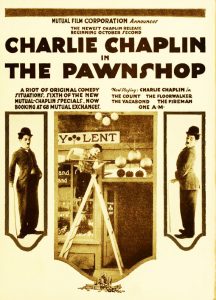

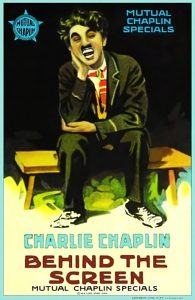

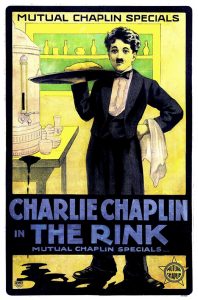

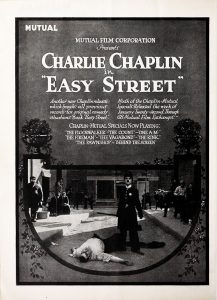

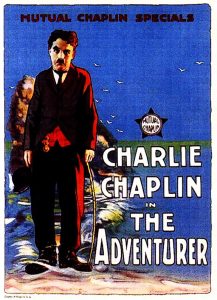

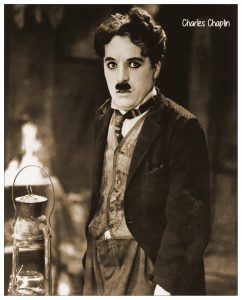

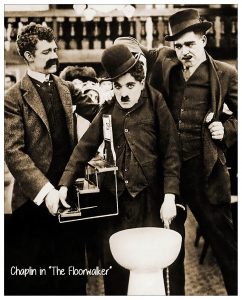

The small studio was acquired by Mutual for use by Charles Chaplin, but before he settled in, it was briefly used by vaudevillians Kolb and Dill for the first of their short string of comedies released by Mutual.

Charles Spencer Chaplin's star was in full ascendance by the time he landed at this little studio at the corner of Lillian Way and Eleanor St. in Hollywood. Right from his start with Mack Sennett's Keystone Comedies in 1914, fans recognized his genius. He thought Sennett's movies were "crude and rough" but he liked the idea of making movies. His were a hit right from the first one, which allowed him to write his own ticket. Frustrated working in Sennett's restrictive environment, he left Keystone within a year and went to work for Essanay where he was given creative freedom. From the start he was directing his own films, developing his unique style, picking his projects and players.

Essanay was one of the big studios out of Chicago. At the time Chicago was a hub of movie-making. He made a dozen movies or so with them at their Chicago, Niles (Fremont, CA), and Hollywood studios.

When his contract was up with Essanay he went shopping. After turning down offers from several big companies, in 1916 Chaplin signed the biggest contract ever. $670,000 for the production of 12 two-reel comedies over the course of 12 months for The Mutual Company. Along with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, this ushered in a new era of very high-priced superstars in the industry, one where the artist had more control over their productions. Mutual President, John Freuler, anticipated the company could pay that amount and still make a nice profit for the shareholders.

When his contract was up with Essanay he went shopping. After turning down offers from several big companies, in 1916 Chaplin signed the biggest contract ever. $670,000 for the production of 12 two-reel comedies over the course of 12 months for The Mutual Company. Along with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, this ushered in a new era of very high-priced superstars in the industry, one where the artist had more control over their productions. Mutual President, John Freuler, anticipated the company could pay that amount and still make a nice profit for the shareholders.

At age 27. Charles Chaplin was the highest-paid person in America.

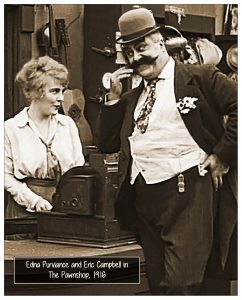

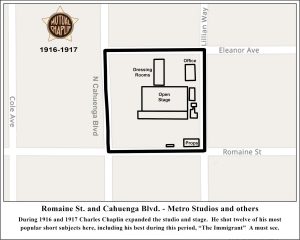

The new venture, The Mutual-Lone Star Co., first leased a small studio in Edendale, just east of Hollywood, before moving Chaplin to this studio on April 15 of 1916. He had built a troop of actors and technicians that he brought with him. Edna Purviance and Eric Campbell were his supporting players along with Charlotte Minueau, Leo White, and Lloyd Bacon. Roland Totheroh and Duke Zalirba were behind the cameras. Mutual hired Henry Caufield away from Universal to manage the studio and the new company.

They expanded the outdoor stage to 150 feet with light diffusers strung across the top to go along with the office building, the film lab, and dressing rooms on the 1.8-acre studio lot. They began turning out his 12 very famous "Chaplin Mutuals," which have since become legendary. His growth as a performer was clear during this period, as was his skill as a director and his creative artistry.

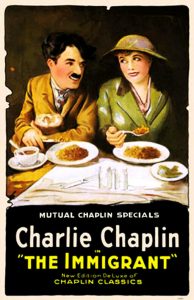

His contract with Mutual called for 12 two-reelers, one every four weeks. The first eight were turned out on schedule, but Chaplin felt this time constraint was too restrictive. To make the quality he desired, he needed more time. So he took the time. These last films were considered his best and. And one, in particular, The Immigrant, was a critical, financial, and popular success.

His contract with Mutual called for 12 two-reelers, one every four weeks. The first eight were turned out on schedule, but Chaplin felt this time constraint was too restrictive. To make the quality he desired, he needed more time. So he took the time. These last films were considered his best and. And one, in particular, The Immigrant, was a critical, financial, and popular success.

This period saw Charles Chaplin emerge as a legitimate artist, recognized by the public and his peers.

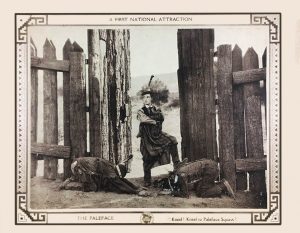

After his 12 picture stint with Mutual, Chaplin took a twenty-week vacation after which he signed a contract with First National for the whopping amount of $1,000,000, the first million-dollar contract in the business.

Mutual sold the Lone Star studio in 1917, but the Lone Star company continued...as the distributor of the Mutual-Chaplin Films paying dividends to all of its stockholders for years to come.

As for Chaplin, we know what became of him. Continued success. He also became one of the founders of United Artists and built himself a studio and backlot on La Brea Ave. in Hollywood, which he owned until the 1950s.

Metro Pictures Corp.

1025 Lillian Way

6100 Romaine Ave.

1917-1924

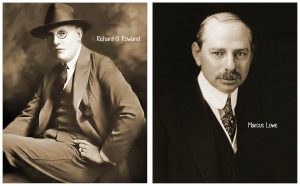

When Richard A. Roland started Metro Pictures Corp. in 1915, he hadn't intended to be a movie producer, as well. But what many companies discovered, including Metro, is sometimes you need to make your own movies to get the quality your customers need in their theaters. Distributors became producers, producers became distributors.

When Roland bought the small studio at Eleanor and Lillian, the industry, and Hollywood, was in full swing. There were already several good-sized studios. But Rowland opened his first studio in New York before moving some production to "The Coast." During its life, Rowland maintained Metro studios on both coasts.

Metro was incorporated on January 27, 1915, in Jacksonville, Florida. Rowland was the corporate president. The corporation's secretary was Louie B. Mayer, who would come into and out of the Metro sphere right up to the merger, when his position became permanent. From its beginning until the merger Metro produced and/or distributed 529 films.

Metro enters the production field

By the end of 1915, Metro produced its first film, Sealed Valley, using studios and locations there in Jacksonville. From that point forward produced its own movies, several in Jacksonville, distributing for itself and other producers and production companies. The company leased studios in fort Lee and New York. And it leased what was, at the time, the world's largest studio in the tiny town of Rocky Glen, Pennsylvania, a 25,000 square foot enclosed stage on 14 acres of land.

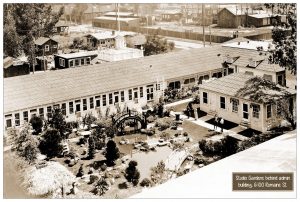

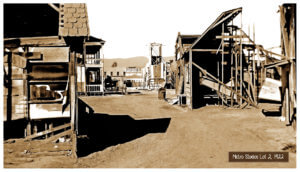

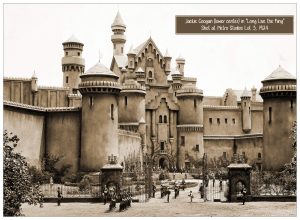

Artist’s rendering of proposed studio at 6100 Romain St. click to enlarge

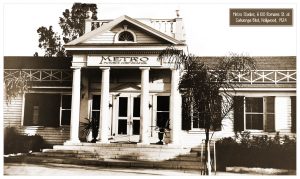

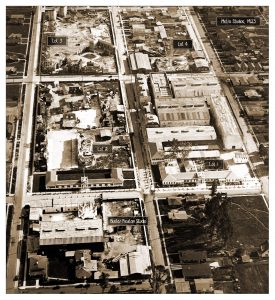

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

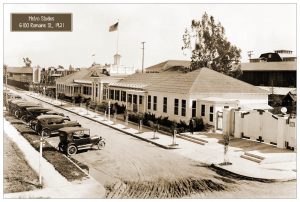

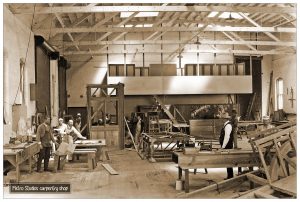

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

Metro expands production to Hollywood

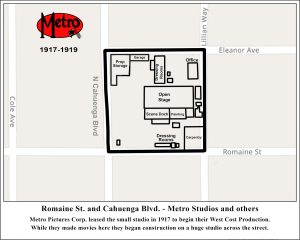

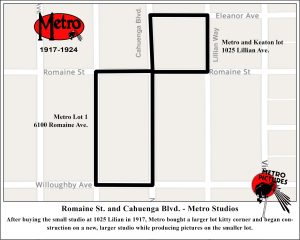

In October 1917 Metro took over this small studio from Charles Chaplin and the Mutual Company and in December began refurbishing the site. Richard Rowland reincorporated and raised significant capital to finance a huge expansion. They bought several small production companies, as well they bought the small Lillian and Eleanor studio. At the same time, they acquired new studio space in New York.

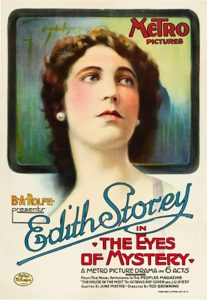

By March 1918 production began at the Lillian Way studio with the B.A. Rolfe production unit, which Metro had absorbed the previous year. By the end of 1918 Metro moved all of its production to the new site and close down all of its other studios. Rolfe was in charge of all production. (By mid-1919 production was so great, they reopened their NYC studio and kept an East Coast production presence until the merger).

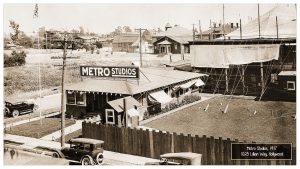

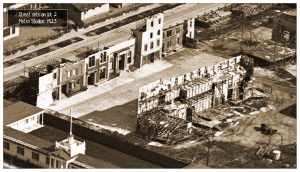

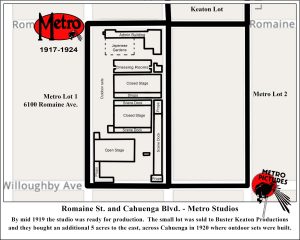

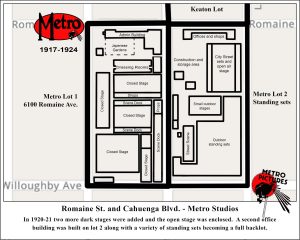

The company builds a large studio

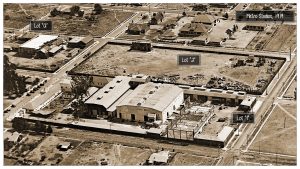

When they bought the 1.8-acre studio at Eleanor and Lillian they also bought 5 acres kitty-corner, at 6100 Romaine St. at the corner of Cahuenga Blvd. and by Nov. 1918 began to build a brand new studio on the large city block. By mid-1919 the new studio was ready and open for business. The administration building was built in the Colonial-style. There were 3 stages: 2 open (70x100) and 1 enclosed lit (70x195). They built 4 projection rooms and 50 dressing rooms including full apartments for the "stars." Behind the office building, the employees could enjoy an elaborate garden with a fountain and bridge." They opened a cafeteria (to keep everyone on the lot at mealtime) and installed an electrical generator to light the stage.

The small Lillian Way property was leased out to Capital Film Co. a small producer, in December of 1919 until future star Buster Keaton moved in during April 2020.

They quickly followed that construction with the purchase of the 7 acres directly across Cahuenga, where they built offices, shops, and outdoor sets. Another block and a half were also acquired. In 1919 a second dark stage was built. In 1920 the company acquired a 65-acre backlot called Rose Hill Park for their growing need for permanent sets. The studio continued to expand and became one of Hollywood's largest.

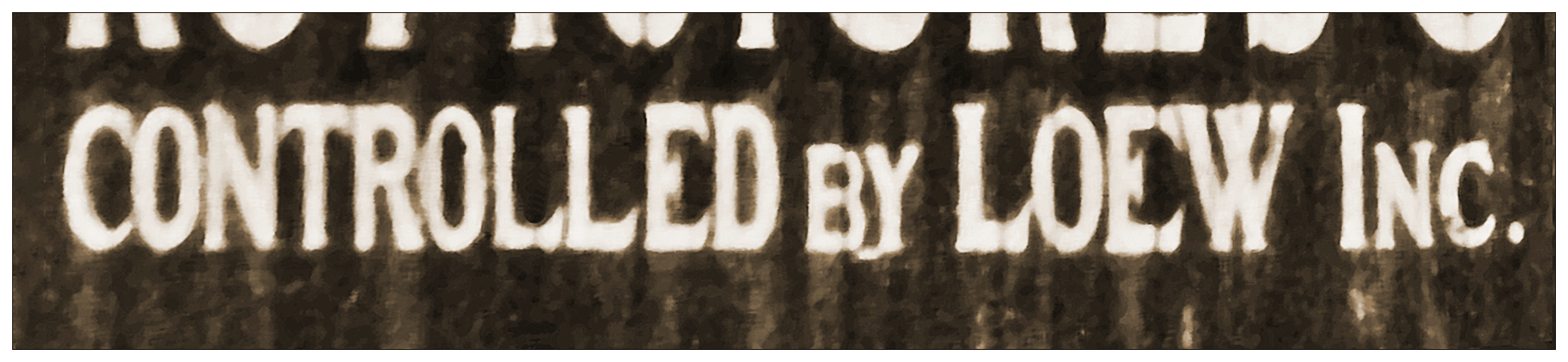

Metro draws the attention of the biggest theater owner, Marcus Loew

Marcus Loew was the biggest name in the movie exhibition business. He owned the country's largest chain, the Loew's theater chain. Realizing, as many movie people did, he needed better control of his product. Sometimes movie producers bought theater chains. In Loew's case, he aimed to buy a studio and control his own production, to feed his audiences exactly what they wanted, instead of being at the mercy of someone else.

Marcus Loew was the biggest name in the movie exhibition business. He owned the country's largest chain, the Loew's theater chain. Realizing, as many movie people did, he needed better control of his product. Sometimes movie producers bought theater chains. In Loew's case, he aimed to buy a studio and control his own production, to feed his audiences exactly what they wanted, instead of being at the mercy of someone else.

In 1920 Loew bought into Richard A. Rowland's Metro Pictures Company, and later acquired Rowland's entire interests and Loew's Inc. became the majority stockholder.

Construction continued at a frenzied pace and by mid-1920 the original lot was packed with buildings, so many that they simply ran out of room.

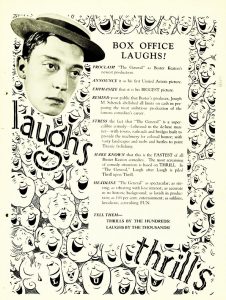

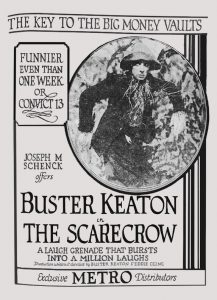

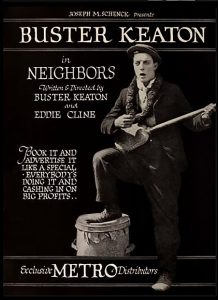

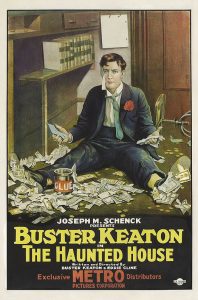

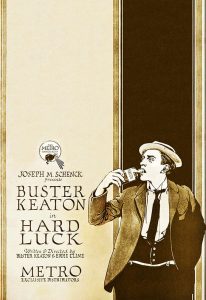

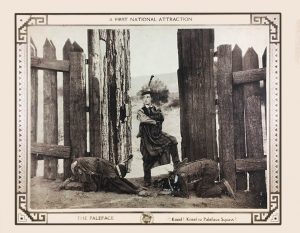

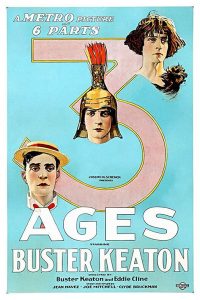

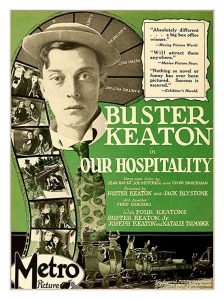

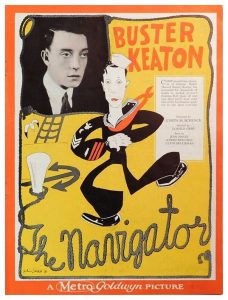

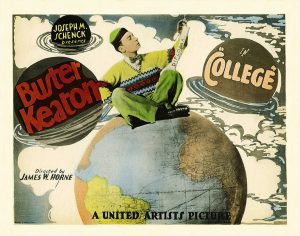

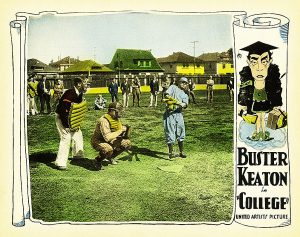

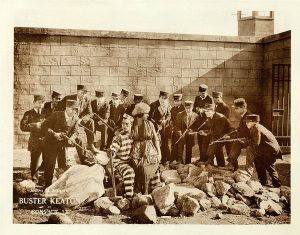

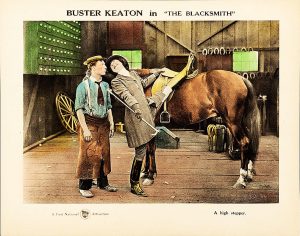

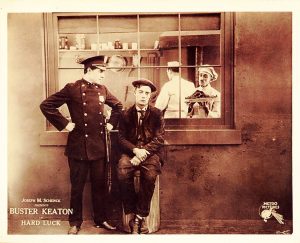

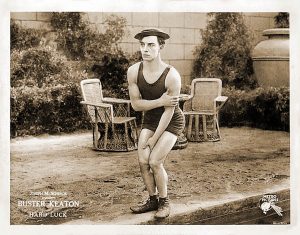

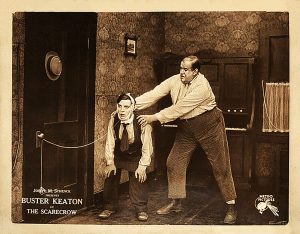

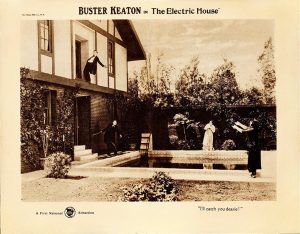

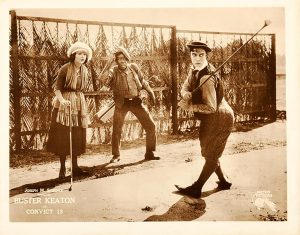

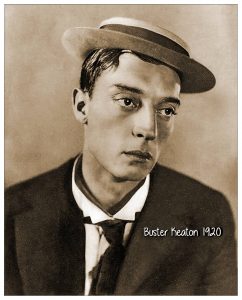

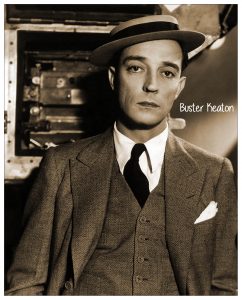

Buster Keaton signs with Metro

Young comedian, Buster Keaton, fresh off a stint in the service during the first world war, signed a new contract with Metro in May of 1920, to distribute his movies. Keaton took over the small Lillian and Eleanor lot as his own base for his movies. Buster would have a phenomenal, if not relatively short meteoric career, and then a devastating crash during his time with Metro.

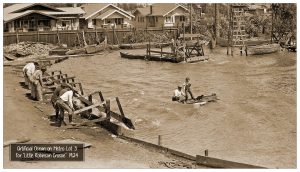

While there, Metro covered the stage for him and built a small backlot for street scenes and more. He would also make use of Metro's backlots, as well.

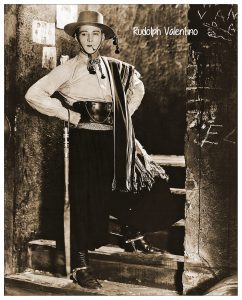

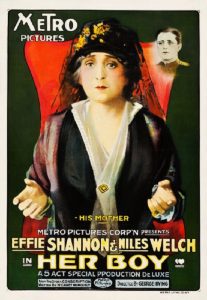

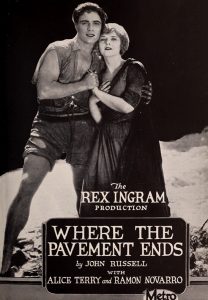

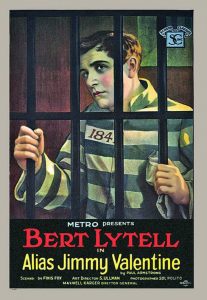

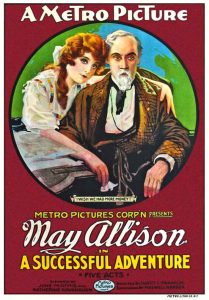

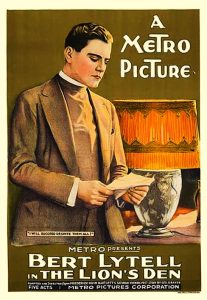

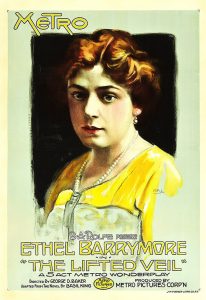

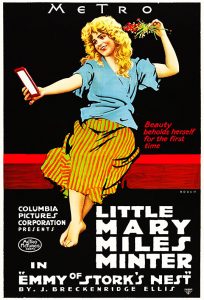

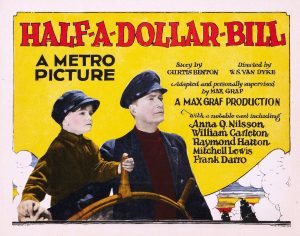

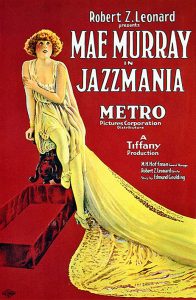

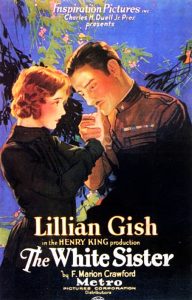

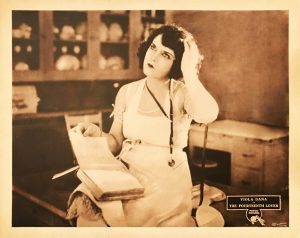

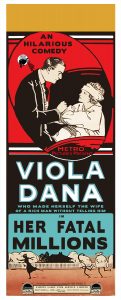

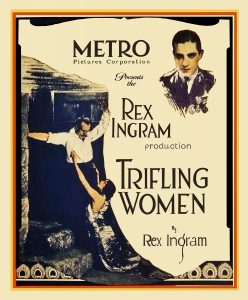

Many of Hollywood's Biggest Stars Graced Metro

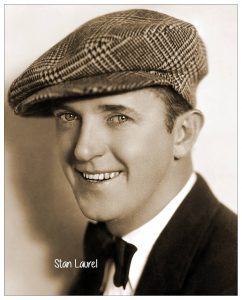

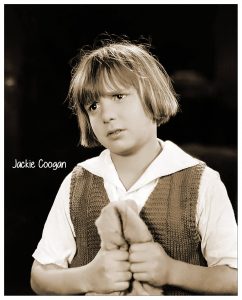

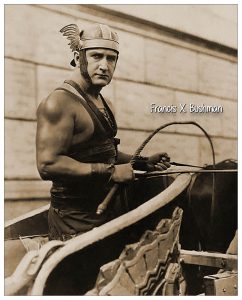

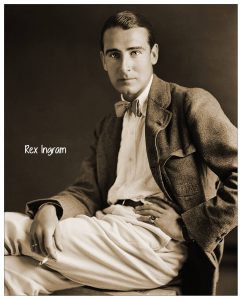

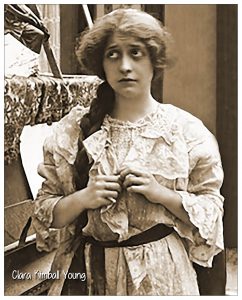

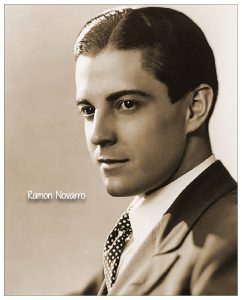

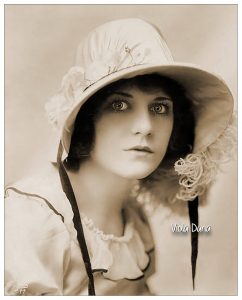

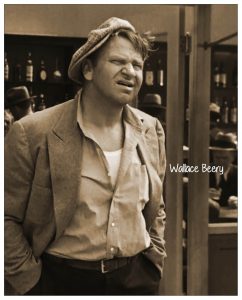

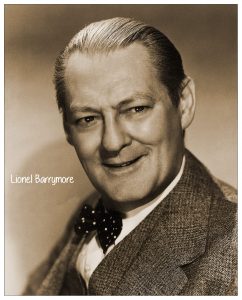

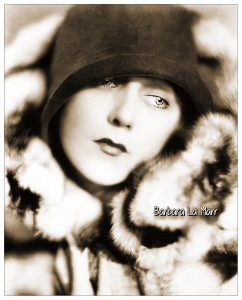

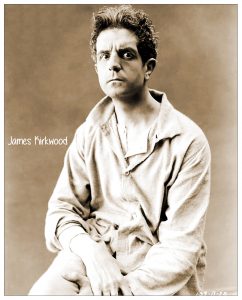

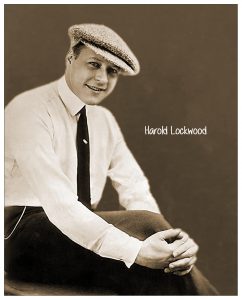

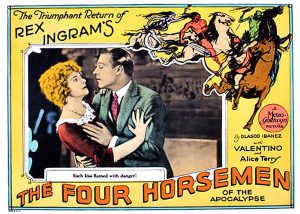

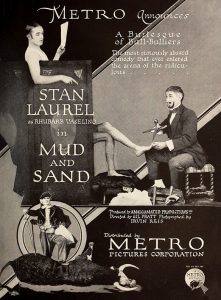

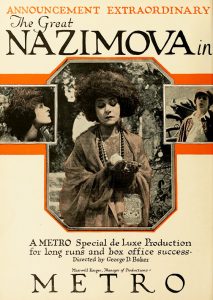

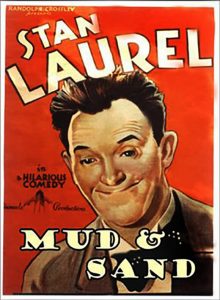

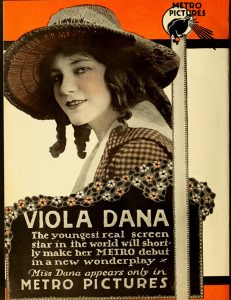

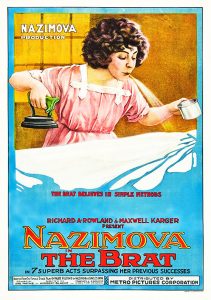

Metro was one of the largest companies to produce movies, and was able to attract many of the big names in the business. Many become Hollywood lore, whose names and faces we instantly recognize. Rudolph Valentino, Buster Keaton, Stan Laurel, Lillian Gish, Jackie Coogan are among the most famous. Other actors were very famous during their time, but are not as recognizable today. They include Francis X. Bushman, Alla Nazimova, Ramon Navarro, Rex Ingram, Wallace Berry, Lionel Barrymore, and many, many others.

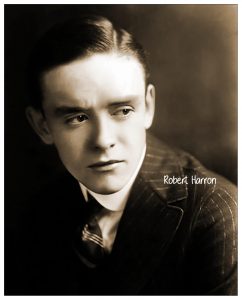

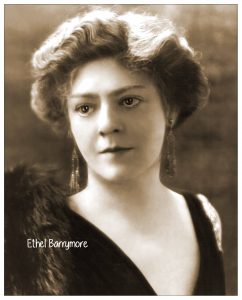

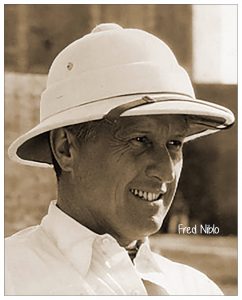

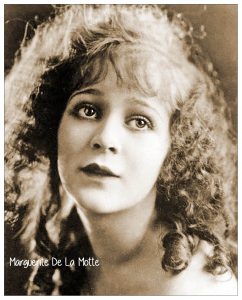

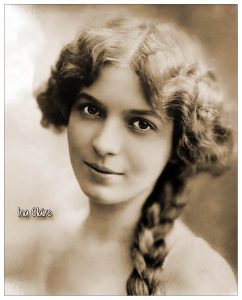

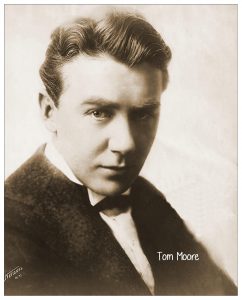

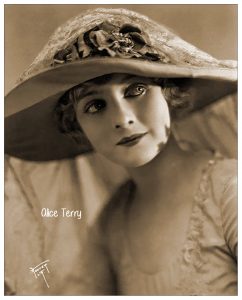

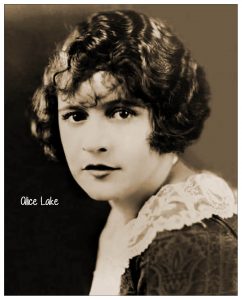

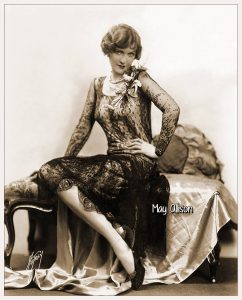

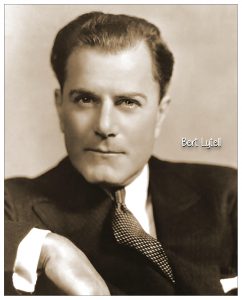

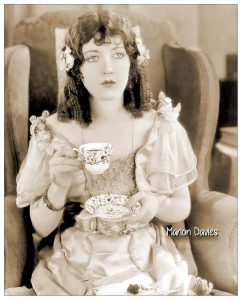

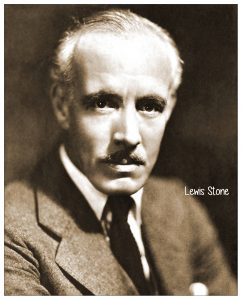

Well Known Stars on the Metro Lot

More Metro Stars and Directors

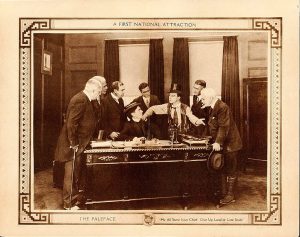

Some of the biggest stars and best movies

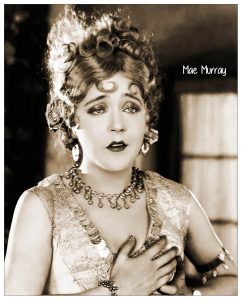

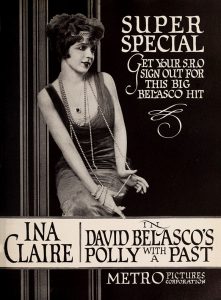

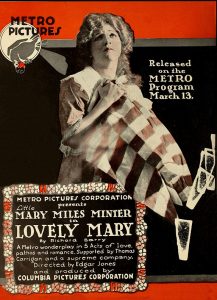

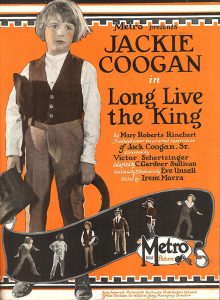

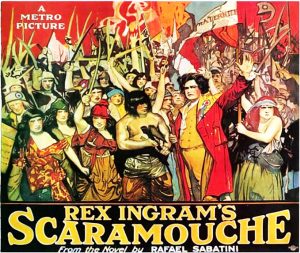

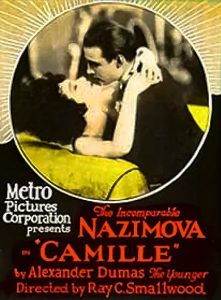

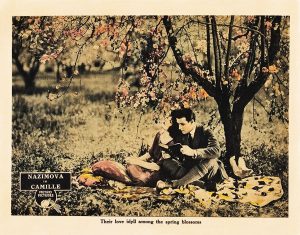

The studio growth was rather complete. Five stages, two backlots, and studio ranch, and as many as twelve simultaneous productions, all vying for space at the large 4.5 block studio. Stars on the roster included Rudolph Valentino and Alla Nazimova (known by their surnames, Valentino and Nazimova). Jackie Coogan, made famous by Charles Chaplin, would sign with Metro in 1923, and directors Rex Ingram and Fred Niblo were regulars on the lot. Stan Laurel made a single film at Metro well before his famed teaming with Oliver Hardy. Lillian Gish was a well-established star. Heartthrob Ramon Novarro and the muscled Francis X. Bushman were also stars who appeared at the studio and would later be teamed in MGM's Ben Hur. The Barrymores, Mary Miles Minter, and Wallace Berry were established stars by the time they came to Metro.

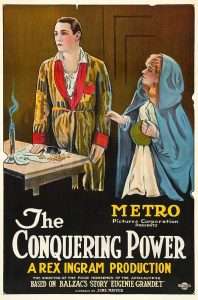

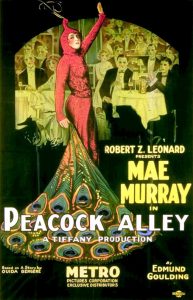

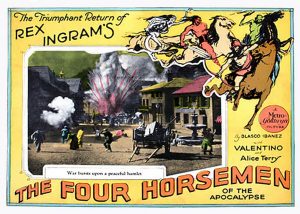

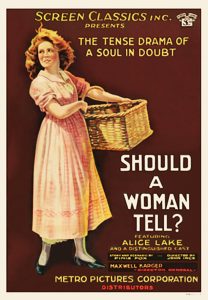

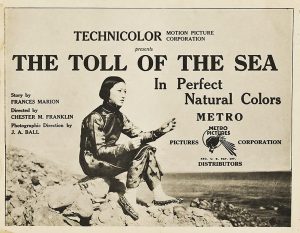

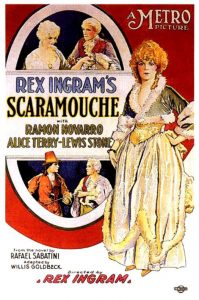

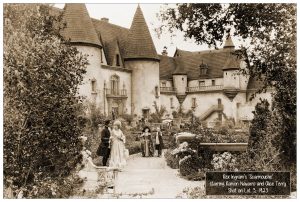

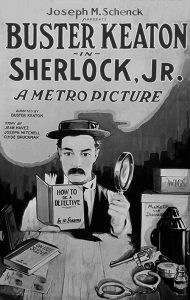

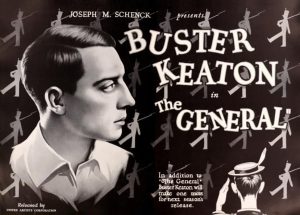

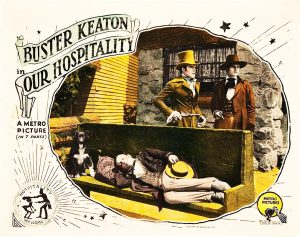

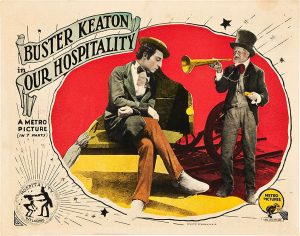

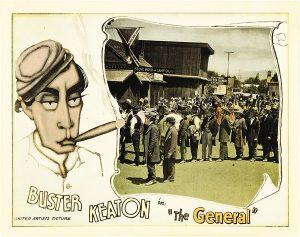

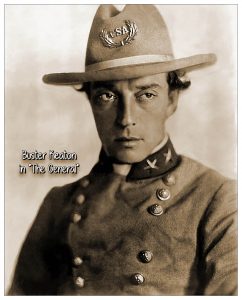

Metro produced and distributed some of the biggest movies of the era. Camille starring Nazimova and Valentino. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse starring Valentino and Alice Terry. Buster Keaton's The General, and Sherlock, Jr. Mae Murray's Peacock Alley. Ina Claire's Polly with a Past produced by David Belasco. Rex Ingram's Scaramouche with Ramon Novarro.

Rowland steps down, Loew becomes President

In January of 1922, Rowland stepped down as President of the company and Loew took over. Louis B. Mayer was hired as head of production.

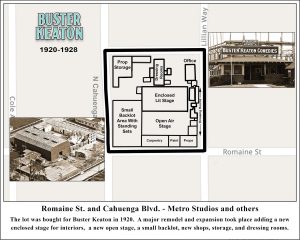

Buster Keaton Studios

Buster Keaton Comedies

1025 Lillian Way

1920-1928

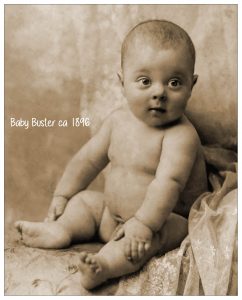

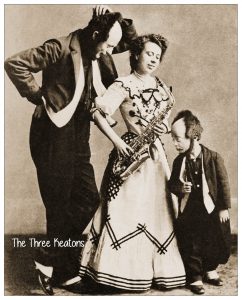

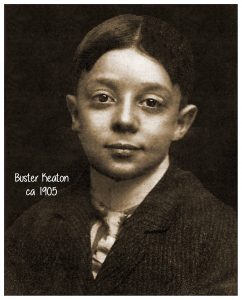

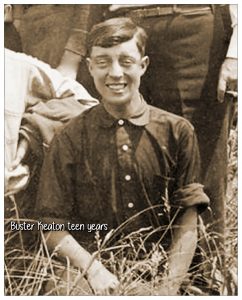

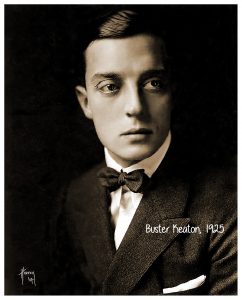

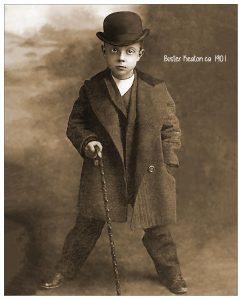

Buster was already a star before he entered "the flickers." He was famous as one of "The Three Keatons" vaudeville act. He was born on the road while his parents, Joe and Myra, toured the country in their successful act. Just before his fourth birthday, he was incorporated into the act, a physical comedy act. Buster became a "social issue." If there had been child labor laws and child abuse laws with any teeth, his father may have been convicted of abuse, and the act may have broken up. We may have never heard the name, Buster Keaton. But he loved being tossed around the stage by this father, and became known as "the human mop." Audiences loved their act, and "The Three Keatons" became very popular around the country, playing all the big vaudeville theaters.

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton was born on October 4, 1895, in Piqua, Kansas, a stopover on the road. He got his nickname Buster, lore tells us, from family friend and fellow vaudevillian Harry Houdini, who watched the youngster fall down a flight of stairs and come up laughing. Houdini commented, "that the fall was quite a buster." The name stuck. He was the first person, as far as can be determined, to be called "Buster."

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton was born on October 4, 1895, in Piqua, Kansas, a stopover on the road. He got his nickname Buster, lore tells us, from family friend and fellow vaudevillian Harry Houdini, who watched the youngster fall down a flight of stairs and come up laughing. Houdini commented, "that the fall was quite a buster." The name stuck. He was the first person, as far as can be determined, to be called "Buster."

Keaton's chance meeting with Roscoe Arbuckle, the famed "Fatty" Arbuckle," immediately led to Buster being cast in Arbuckle's The Butcher Boy and led to a contract to make movies with Arbuckle's company, Comique Comedies. His teaming with Roscoe, and Arbuckle's nephew, Al St. John, led to a series of extremely successful comedies, and a lifelong best-friendship between Buster and Roscoe. The small comedy group, with a company of players, moved around the country landing in Hollywood, taking over a series of studios to make their movies, never having a studio of their own.

All the while, the public and the industry had a growing awareness and love for the unique comedy style of Buster Keaton.

Buster gets a studio

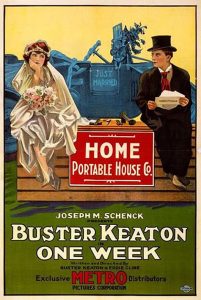

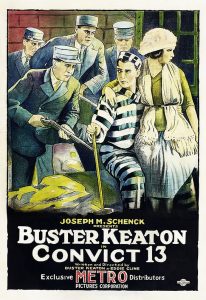

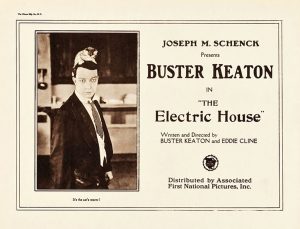

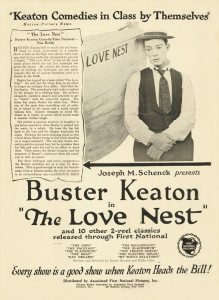

As Roscoe Arbuckle's star began to fade, his partner, Joseph Schenck, recognized Bust er's talent and made Keaton an offer to star in his own comedies. Schenck started a new company, Buster Keaton Comedies, bought the old Chaplin-Mutual studio from Metro. They gave it a dust-off and a coat of paint, put up a new sign on the front, and Buster Keaton moved into the Buster Keaton Studio, the same small studio Where Charles Chaplin made his famous Mutual Comedies.

er's talent and made Keaton an offer to star in his own comedies. Schenck started a new company, Buster Keaton Comedies, bought the old Chaplin-Mutual studio from Metro. They gave it a dust-off and a coat of paint, put up a new sign on the front, and Buster Keaton moved into the Buster Keaton Studio, the same small studio Where Charles Chaplin made his famous Mutual Comedies.

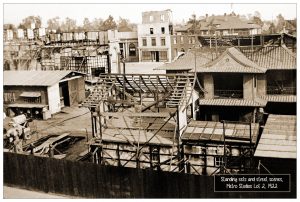

In 1920 the studio was a cluster of small buildings and an open-air stage, very much the same studio that Chaplin used. But Buster wanted to make feature-length films (while Chaplin and Lloyd were content with comedy shorts) and to have complete control over them. So, in 1921 he set about to replace the open-air stage with a large enclosed stage where he could shoot his interiors. He built a large open stage and a small backlot area next to the stages for a few standing for shooting exteriors. He also used the larger Metro backlots across the street and moved onto location for many of his films. He remodeled the existing buildings and dressing rooms and constructed new shops and prop buildings. He wanted more than just a stage, he wanted a full and complete studio. He got it.

Buster becomes a major star

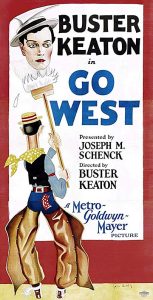

Along with Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, Buster was one of the "Big 3" comedy stars of the 1920s silent era. There were others. Laurel and Hardy came along late in the silent period. Charley Chase and Harry Langdon were popular, not not like Buster. Mabel Normand and Roscoe Arbuckle lost their careers early in the 1920s. And there were others. But Keaton, Chaplin, and Lloyd reigned supreme.

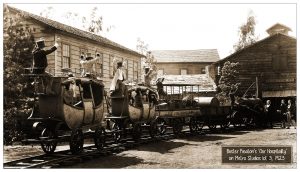

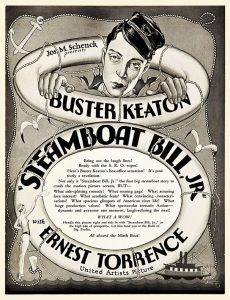

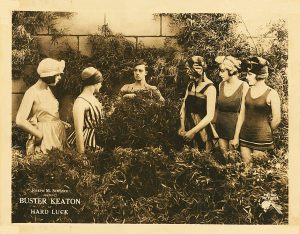

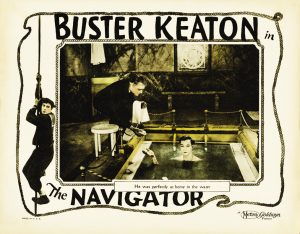

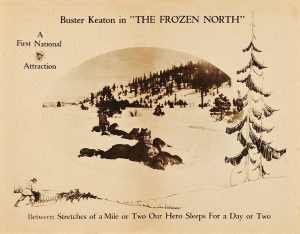

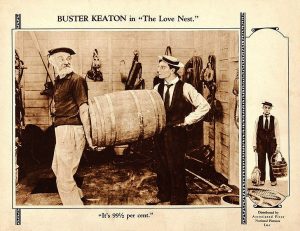

Buster made all of his silent era "Buster Keaton Comedies" from his studio as a base. All of them. Beginning with One Week through the classic Steamboat Bill, Jr. 29 features and shorts over a period of just under 9 years, from 1920 through 1928.

Keaton surrounded himself with a team of players, writers, and directors second to none. Joe Roberts was his frequent foil until his stroke and death in 1923. Roberts had been a family friend and appeared in more Buster Keaton movies than anyone except Buster himself. Eddie Cline wrote stories and helped Buster direct his movies and was Keaton's collaborator on two television series yers later. Friend Lex Neal was also a writer for Buster as was Clyde Bruckman. But Buster was always regarded (by his many admirers and competitors) as his best writer and director.

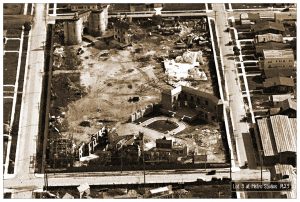

Metro Studios closed their Hollywood studio in 1924, and after the merging with Goldwyn moved all [production to the big Culver city studio they inherited. While the Hollywood studio lay derelict and falling apart, Buster was at the height of his career and continued making movies here at his very modest, very modern Buster Keaton Studio.

Most of Keaton's films are now considered classics and to this day is still considered one the (if not the) finest filmmakers of the silent era. The General, Sherlock, Jr., Our Hospitality, Seven Chances, Steamboat Bill, Jr are all considered masterpieces (as is his first at MGM, The Cameraman). Yet Buster would tell you that he was just having fun doing what he does best, making movies.

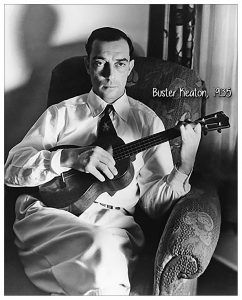

In 1928 Joseph Schenck talked Buster into signing with MGM, and he went to work in Culver City for Louis B. Mayer. The studio here was eventually sold to a radio station.

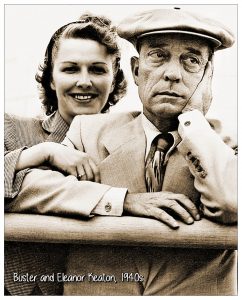

Buster's stay with MGM was relatively short, he did not get along with Louis B. Mayer, and lost control of his movies. His career went on the skids for a decade but, thanks to his new wife, Eleanor, he made a comeback and is regarded as a comedy genius, side-by-side with Charles Chapliun, Hrold Lloyd, and Laurel and Hardy.

Buster Makes a "Big Mistake"

Buster Keaton admits he made what was essentially a career-halting mistake. According to his autobiography, My World of Slapstick, he let Joseph Schenck talk him into signing a contract with MGM in 1928. Chaplin and Lloyd both tried talking him out of signing. They both understood the value of remaining independent and both profited from that. "Don't do it, Buster," Chaplin implored him.

He understood that, but Buster did not have the same business acumen as Lloyd and Chaplin, and In the end, he succumbed to Schenck's influence. Louis B. Mayer became his boss. It was never a good relationship and Buster began to devolve.

His mistake was not really signing with MGM. It was really that he did not control his movies. He did not own "Buster Keaton Comedies," someone else did. He did not own "Buster Keaton Studio, someone else did. He was allowed creative control, but was always an employee of someone else and subject to their approval. The pattern continued with MGM.

Harold, once he left Roach, owned his movie product and profited for decades from them. Charlie became his own boss after leaving First National. He bought a studio and became a partner in the iconic United Artists. Both understood business and surrounded themselves with good business advisors.

Admittedly, Buster was not a businessman. He had a contract with Schenck that made him rich, but no long term plan to secure it as wealth. Other people profited long-term from his labor long after he was fired by MGM and reduced to poverty. While Lloyd and Chaplin (and Pickford and Fairbanks, and other top stars) made money from their old movies and other investments (business, real estate, etc.), Buster could only get low-budget, low-paying work, as someone's employee.

All that said, if Buster had ownership of his movies, ownership of his studio, had made more movies under his own creative control, had long-lasting income for his efforts, had invested his money in other areas, there is one thing he probably would not have had. He probably would not have met Eleanor, the love of his life, and his emotional rock, and the engineer of his successful comeback. In the end, Buster Keaton lived a comfortable, modest life surrounded by people that loved him.

I would be willing to bet that Buster Keaton was far happier having traded life-long wealth for life-long love.

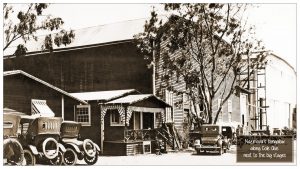

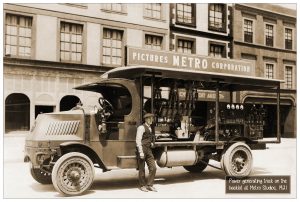

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

Metro-Goldwyn Pictures

Metro-Goldwyn

6100 Romain

1924

10202 Washington Blvd

1924-

While Metro prospered, across town in Culver City Goldwyn Pictures struggled. While Metro was bursting at the seems for more studio space, Goldwyn rattled around in the industry's largest studio with room to spare. While on a trip to Florida in December of 1923 a chance meeting happened between the heads of the two studios and a merger deal was set in motion. On April 18, 1924, the merger was consummated.

This proved to be a huge deal, one to rival the Paramount and Universal conglomerates. Soon after the merger, the Mayer name was added to the moniker creating what would be, for years and decades, Hollywood's largest motion picture company and largest studio complex.

After the merger, the Metro side wasted no time moving its company to the Goldwyn studio. They finished up the movies that were currently in production and the final film, Jackie Coogan’s Little Robinson Crusoe which wrapped in July, and the studio was finally closed, and lay abandoned for another half-decade before being torn down and sold off.

Buster Keaton continued production at his little studio until 1928.

Additional research courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives