What Might Have Been

The Poverty Row Studio that Behaved Like a Major

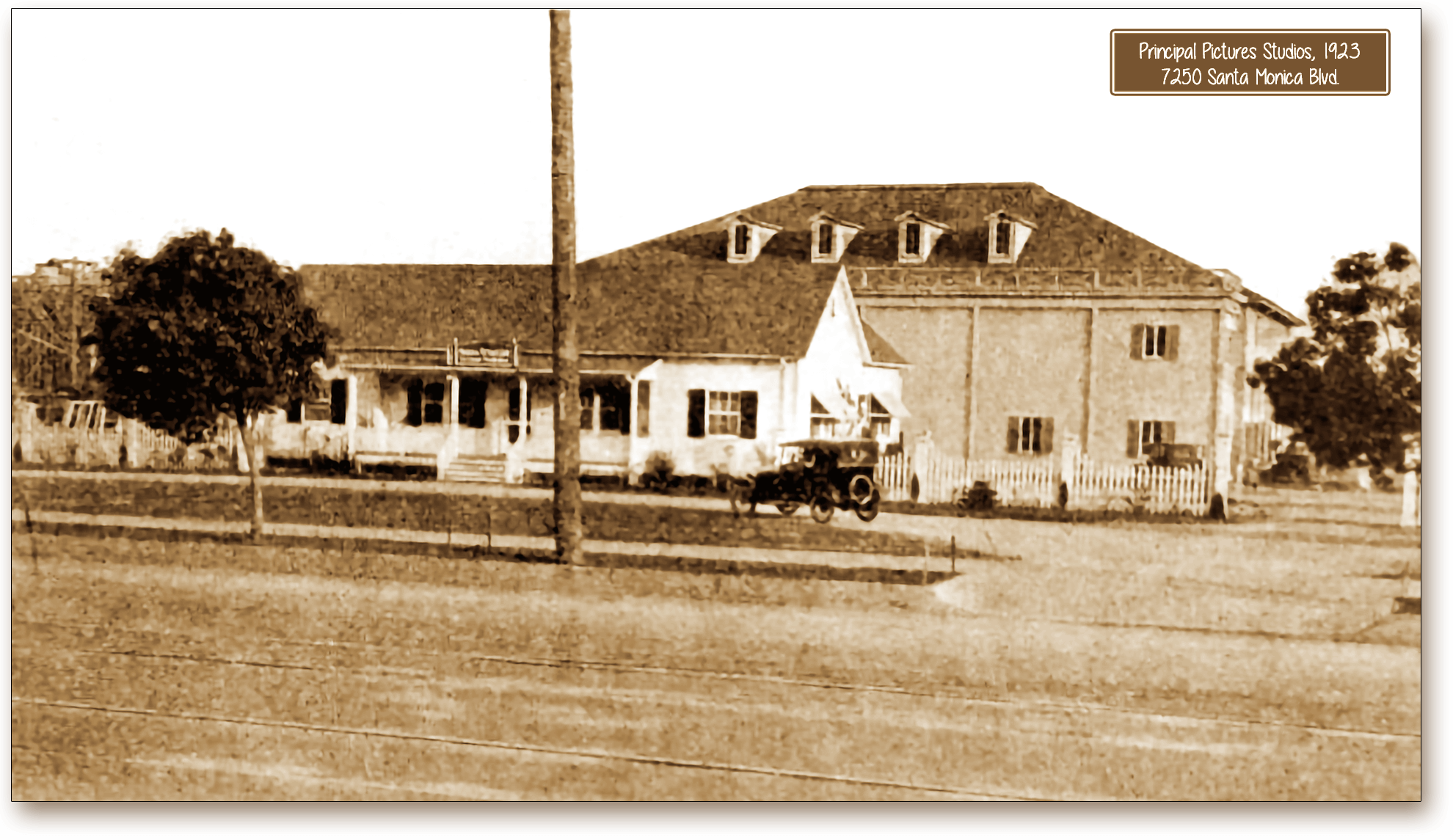

7250 Santa Monica Blvd.

This small lot, built into a very fine studio over the years suffered a fate different than its neighbors. It could have ended up a major rental lot, like Hollywood Studios, or even a mini-major, like RKO. But instead, a series of underfunded minor producers bought and sold the studio allowing it to be run into the ground until it was sold to a developer and became a mini-mall and condo complex. Oh, what might have been!

Related Pages:

Read More:

Vidor Village

The King Vidor Studio

7250 Santa Monica Blvd.

1920-1922

King W. Vidor was coming into his own, on his way to a stellar career equal to that of John Ford, Cecil B. DeMille, William Wellman, Billy Wilder, or Frank Capra when he bought about 4 acres on Santa Monica Blvd.

Vidor was born in Galveston, Texas February 8, 1894, and lived through the devastating Galveston hurricane of 1900. He started his career filming The Hurricane in Galveston, in 1913, a documentary of a different Hurricane. He is best remembered for his silent masterpieces, The Big Parade (1925), and The Crowd (1928), the masterpiece Stella Dallas starring Barbara Stanwyck (1937), and his seminal sound masterpiece Duel in the Sun (1946). He was a Hollywood pioneer and a 5 time Oscar nominee.

click to enlarge

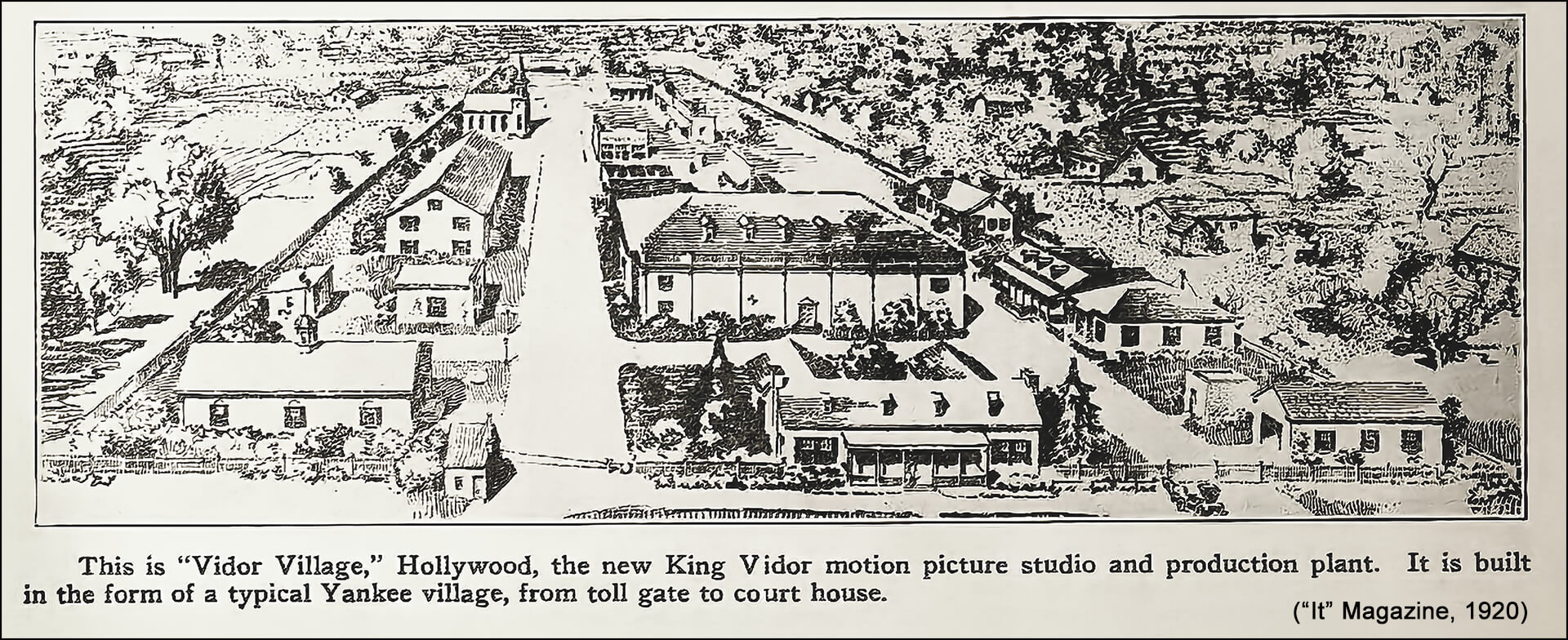

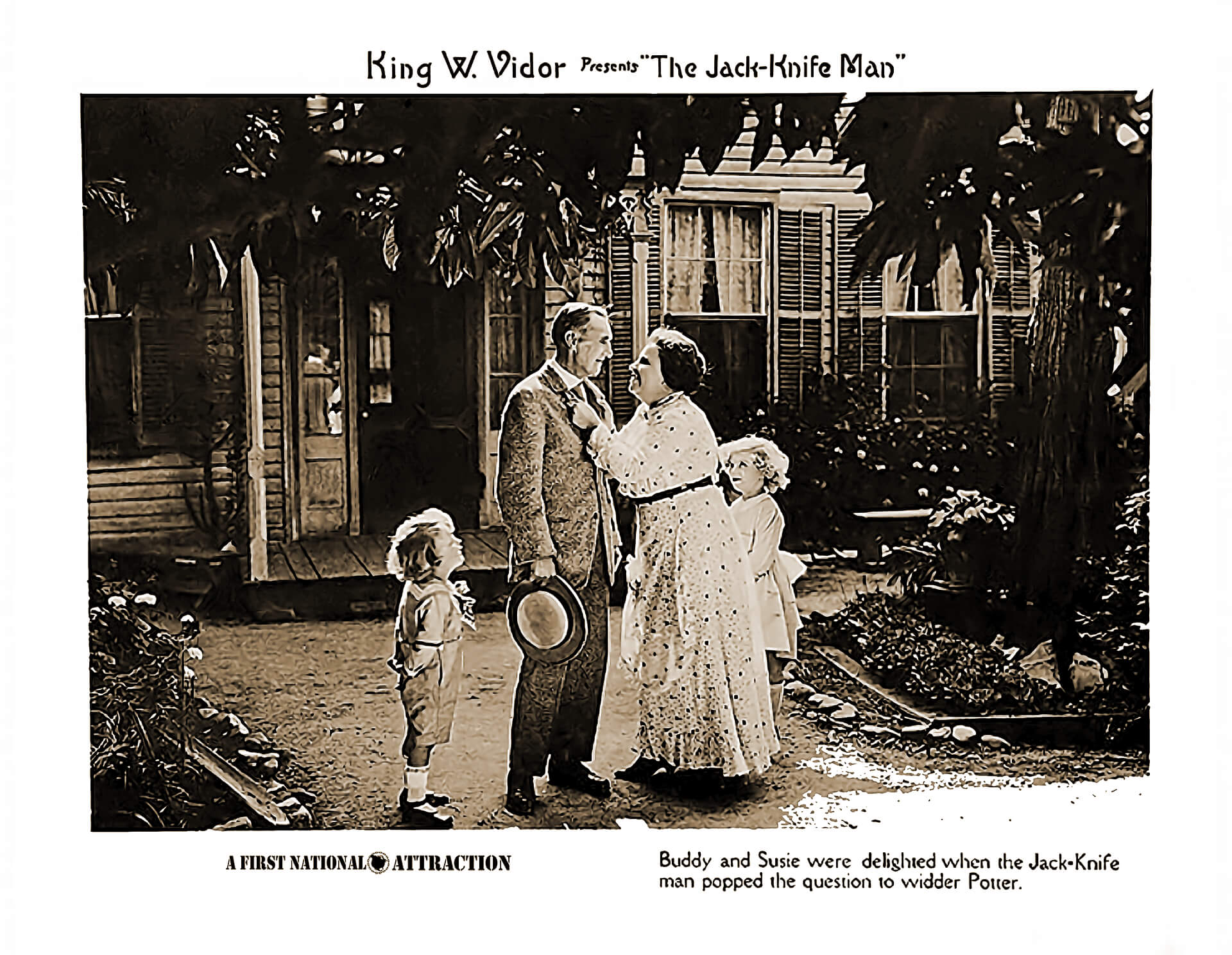

In 1920, with financial backing from his father, the ambitious Vidor built and ran "Vidor Village," a small studio where he directed eight movies over the next 3 years, many of them starring his wife, but the marriage hit problems and the couple separated in 1923, divorcing a year later.

After his early successes, Vidor, who is considered an "auteur" style director (one who often writes, produces, and directs his pictures) thought it might be time to build his own base of operations. In 1919 he bought roughly 13.5 acres (disputed) at 7250 Santa Monica, right next door to Jesse Hampton's new studio (which later became the iconic Pickford-Fairbanks/United Artists Studio). He dubbed the new studio Vidor Village.

The Village consisted of an administration building and a large glass stage (75 ft. x 150 ft.), plus two streets of outdoor sets that resembled any Americana town that also doubled as offices, dressing rooms, prop rooms, carpentry shops, plus provided housing for any employee who needed it. Here Vidor could shoot virtually any indoor or outdoor scene his films needed. The studio manager has Vidor's father, Charles S. Vidor. With a distribution contract with First National Exhibitors Vidor began shooting films of "simplicity, charm, and naturalness."

Vidor was a gentle, smiling, calm man. A Christian Scientist. He always concerned himself with the comfort of those around him, taking great pains to make sure everyone had enough to eat and a place to sleep.

His philosophy was that of an artist, not a movie maker. "'Hurry is a disease. It is confusion, noise. It forgets dignity and that all things should be done decently and in order. It pays no attention to appearances or to the comfort of others. It has no time to be pitiful or courteous. All it has is speed. It often forgets the object it had in view."

King Vidor owned his little unique studio for only two years, and during that time produced and directed only 7 films. Cost overruns on this film The Sky Pilot, caused Vidor Productions to go into financial distress and to avoid bankruptcy King Vidor sold his Vidor Village and shut downVidor productions.

Vidor sold his little studio to Sol Lesser's Principal Pictures Corp. at the end of1922 and signed a contract with Metro Pictures, the behemoth studio just down the block, to produce and direct. When Metro merged with Goldwyn Pictures Vidor moved with the company to Culver City producing for both Metro and Goldwyn while their merger was in progress. He stayed with the merged M-G-M for 20 years working intermittently for independent producers like Samuel Goldwyn and David O. Selznick, before once again, returning to independent work.

King Wallis Vidor died November 1, 1982, at his home in Paso Robles, California. His little studio survived until 1960.

Did King Vidor solve Hollywood's

most infamous murder?

In the Sidney Kirkpatrick book, A Cast of Killers, King Vidor conducted an investigation into the murder of his contemporary director, William Desmond Taylor who was shot and killed in his home in February 1922. At the time of his death, the 49-year-old Taylor was having major success and was on the verge of becoming a giant among directors, alongside Griffith, DeMille, Ford, Ince, and others, including Vidor himself.

This was Hollywood's biggest scandal and alongside the Roscoe Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, Olive Thomas, and Wallace Reid sandals created a loathing of the "Hollywood" lifestyle among the church-going public, and studios began imposing a "morality clause" in every Star and studio employee contract, eventually leading to the "Production Code" dictating to filmmakers what they could and could not show on the screen.

Vidor, attempting to rekindle his flagging career decided, with the help of long-time friend Colleen Moore, to produce and direct a film on the death of Taylor. He began researching ideas for the script. But he knew that in order to make the film he envisioned, he would need to know who Taylor's killer was. Over a six-month period in 1967, he began what he thought would be a standard movie research project but everywhere he turned he ran into walls, half-truths, and downright deception. It was clear that evidence had been covered up, tampered with, and destroyed. The killer was actually known by authorities, but a big silence was taking place. Why? He needed to uncover the truth.

King Vidor's research, which turned into a substantial criminal investigation, was shared with writer Sidney Kirkpatrick after Vidor's death by his estate. Kirkpatrick weaves Vidor's notes, interviews, and conclusions into a narrative that reads like a well-honed novel. It tracks the death of Mr. Taylor and the involvement of various Hollywood stars and studio executives and personnel, the LAPD, and Los Angeles D.A.'s office, and reveals a general coverup of the evidence. Through interviewing the people involved, each of whom reveals a few more facts, and digging through archive records and press accounts, Vidor finally is able to put all the pieces together and reveal the truth, known at the time but hidden from the public and the system. He discovered William Desmond Taylor's killer.

In a very touching sub-plot, King Vidor and Colleen Moore rekindle a romance after not seeing one another for over 40 years. Both are married and they do not violate their vows. A very affectionate and tender picture of them is painted.

To find out what King Vidor discovered, the book is a riveting and quick read.

Sol Lesser's Principal Pictures Studios

7250 Santa Monica Blvd.

1922-1925

At the end of 1922, Vidor sold his little studio to Sol Lesser for his Principal Pictures Corporation. Lesser was a well-established independent producer with several films already under his belt. At the age of 32, when Lesser bought the studio, he was considered a "boy wonder" because of his continued successes in starting companies, including distributors First National and All-Star Features, as well as chains of theaters, plus buying the rights to movies and stars and shepherding them to financial success.

Lesser had produced the novels of Howard Bell Wright and had signed to produce the screen versions of plays by George M. Cohan. He immediately placed three stars under contract: Baby Peggy, Jackie Coogan, and silent star Harry Langdon, and others including Blanche Sweet and Bert Lytell. With Coogan, he made Oliver Twist, a tremendous financial success, and with Baby Peggy, he made Captain January.

Lesser had big plans to update and expand the studio, but with the exception of adding a stage, those plans never materialized. He struck a deal to relocate Principal Pictures to the United Studios on Melrose (the future Paramount studio), where a new wing of offices and stages were built for his use. In 1924 he sold the studio to Earle Hammons for his Educational Pictures and in the spring of 1925, the Principal's new facilities were ready to move into, and Hammons took over.

Additional reading at Wikipedia

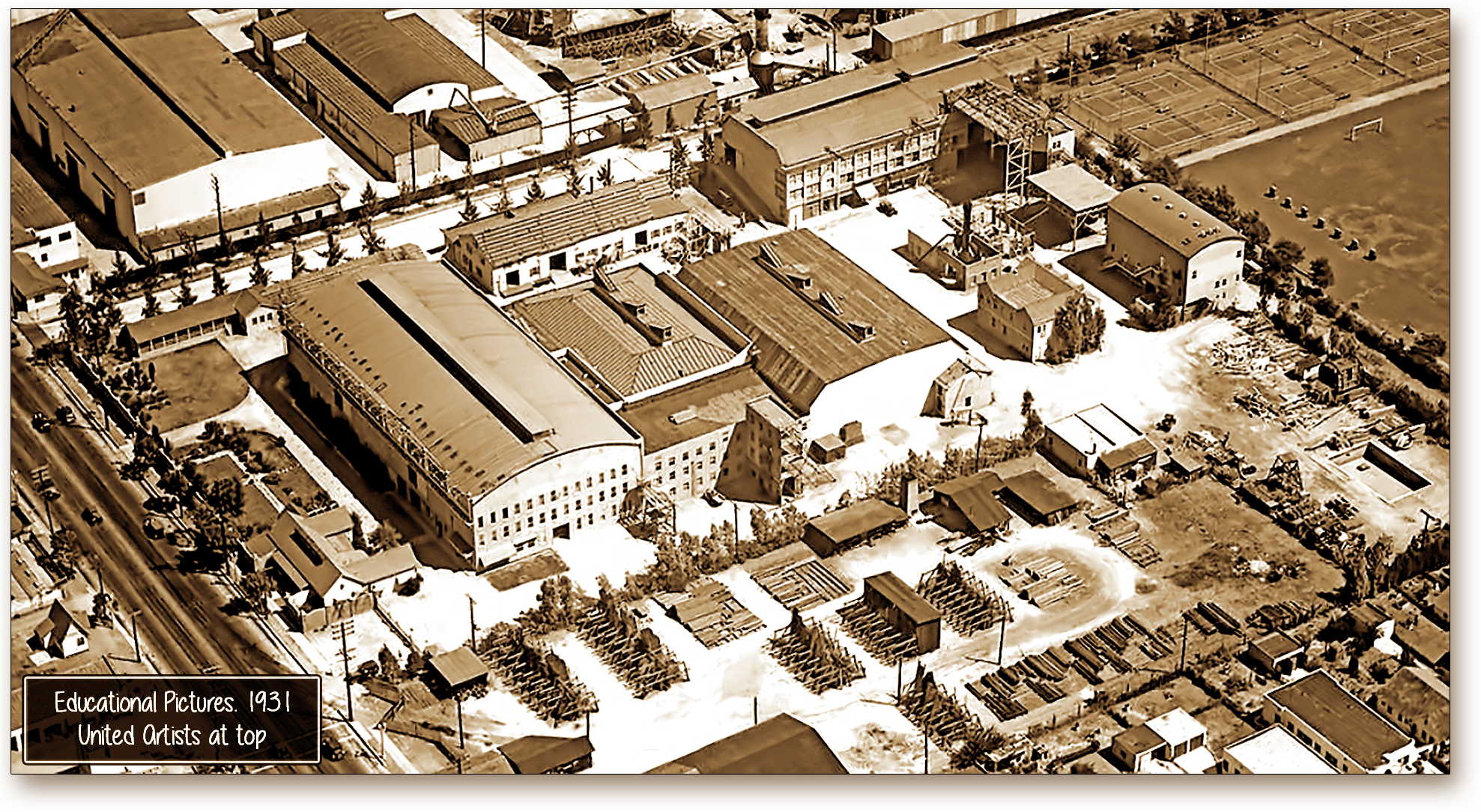

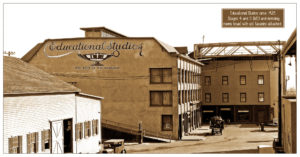

Educational Pictures Studios

Educational Films Corporation of America

7250 Santa Monica Blvd.

1924(5)-1937(8)

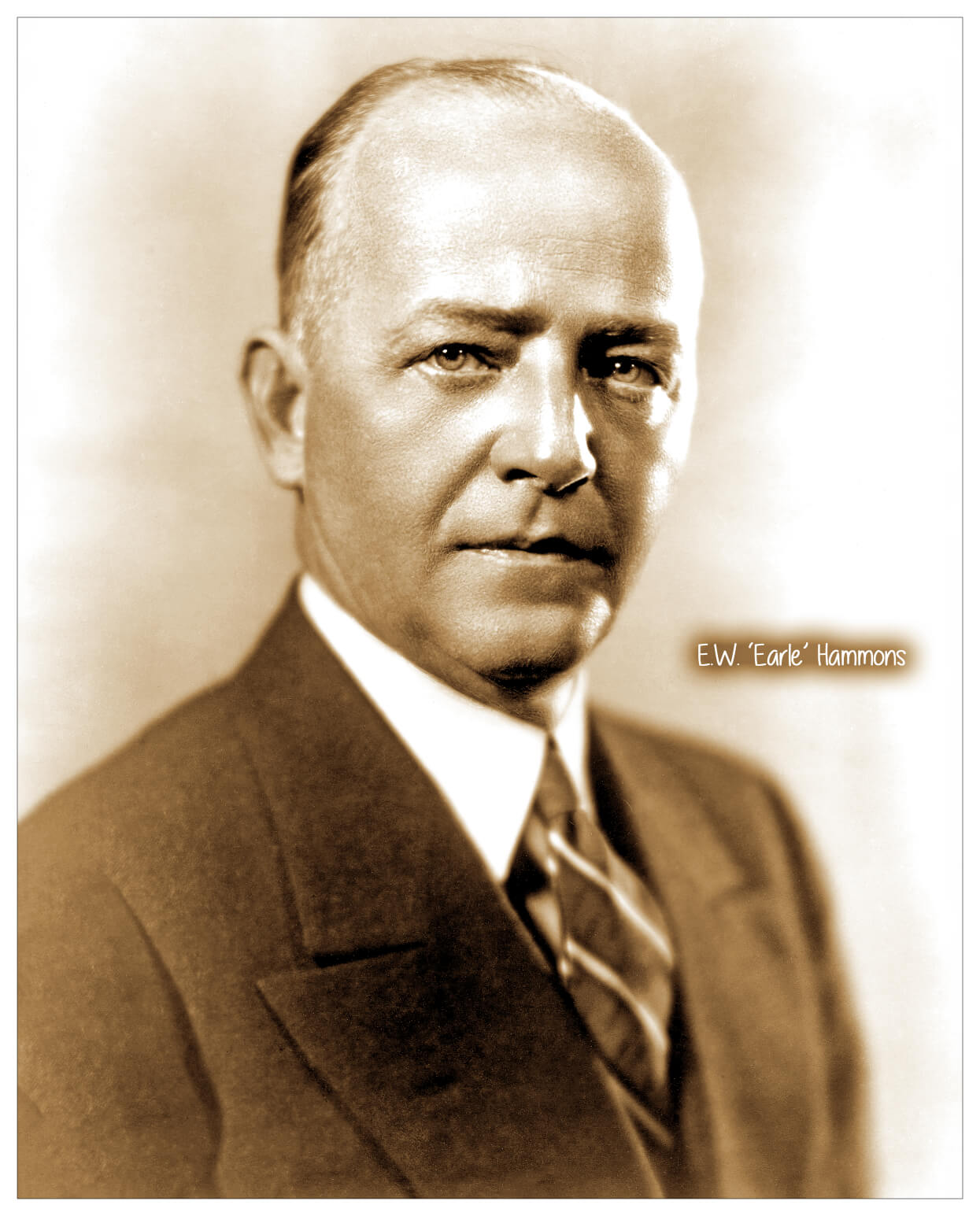

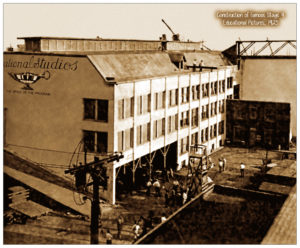

E. W. (Earle) Hammons and his Educational Pictures bought the studio in late 1924 from Sol Lesser for $250,000 and began a massive $100,000 expansion program covering nearly every inch of the lot. He moved the company into their new home moved in the spring of 1925.

Educational Pictures began in 1915 as a distributor of, you guessed it, instructional films for schools. In 1919 he transitioned to the distribution documentaries and travelogues and in 1920 to the much more profitable short subjects, primarily comedies eventually getting into feature films. Before buying the lot from Principal, Educational leased a variety of studios and stages around Hollywood and New York.

Earle Hammons, president of Educational

click to enlarge

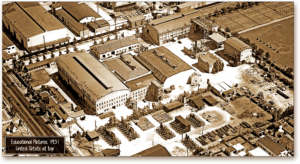

After the purchase, Hammons quickly built four new stages, including the iconic Stage 4, an 80 x 100-foot stage built as the second story above the scene dock. When the new big stage building (stages 6 & 7) was constructed in 1926 between King Vidor's original stage, the little house that Vidor built for the studio's offices, the house was moved about 100 feet to the west to make room. Producer's bungalows, office buildings, dressing rooms, carpentry shops, prop, wardrobe, and electrical departments, cutting and projection rooms were constructed. A number of standing sets were erecting and several facades were attached to buildings across the lot. They even built a water tank.

Educational was as complete and modern a studio as could be found in the country.

By 1926 most of the comedy units, both owned by Hammons and distributed by Educational, had moved onto the lot, consolidating most of their efforts in one location.

Educational's production units included Lupino Lane Comedies, Hamilton Comedies, Big-Boy Juvenile comedies, Dorothy Devore comedies, Larry Semon Comedies, Tuxedo Comedies, Mermaid Comedies, Cameo Comedies, Lyman H. Howe’s Hodge-Podge comedies, Felix the Cat Cartoons, Carter De Haven Character Studies, Outdoor Sketches, Curiosities with Walter Futter, Bowers Comedies, and Kinograms.

In roughly 1927 a merger, or more properly an affiliation or what we would call today a "strategic partnership," was arranged between Educational and the Christies Brothers Metropolitan Studios, down the block at Santa Monica and Las Palmas. They both were managed by AT&T's General Service Company using AT&T's Western Electric sound system anticipating the coming sound era. General Service eventually bought out Metropolitan and owned the studio for many years (read more here).

Hammons' biggest stars included Buster Keaton after his firing from MGM, Shirley Temple before her fame at Fox, James Cagney when he was fighting with Warner Bros. Other stars included Boris Karloff when his Universal star began to fade, Harry Langdon during his talkie days, and Roscoe Arbuckle who directed for Educational after the scandal that ended his acting fame.

Educational's reputation was on the rise as evidenced by other Educational stars which included Bing Crosby, Edward Everett Horton, Al St. John, Lloyd Hamilton, Louise Brooks, Vernon Dent, Andy Clyde, Bob Hope, The Ritz Brothers, Shemp Howard, Joan Davis, Billy Gilbert, Imogene Coca, June Allyson, Bert Lahr, and Danny Kaye. In 1930, mega-mogul Mack Sennett began distributing his comedies through Educational.

Hammons produced nearly 500 movies between 1916 and 1939. While some were produced at Paramount's Astoria studio in New York (and elsewhere) the majority of them were shot here, at 7250 Santa Monica Blvd., in Hollywood. These Hammons-produced films were included in the nearly 2,000 films distributed by the Educational Film Exchange.

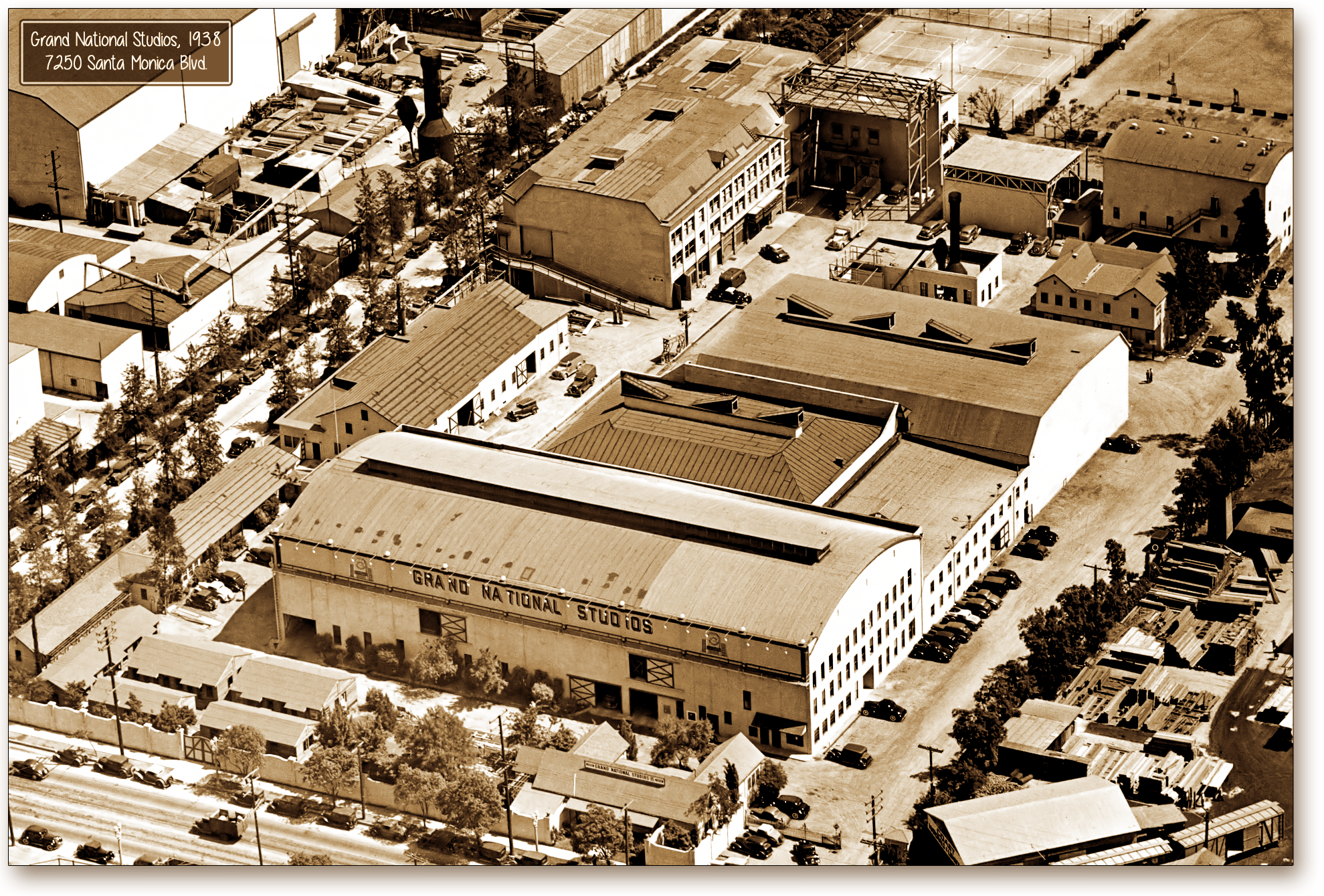

Grand National Studios

7250 Santa Monica Blvd.

1937(8)-

E. W. (Earle) Hammons and his Educational Pictures bought the studio in late 1924 from Sol Lesser for $250,000 and began a massive $100,000 expansion program covering nearly every inch of the lot. He moved the company into their new home moved in the spring of 1925.

Educational Pictures began in 1915 as a distributor of, you guessed it, instructional films for schools. In 1919 he transitioned to the distribution documentaries and travelogues and in 1920 to the much more profitable short subjects, primarily comedies eventually getting into feature films. Before buying the lot from Principal, Educational leased a variety of studios and stages around Hollywood and New York.

Tex Ritter, Conrad Nagel, James Cagney, Neil Hamilton, Stuart Erwin, Wallace Ford, Leon Aames, Al St. John, George Houston, Lupe Velez, Rod La Rocque, Hobart Bosworth, Betty Compson, Ken Maynard, Sally Rand, Toby Wing, Grant Withers, Leonid Kinski, Anna Sten, Ben Lyon, James Mason, Dorothy Page, Gilbert Roland, Katherine DeMille, Harry Langdon