Related Pages:

Read More:

King Wallis Vidor was a successful and arguably legendary producer and director whose career spanned both the silent and the sound eras.

His professional filmmaking career began in 1913 with the production of Hurricane in Galveston, a short documentary. His last feature was Solomon and Sheba in 1959. and his final film, The Metaphore (a short documentary), was produced in 1980. His career spanned 67 years.

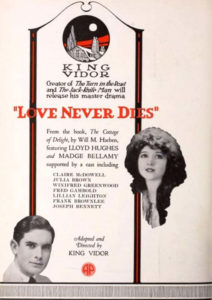

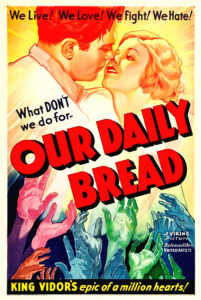

Vidor's early career was marked by films tackling tough social issues, particularly those of the disenfranchised and struggling. He took on racial issues, family issues, economic injustice, poverty, and class struggles. During the sound period, his libertarianism created films around the themes of individualism, defiance, and overreach.

Early Life

King Vidor was born in Galveston, Texas February 8, 1894. His father, Charles, was a successful lumber mill operator and King's childhood was filled with abundance. At the age of six he witnesses and survived the devastating Galveston hurricane that destroyed and leveled most of his hometown and killed thousands of ill-prepared residents.

From an early age, King Vidor had a camera in his hand and he took photos everywhere he went.

Vidor was raised as a Christian Scientist, which shaped his life and career, and gave him a moral "metaphysical" base philosophy.

Early Career.

His earliest job was as a ticket taker and projectionist at a local theater, where he proved an astute student, watching the movies with the goal of learning how films were made and put together to achieve dramatic effect.

In 1913 Vidor began filming short newsreels with his partner and fellow Hollywood aspirant, Edward Sedgewick. The first two were The Grand Military Parade and Hurricane in Galveston.

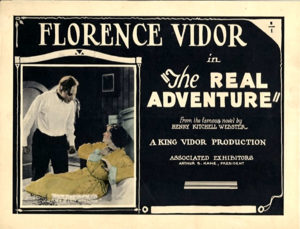

In 1915 Vidor married his girlfriend, Florence Arto, who when on to her own long career as a popular actress Florence Vidor, even after their 1924 divorce. The newlyweds move to the Los Angeles area where King spent the better part of 1918 directing 16 shorts for Judge Willis Brown's Boy City Film Corp. of Culver City, morality plays about juvenile delinquency and racial discrimination.

King Vidor's greater ambitions

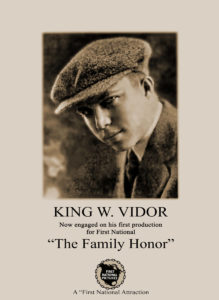

In 1919 King Vidor directed his first feature film, The Turn in the Road for Famous Players-Lasky at their Vine Street studio. Then he had a short stint with Brentwood Pictures on Fountain Street directing his wife, Florence, in several films, and discovered the struggling comic actress, Zasu Pitts putting her in her first feature. After a few individual projects for Vitagraph, Universal, and Famous Players-Lasky, he thought he was ready for the big time. He was so right.

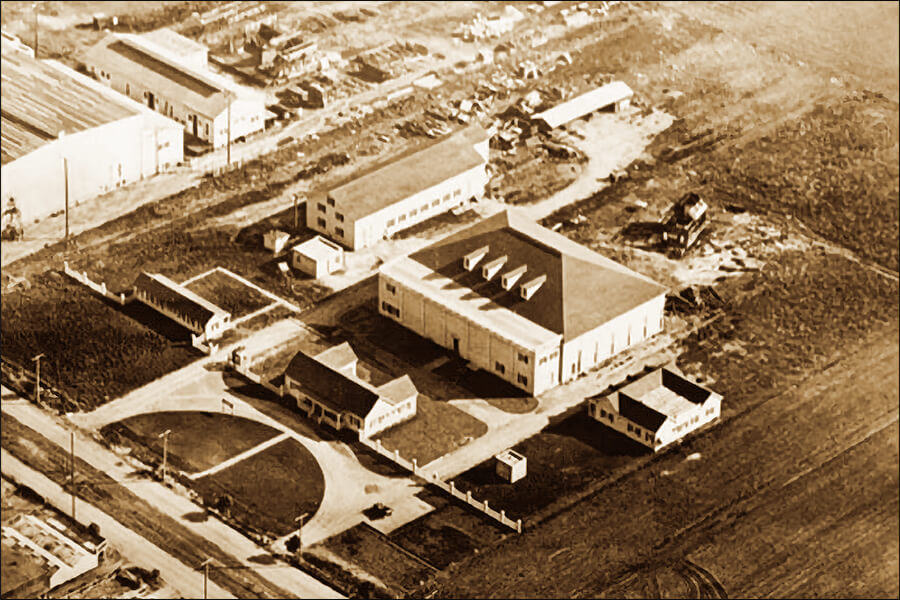

He builds a studio

In 1920, with financial backing from his father, the ambitious King Vidor built and ran "Vidor Village," a small studio where he directed seven movies over the next 2 years. His father, Charles S. Vidor, was the studio's manager while King went about the business of making movies, many starring his wife, Florence.

After his early successes, Vidor, who is considered an "auteur" style director (one who often writes, produces, and directs his pictures) thought it might be time to build his own base of operations. In 1919 he bought 4 acres (disputed) at 7250 Santa Monica, right next door to Jesse Hampton's new studio (which later became the iconic Pickford-Fairbanks/United Artists Studio). He dubbed the new studio Vidor Village.

The Village consisted of an administration building and a large glass stage (75 ft. x 150 ft.), plus two streets of outdoor sets that resembled any Americana town that also doubled as offices, dressing rooms, prop rooms, carpentry shops, plus provided housing for any employee who needed it. Here Vidor could shoot virtually any indoor or outdoor scene his films needed. With a distribution contract with First National Exhibitors Vidor began shooting films of "simplicity, charm, and naturalness."

Vidor was a gentle, smiling, calm man. A Christian Scientist. He always concerned himself with the comfort of those around him, taking great pains to make sure everyone had enough to eat and a place to sleep.

His philosophy was that of an artist, not a movie maker. "'Hurry is a disease. It is confusion, noise. It forgets dignity and that all things should be done decently and in order. It pays no attention to appearances or to the comfort of others. It has no time to be pitiful or courteous. All it has is speed. It often forgets the object it had in view."

King Vidor owned his little unique "Americana" style studio for only two years, and during that time produced and directed only seven films.

Vidor sells Vidor Village.

His success as a studio owner was short-lived, and the costs of running it ate into the small profits he made from the distribution of his movies. His biggest movie of the era, Sky Pilot, did poorly at the box office, and rather than file for bankruptcy, he decided to sell his little village.

He sold his little studio to Sol Lesser's Principal Pictures Corp. at the end of 1922 and signed a contract with Metro Pictures, the behemoth studio just down the block, to produce and direct.

Vidor's M-G-M years

When Metro merged with Goldwyn Pictures Vidor moved with the company to Culver City producing for both the Metro and Goldwyn units while their merger was in progress. Vidor stayed with M-G-M for 22 years while working intermittently for independent producers Goldwyn (who would allow him to make pictures his way), David O. Selznick (who never allowed anyone to make movies except in the Selznick way), and a short stint with Warner Bros. In the 1950s, he once again became an independent working for himself and based at his Paso Robles, CA home.

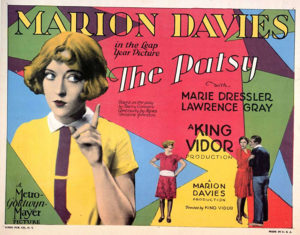

Meanwhile, in 1926 Vidor married actress Eleanor Boardman. The marriage lasted until 1933, then he married non-actress Elizabeth Hill, a marriage that lasted the rest of his life.

King Vidor the Auteur

Vidor's heyday was the period from the mid-1920s to the mid-1940s when he produced not only box office hits but had his greatest successes as an artist. He was a true Auteur, frequently producing, writing, and directing his films. His vision and storytelling were legendary, and his ability to capture the imagination of the movie-going public was second to none.

His list of great movies put him in the pantheon of great filmmakers, yet one wonders why he is not remembered in the same way his contemporaries were. John Ford, DW Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, Thomas Ince, Frank Capra, William Wellman, Billy Wilder are all well remembered and highly regarded, where King Vidor history has related King Vidor to the shadows.

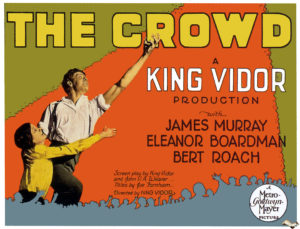

During the silent period, Vidor produced two arguable masterpieces: The Crowd in 1928, for which he got his first Best Director nomination and starring wife Eleanor Boardman about the misery and humdrum of middle-class life. And, the biggest box office success to that time, The Big Parade (1925) with legend John Gilbert, Renée Adorée, and Hobart Bosworth about the horrors of war viewed through the eyes of one soldier.

The transition to talkies

Vidor made it easily. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he seamlessly made the transition simply looked at it as a new challenge. So involved with the new technology, he actually invented the boom mic, which allowed actors to move around the set without going out of mic range.

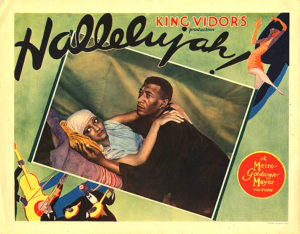

KIng Vidor's success in the sound era in many ways surpassed his silent accomplishments. His first "talkie" was Hallelujah (1929) about racial injustice. It featured Hollywood's first all-black cast and garnered Vidor his second Best Director nomination.

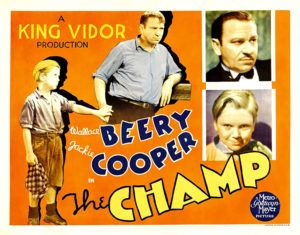

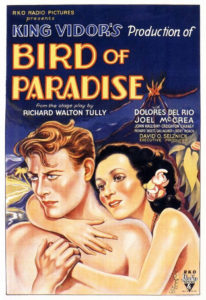

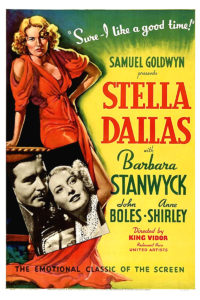

The 1930s and 1940s were King Vidor's most prolific period. He worked with many of Hollywood's top stars and produced some of its biggest hits. He produced and directed the box office hits Stella Dallas (1937) starring Barbara Stanwyck and 1938's The Citadel starring Robert Donal, shot at M-G-M's British studio, receiving several Oscar nominations. And King Vidor directed Noah Beery to an Oscar for his performance in The Champ (1931).

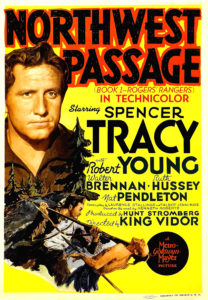

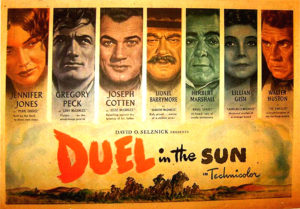

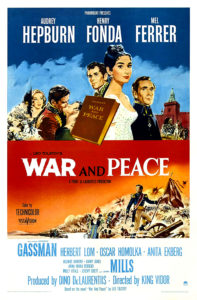

He directed (uncredited) the tornado scene in The Wizard of Oz (1939)including all of the Kansas black and white scenes, as well as the tornado. He directed Spencer Tracy in 1940's hugely popular Northwest Passage, and Clark Gable and Hedy LaMarr in the satire Comrade X also in 1940. In an attempt to recreate the success and grandeur of Gone with the Wind, David Selznick hired Vidor in 1947 to direct Selznick's wife Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun also starring Gregory Peck and Joseph Cotton. That was followed by Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead in 1949 with Gary Cooper and newcomer Patricia Neal. The 1950s saw spectacles War and Peace (1956) with Henry Fonda and Audrey Hepburn, followed by Solomon and Sheba with Yul Brynner and Gina Lollobrigida in 1959.

Did King Vidor solve Hollywood's

most infamous murder?

In the Sidney Kirkpatrick book, A Cast of Killers, King Vidor conducted an investigation into the murder of his contemporary director, William Desmond Taylor who was shot and killed in his home in February 1922. At the time of his death, the 49-year-old Taylor was having major success and was on the verge of becoming a giant among directors, alongside Griffith, DeMille, Ford, Ince, and others, including Vidor himself.

This was Hollywood's biggest scandal and alongside the Roscoe Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, Olive Thomas, and Wallace Reid sandals created a loathing of the "Hollywood" lifestyle among the church-going public, and studios began imposing a "morality clause" in every Star and studio employee contract, eventually leading to the "Production Code" dictating to filmmakers what they could and could not show on the screen.

Vidor, attempting to rekindle his flagging career decided, with the help of long-time friend Colleen Moore, to produce and direct a film on the death of Taylor. He began researching ideas for the script. But he knew that in order to make the film he envisioned, he would need to know who Taylor's killer was. Over a six-month period in 1967, he began what he thought would be a standard movie research project but everywhere he turned he ran into walls, half-truths, and downright deception. It was clear that evidence had been covered up, tampered with, and destroyed. The killer was actually known by authorities, but a big silence was taking place. Why? He needed to uncover the truth.

King Vidor's research, which turned into a substantial criminal investigation, was shared with writer Sidney Kirkpatrick after Vidor's death by his estate. Kirkpatrick weaves Vidor's notes, interviews, and conclusions into a narrative that reads like a well-honed novel. It tracks the death of Mr. Taylor and the involvement of various Hollywood stars and studio executives and personnel, the LAPD, and Los Angeles D.A.'s office, and reveals a general coverup of the evidence. Through interviewing the people involved, each of whom reveals a few more facts, and digging through archive records and press accounts, Vidor finally is able to put all the pieces together and reveal the truth, known at the time but hidden from the public and the system. He discovered William Desmond Taylor's killer.

In a very touching sub-plot, King Vidor and Colleen Moore rekindle a romance after not seeing one another for over 40 years. Both are married and they do not violate their vows. A very affectionate and tender picture of them is painted.

To find out what King Vidor discovered, the book is a riveting and quick read.

King Vidor's personal life

Born in Galveston, Texas in 1894, Vidor lived a rather ieealic childhood. His father, Charles Shelton Vidor, a local lumber baron, provide King with all the comforts a child could want.

Young King, at the age of 6, was a witness of the Galveston hurricane and flood, a natural disaster that leveled the city of Galveston and killed nearly one out of every four Galveston residents.

He was raised by his mother as a Christian Scientist, a religion grounded in metaphysics, and provided him with a philosophical grounding that he used in his daily life. He described it in a documentary he produced in 1980, The Metaphore, his last film.

He married his childhood sweetheart, Florence Arto, in 1915 and the two began an odyssey that saw them move to Hollywood and become stars in the movie business. They had a daughter, Suzanne, who was born in 1903 and lived for 90 years. The Vidors divorced in 1926, but remained friends for the rest of their lives.

In 1921, when he owned Vidor Village, he produced a movie called Sky Pilot. The company spent a considerable amount of time on location, in Truckee, California, shooting the outdoor scenes. King Vidor met and fell in love with a young actress, Colleen Moore. They had a three-year relationship, described as "Hollywood Legend." but as both were already involved, they ended the romance vowing to never see one another again. A vow they kept for more than 40 years. But they always carried a very hot torch for each other, that impacted their lives and relationships. If there are "soul mates" King Vidor and Colleen Moore were certainly that. Or perhaps "the one who got away."

Though she never knew about King's feelings for Miss Moore, it caused a rift in his marriage to Florence, his childhood sweetheart. The Vidors separated in 1923, divorcing a year later. Florence went on to her own very successful career and future marriage to famed violinist Jascha Heifetz.

In 1926 Vidor married actress Eleanor Boardman, a marriage that lasted until 1933. They had no children.

In 1937, King Vidor married Elizabeth Hill ("Betty"), who was not in the industry. Though they were married until King's death in 1982, it was not the kind of deeply fulfilling marriage that both wanted. They began to grow apart in the 1950s. King moved out of the main house into his office in eventually moving to his beloved Willow Creek Ranch in Paso Robles, California. Betty kept their Beverly Hills home.

King Vidor and Colleen Moore met again in 1967, as Vidor began research on his next movie. They grew very (very) close, and saw one another as frequently as they could.

King Vidor's legacy

King Vidor was considered an "actor's director." He knew how to motivate actors and let several actors to Academy Awards and nominations.

Vidor's early films dealt with human plight: struggles of the common man, poverty, job exploitation, racial injustice. His later films dealt with libertarianism and the "rugged individual." He produced many films that gained Oscar nominations for Best Picture.

Though he never won an Oscar, he did have five nominations and received a lifetime achievement honorary Oscar in 1979.

King Vidor died November 1, 1982, at his home in Paso Robles, California. Colleen Moore died six years later at her Paso Robles home, just down the road from Vidor's.