The studios of Adolph Zukor

26th Street, NYC

56th St. NYC

Hollywood's most powerful mogul

Adolph Zukor

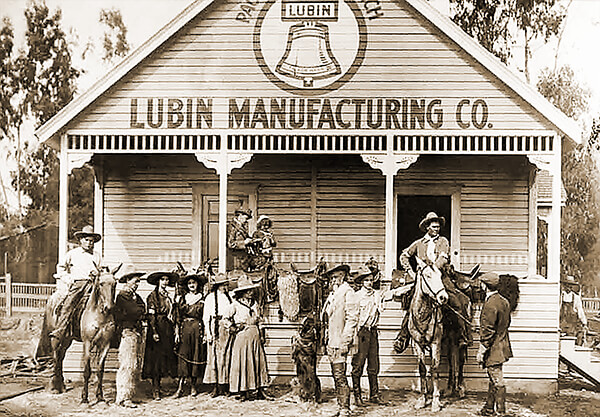

Sigmund Lubin

(click to enlarge)

Related Pages:

- Lubin Mfg. Co. main page

- Lubin's Pennsylvania studios

- Lubin's California Studios

- The Moguls main page

Adolph Zukor

As radical as Selznick was at what he was doing, Adolph Zukor was equally as radical with his business style. Zukor accumulated companies and studios. He didn't acquire them to own more things, but because of what their star power meant. Having things only made sense if they came with the power to make money with them. His aim was less become the largest in the industry, and more to be the most powerful and profitable.

As radical as Selznick was at what he was doing, Adolph Zukor was equally as radical with his business style. Zukor accumulated companies, studios, and star contracts. Not because he wanted stuff, but because of the power it represented, the control he gained, the profits it represented. While most early Moguls made emotional decisions (including Selznick) Zukor was quite cold and calculating in his decision making. Having things only made sense if they could help move him forward in the accumulation of power and control.

By the late teens, he had six companies and brands, and five studios (four large west coast plants, and the largest on the east coast). But more importantly, he controlled the biggest stars and directors in the business-the ones who brought in the most ticket sales and commanded the highest ticket prices. His had become the largest organization in the business.

The rest of the industry looked at Zukor and his ruthless style with suspicion and derision. He really didn't care who he had to step on to achieve his goals. His ego was as big as Selznick's. But where Selznick operated in the face of the industry, Zukor preferred to remain in the background and operate with stealth. Selznick and Zukor they fiercely disliked one another. Selznick never missed an opportunity to poke a finger at Zukor, in private or more often in the press.

By the late teens, he had five studios, four large west coast plants, and the largest on the east coast. But more importantly, he controlled the biggest stars and directors in the business-the ones who brought in the mist ticket sales and commanded higher ticket prices. He ran five companies, not yet merging them all together, which might have been an anti-trust violation, but running them as separate independent entities. Later he would merge them into one entity, Famous-Lasky-Paramount, and in the 1930s he would change the name to Paramount Pictures. He had become the largest organization in the business.

Direct quote from the book

Under the Paramount system, Mary Pickford's pictures had earned in the United States rentals of approximately $100,000 to $125,000 each. Under the Artcraft system the prices were, broadly stated, trebled at the start, so that her films would yield $300,000 or more each in this country alone. As soon as information regarding these rental scales reached the exhibitors, they loudly condemned Zukor, alleging intent to monopolize stars, annihilate competition, treble picture prices, and swallow the industry. Apparently nothing would satisfy them but a general movement of theater owners to discipline Zukor rigorously before he could become more powerful. Such action was not practicable. Zukor was saved by the inability of exhibitors to get together among themselves and decide on anything. Twelve to fourteen thousand active, aggressive retailers, each an ardent individualist, could not instantly abandon life-long habits of independent thought and action and join in a co-operative movement. There was a great deal of excoriation of Zukor, but Al Lichtman and Walter Greene soon convinced the leading theaters that Mary's prices were justified, and the smaller exhibitors grumblingly fell into line.

Hampton, Benjamin B. (Benjamin Bowles), 1875-1932. A history of the movies (Kindle Locations 2585-2594). Covici, Friede.

location 2225, 2831, 2920, 2933, 2882, 2895, 2907, 3734, 3749, 1772