Occidental Blvd. and Council St.

Today Known as Occidental Studios

This tiny studio is the oldest studio still in operation outside Hollywood.

It began its life in 1914 as the personal studio of famous actor/director Hobart Bosworth.

It gained fame as the Morosco-Bosworth Studio.

Photos courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

Related Pages:

Bradbury Mansion

This Queen Anne style Victorian on L.A.'s posh Bunker Hill was built in 1886 and boasted 35 rooms, 5 chimneys, and 5 turrets. In the early silent era, it was used as a movie studio by many early companies. It was Hobart Bosworth's first studio location, as well as that of Hal Roach's Rolin Co. It was where Harold Lloyd got his start. Referred to by Lloyd as "Pneumonia Hall" because of its draftiness, the once stately but now ramshackle mansion was torn down in 1929 to make way for L.A.'s Civic Center.

Bosworth Studio

211 N. Occidental Blvd.

Company Active 1913-1915

Active here 1914-1915

Hobart Bosworth was 44 years of age and a famous stage actor by the time he came to the movies. As an actor, Bosworth toured the world performing Shakespeare, as well as directing, and writing stage plays.

Born in 1867, he ran away from home at an early age, spending much of his youth on the high seas. He gained a life-long love of the ocean. Eventually landing in San Francisco, he began his acting career, making his way to New York and the Broadway stage.

Just as his career was taking off he contracted tuberculosis and he spent much of the next several years in and out of hospitals and sanitoriums. Though he recovered, he would spend the rest of his life in fragile health. But he could not shake the desire to be an actor and in the relative cold of New York his health would suffer, so he made his way west to where he could take advantage of the warm, sunny weather while getting his start in the movies.

His first movie work was with Selig Polyscope Company, one of the largest producers in the country. He starred in the very first movie filmed entirely on the West Coast, The Count of Monte Cristo, and thus was forever known by the nickname, "the Dean of Hollywood."

He also found he had the talent to direct and both started in and directed a number of films for Selig. Then, at 46, he decided it was time to strike out on his own. He wanted to produce and direct for himself, so he formed Bosworth. Inc. (aka Hobart Bosworth Productions).

He incorporated the company on July 31, 1913, and opened the doors for business on August 8 with Bosworth as company President and his associate Frank A. Garbutt as his Vice President. Bosworth initially located the company in an old house, The Bradbury Mansion in downtown Los Angeles (long since torn down), using a 20 x 25-foot stage constructed in the rear of the property. The mansion was a popular place for use as temporary headquarters for several early production companies, including Rolin Company, later known as Hal Roach Studios. Chaplin finished his famous Essanay pictures at the mansion, and Mary Pickford made her first version of Tess of the Storm Country there.

The Bosworth Company was formed for the express purpose of transforming Jack London's stories into movies. Bosworth and London were friends. Their first production was London's Sea Wolf. (See the sidebar below for the controversy surrounding this film).

Bosworth builds a studio.

In 1914 Bosworth constructed a formal studio at the corner of Occidental Blvd. and Council Street close to downtown Los Angeles. Initially, it occupied half a city block bound by Hyans on the north, Council and the south, and Occidental on the east (see the map section below).

Motion Picture News described it: "...and the firm moved into a new fireproof studio erected to embody all the valuable features of the leading film plants. The assembly of structures consisted of a glass covered stage, a concrete fireproof laboratory with a capacity than thought to be greatly in excess of any future needs, a long double-decked row of concrete, white enameled dressing rooms with running water in each room and finished in model fashion, a wardrobe building, a director's building and a 'prop' warehouse."

It was here that Bosworth produced several more of his Jack London features.

Morosco-Bosworth Studio

211 N. Occidental Blvd.

Active 1915-1918

On November 9, 1914, The Morosco Photoplay Company was formed by famous Los Angeles and San Francisco theatre impresario Oliver Morosco and business associate John Cort. The new company "joined" the Bosworth Company to produce at the Occidental and Council studio.

Oliver Morosco was born Oliver Mitchell on June 20, 1875, in Ogden, Utah. His parents divorced when Oliver was still a toddler, and his mother, Esmah, moved her two young sons to San Francisco. At the age of six the Mitchell brothers, Oliver and his three years elder brother, Leslie, were hired by San Francisco theatre impresario Walter Morosco to perform as acrobats in one of his shows. Walter Morosco made arrangements with Esmah Mitchell to become the boys' foster father, and they took his last name.

When Oliver was sixteen, Walter Morosco bought several theatres and made Oliver the manager of two of these, beginning Oliver's own career as a theater impresario. In 1899 Oliver Morosco moved to Los Angeles and began taking over the leases of troubled theatres and managed to turn them around. He opened several theatres of his own, and entered into an agreement with rival, David Belasco, to take over management of his west coast theatres. By 1906 he began to produce plays on Broadway.

The next step was to go into the motion picture business.

The Morosco-Bosworth Studio needs to stretch.

The Oliver Moroso Photoplay Company officially incorporated November 9, 1914. In December 1914 Morosco had fully "absorbed" the Bosworth Company, and the combined firm purchased property south of Council St. halfway to 1st St. (now Beverly Blvd.), where they built a large open-air stage 75 feet by 96 feet, on the property for the shooting of spectacle scenes. He also built a large carpentry shop alongside the stage. The growing studio became known as Morosco-Bosworth (or Bosworth-Morosco, as the case may be).

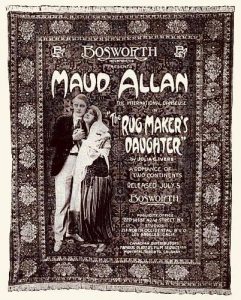

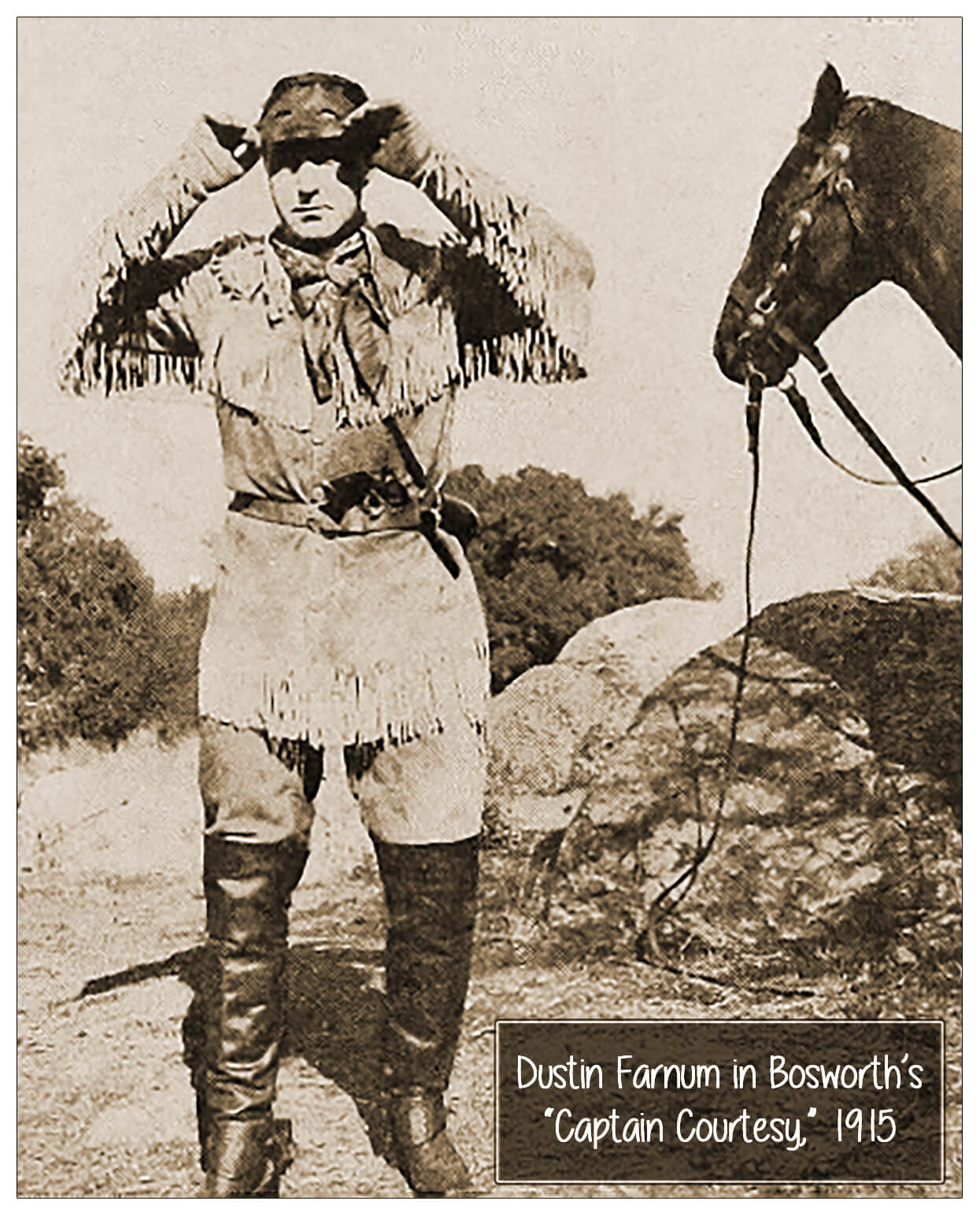

One of the first production to use the new stage across Council was Bosworth's Captain Courtesy starring famous stage and screen actor, Dustin Farnum. On the stage was built a scaled reproduction of the San Fernando Mission (of the California mission system) where a spectacular scene saw Farnum, mounted on his trusty steed, crash through a magnificent stained glass window. This was the grandest film so far produced by Bosworth. Other films shot on the stage were Morosco's Peer Gynt and Davey Crocket, (Pallas production directed by William Desmond Taylor) and Bosworth's The Rugmaker's Daughter.

At the same time, in January 1915, Morosco ordered to be built a fully enclosed glass stage on the main lot. A new 60-foot by 90-foot glass and steel stage with a complete lighting system was built in a record-breaking two days. In May it was expanded and improved until it filled all the empty studio land on the north side of Council St.

In September of 1915, the studio was pushed further south, all the way to 1st St., which was used for additional outdoor shooting and open-air stages. The Motion Picture News exclaimed in September 1915, "When the studio was built the architects took pains to anticipate what at the time was thought to be any possible growth for the next ten years, but the activity has unexpectedly increased by such leaps and bounds that now at the beginning of the second year there is already an imperative cry for more room."

Bosworth moves on.

Though Hobart Bosworth remained a part of the company, in August 1915 he moved his production unit first to Carl Laemmle's Universal City Studios, and then in 1916 to San Mateo in Northern California where he constructed a small studio on city-owned property.

By 1920 Cecil B. DeMille had taken over Morosco Company as President and general manager.

The Balboa Studio vs. Bosworth Lawsuit

Bosworth, Inc. was formed in 1913 with a single purpose in mind: to produce The Sea Wolf, a novel by the famous writer, Jack London. The old Bradbury Mansion was rented for the production.

In April of 1913, even before production had started for the brand new Balboa Amusement Producing Company at the Long Beach studio, owner H.M. Horkheimer signed a contacted with popular writer and adventurer, Jack London, to produce screen versions of his novels.

Work immediately began at Balboa on bringing two novels to the screen, but in October London presented Horkheimer with a copyright infringement lawsuit.

London decided he would rather have his friend and Balboa Studio competitor, Hobart Bosworth, have exclusive rights to turn his novels into films. Horkheimer claimed he had a signed contract with London. This was apparently true.

London's claim was that he could break the contract with Balboa and give a new contract to whomever he chose, as he held the copyright on the work. Balboa argued what we now call "fair use" and London argued copyright infringement law. Copyright infringement law won and cost Balboa not only the expenses already incurred during the production, but future potential earnings, and a loss of prestige in the business.

Bosworth signed a contract with London for the production of many of London's stories and immediately went into production on The Sea Wolf at the Bradbury Mansion and San Francisco.

The problem for Horkheimer and Balboa, it appears, is that he hired a copyright attorney to defend them instead of a contract attorney. Under contract law, he might have won.

The result was a landmark decision, changing in the way copyright law was enforced giving advantages not already in law to copyright holders. This suit changed the very nature of the relationships between copyright holders and the people they contracted with.

(editorial: The suit also revealed London's lack of integrity.)

Pallas Studios

201-205 N. Occidental Blvd.

Active 1916-1918

In August or September of 1916, after Hobart Bosworth left for the Bay Area and Frank A Garbutt became the company and studio President, he renamed the plant Pallas Studios and started his own production unit, Pallas Pictures. In an arrangement similar to Bosworth's Garbutt shared the facility with Oliver Morosco's company and drew from the same stable of actors, directors, crew, and staff. The studio was often referred to Morosco-Pallas Studio.

One of Pallas' first hires was up and coming director William Desmond Taylor, who would later gain (unwanted) fame as the victim of murder, still an open case to this day. Taylor directed Mary Pickford and his protege Mary Miles Minter, and established star Dustin Farnum all to great successes, and he became one of Pallas' and the industry's top directors until his untimely death. He became known for his ability to motivate actors. Had Taylor lived, he quite possibly would have rivaled Griffith and DeMille in Hollywood stature. After his death, he became a footnote in history.

The studio continued to grow and was now one of the largest in the Hollywood area (though tiny by today's standards).

click either to enlarge

Huge Merger, 6 Companies Under One Ownership

Famous Players-Lasky-Morosco-Pallas-Paramount

Adolph Zukor was an astute businessman. He established Famous Players Film Co. in 1912 with studios on both coasts. Jesse Lasky Feature Play Company came along a year later, a west coast company. It had three owners: Jesse Lasky, Cecil B. DeMille, and Samual Goldfish (later Goldwyn). Both companies proved to be powerhouses, having the largest studio facilities on either coast.

In 1916 they merged into the most productive studio in the nation, Famous-Players-Lasky. It had a studio in Hollywood, at Selma and Vine, known as the Lasky Studio, and another in New York, New York, known as Famous Players Studio. Zukor emerged as president of the combine, and guided hos partners into a very powerful movie industry company. Zukor was powerful. Very, very powerful.

Meanwhile, a few miles away, another studio was establishing itself as a power in the industry. Bosworth, Inc. built the studio at Occidental and Council in 1914, and in 1915 Morosco Photoplay Company bought into the studio. In 1916 Bosworth moved out and Pallas Pictures was established by Bosworth's former partner. Morosco and Pallas both occupied the growing studio lot. By 1917 the studio had grown into one of L.A.'s largest and most productive.

Paramount Pictures Corp. was founded in 1914 by W.W. Hodkinson by merging a dozen small companies into the nation's largest movie exchange (film distribution company). They were the first to go nationwide, and the first to provide financing to movie producers. Adolph Zukor began buying up available stock in Paramount in 1915 and by mid-1916 had acquired a controlling interest. He ousted Hodkinson in a hostile takeover and become the company's President. After the merger with Jesse Lasky's company, Zukor sold his Paramount interests (at a profit) to the Famous Players-Lasky company.

In mid-1916, Famous Players-Lasky merged with both Mososco and Pallas, and bought their studio at Occidental and Council, giving the company 4 production units and 3 studios, plus the nation's largest film distributor, Paramount. Zukor then started a new distribution brand, Artcraft. All six companies had their own identities, brands, and operations. They operated, for the time being, as separate but equal.

In 1926 they finally merged all the companies into one entity and moved to their big new studio on Melrose Ave. But it wasn't until 1933 that the conglomerate finally changed its name to what we know today as Paramount Pictures Corp.

Selznick takes over the Pallas lot

Select Pictures

201 Occidental

1918-1920

Lewis J. Selznick, or L.J., as he liked to be called, was an upstart in the industry and built his business quickly and in very unconventional ways (read more about Selznick here). He loved to see his name in lights and in the press. He was the only big mogul to put up billboards featuring his name. He never missed an opportunity to bang his own drum.

Selznick and Zukor fiercely disliked one another. While Selznick liked taking jabs at competitors, he never missed an opportunity to poke a finger at Zukor, in private or, more often, in the press. No one was safe from Selznick'sttacks, but he was a particular thorn in Zukor's side.

So it took the industry by surprise when it was announced in the press that Zukor and Selznick had combined forces. Zukor offered Selznick a cool half-million for a 50 percent stake in his Selznick Pictures. Zukor lured Selznick in with a promise of peace and prosperity, and a settlement of the war. Selznick would remain as President of the company.

The new name for the firm was to be Select Pictures. The industry was curious. Puzzled even. As for Lewis J. Selznick, he thought he finally had a piece of the Zukor empire. He thought he had Selznicked Zukor.

After the allure of the money wore off and Selznick had a chance to think about it, he realized what Zukor had done. He did not own a piece of the Zukor empire. No. Selznick's operation was not merged in with the Zukor family of companies. Instead, Zukor owned half of Selznick's little company, operated separately. AND...the company was to be renamed Select Pictures. Selznick had lost the one thing that separated him from the other movie moguls and motivated him to work hard. The Selznick name was no longer to be on any advertising, on any building, on any film produced under the Select banner. Instead, they were to use only Select Pictures above the title. Selznick's name would no longer be in the public eye, in lights. He lost his leverage, he lost his fame. He feared nobody would remember who he was.

The whale ate Jonah. Selznick got Zukored.

For two painful years, Lewis J. Selznick operated Select Pictures on the Pallas Company studio lot. Despite this, Selznick's business and marketing skills caused he and the company to prosper financially. The combined movie geniuses of Selznick and Zukor led to success for Select Pictures. Even though he remained in New York, L.J. Selznick was, for this period of his career, a Hollywood producer.

Under their contract, Select was to make mainstream fare with lesser-known players while the Morosco and Artcraft labels would make the higher quality films with the bigger stars. Selznick did not know how to operate that way. He had always had just a few big stars under contract, each making a few big pictures with high priced tickets. He did the best he could, made a lot of low and mid-budget pictures. He prospered and made money for the company, but he was not content. So almost immediately he began to plot to bring in big stars making his usual high budget features, like he had always done before. Zukor objected to this but as Selznick was the managing partner there was little he could do.

Meanwhile, in a quiet maneuver, Lewis J. Selznick worked with his eldest son, Myron, to create a brand new Selznick Pictures. Operating in secrecy, Myron lined up financing and star contracts.

In 1920 Adolph Zukor made Lewis J. Selznick an offer. He asked Selznick for a full million dollars for Zukor's 50% stake in the business. Selznick took the offer and handed Zukor a million dollars. Zukor had made a lot of money from the Selznick genius, and was glad to be rid of him, thinking Selznick would just fade from the business. He was wrong.

Selznick retreated to the comfortable confines of New York, ramped up his new Selznick Pictures company with Myron, changed Select into a major film distributor, and put the Selznick name back in lights.

Realart Pictures

Realart Studio

201 N. Occidental

1919-1922

Once S

elznick moved out, Zukor filled it with another new company, Realart Pictures to fill the market for Select's kind of movies. Realart commenced business on June 9, 1919, with Select's general manager, Arthur S. Kane staying on in the same role as did others from the Select staff. Big star Mary Miles Minter, as well as stars players Bebe Daniels, Alice Brady, Wanda Hawley were among the talent Zukor brought in. As well he brought in veteran director Allan Dwan and up-and-coming star director William Desmond Taylor. As usual with Zukor, he stayed behind the scenes and neither confirmed nor denied any asso

ciation with Realart. The pictures were well made, well-received, moderately priced, and so Realart had no trouble establishing itself as another successful unit of the Zukor and Lasky empire.

This replacement for Select's revenues was relatively short-lived. It was shut down when William Desmond Taylor was found murdered in his home on February 1, 1922. They finished out the schedule the best they could, then Adolph Zukor shut it down and closed the studio doors. Famous Players-Lasky absorbed its assets. Its films continued to be distributed as first runs throughout 1922. The studio was idle until it was opened under its new name, Paramount-Wilshire Studio.

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

Paramount-Wilshire Studio

Wilshire-Paramount Studio

201 N. Occidental

1922-1933

Once Realart was absorbed into the parent company, Famous Players-Lasky, the studio once again changed names. In February 1922 Jesse Lasky, first V.P. and head of production for the company that bore his name, announced that the lot would be known as Paramount-Wilshire. Unlike Realart, Wilshire would be a studio only, no production unit bearing the same name. It would be used for overflow from the Vine Street lot and as a rental lot for outside producers.

Lasky shut down the lot and undertook another significant renovation making sure everything was ready for whatever production needed the facility. The first film to be shot at the newly renovated Wilshire lot was Blood and Sand starring Rudolph Valentino and directed by Fred Niblo and Dorothy Arzner.

At some point, exactly when it is unclear, the Famous Players-Lasky group stopped using it for their own productions. As they built their big new Paramount Studios on Melrose Ave. in 1926 that date would make sense. It was soon after that a series of producers and production companies took up residency, many times renting office and stage space simultaneously.

Among the companies that based themselves at the Paramount-Wilshire studio are Max Du Pont's Vitacolor lab, Multicolor Films Corp., Cinecolor, Inc., Prizmatic Productions, Roy Davidge and Co., lab, W.J. Worthington, American Studio, Andrew J. Callaghan Prods.

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives click to enlarge

St. Anne's

The land south of Council St. was sold to St. Anne's in the mid-1940s. It is the flagship location for the organization, which was founded in 1908 as a "home for pregnant young women with nowhere else to turn." Today their mission also includes providing high-quality housing, early childhood education, and mental health services with locations all over the Los Angeles area.

St. Anne's is sponsored by the Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Heart, a catholic ministry.

They have built a modern facility on their 5-acre former movie studio property.

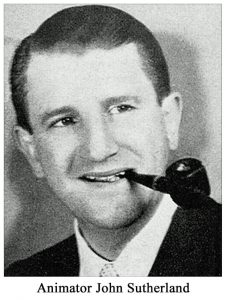

Sutherland Studios

201 N. Occidental

1945-1962

In 1945 the studio was bought by cartoonist John Sutherland. Originally known as Morey and Sutherland Productions, in 1950 the company was reorganized into John Sutherland Productions. Famous cinematographer Byron Haskins was on his board of directors. Sutherland owned it until the 1960s when it was bought by famed producer/director Robert Aldridge.

Sutherland Productions, in 1950 the company was reorganized into John Sutherland Productions. Famous cinematographer Byron Haskins was on his board of directors. Sutherland owned it until the 1960s when it was bought by famed producer/director Robert Aldridge.

John Sutherland was a popular mid-century animator of educational and industrial cartoons whose name might not be familiar, but his style is readily identifiable. Sutherland began his career as a producer of Mickey Mouse shorts for Walt Disney in the early 1930s. One of his best known animated works was the documentary "A is for Atom" produced for General Electric and shown in elementary schools all over the country during the 1950s. He also produced a variety of animated commercials, including for Tide Laundry Detergent and Ford Motor Company. He also made a series of educational cartoons through a grant from the U.S.Department of Education. Some of his animated featurettes were made for M.G.M while he also produced a series of cartoons commissioned by Harding College (now Harding University) which were adult-themed, anti-communism, pro-capitalism in nature. His themes were generally patriotic. His style was reminiscent of the Hanna Barbara cartoons.

Mr. Sutherland also produced several live-action feature films for Universal and others. In 1941 Sutherland voiced the adult Bambi and his wife, Paula Winslowe, was the voice of Bambi's mother.

Mr. Sutherland was born Sept. 11, 1911, and died Feb. 11, 2001.

Either just before or just after Morey and Sutherland acquired the studio, St. Anne's Home for Young Women purchased the studio land south of Council St. The studio was back to its original footprint occupying the eastern two-thirds of the block bordered by Hyans on the north, Occidental on the east, and Council on the south.

Noonan-Taylor Productions

201 N. Occidental

1963-1967

Tommy Noonan was a familiar face during the 1950s and 60s as a "B" feature supporting comic. He is perhaps best remembered as Marilyn Monroe's love interest in Gentlemen Prefer Blonds as well as Judy Garland's sidekick in A Star is Born. He was also the erstwhile partner of Peter Marshall (of Hollywood squares fame) in the ill-fated comedy duo Noonan and Marshall. Noonan was the half brother of Osar nominated actor John Ireland.

By the early 1960s, Noonan's career was on the slide, so he hooked up with partner Donald Taylor to produce a couple of forgettable movies at 201 Occidental Blvd. In 1963 the first was Promises...Promises! (not the Promises, Promises you are thinking of, but another one) starring Jayne Mansfield as her star was fading. Noonan wrote and produced the film as well as playing Mansfield's love interest. The following year he wrote, produce, and directed Three Nuts in Search of a Bolt with has-been sexpot, Mamie Van Doren.

Promises...Promises! had a single movie history distinction. It featured the first nude scene by a mainstream actress (Mansfield) since the Hayes Code came to be in the early 1930s.

Tommy Noonan occupied the studio in one name or another, until his lease ran out it in 1967. He died in 1968 of a brain tumor at the age of 47.

Aldrich Studios and

The Associates & Aldrich Co.

201 N. Occidental

1968-1974

By the time Robert Aldrich bought the studio, he was already a powerful and well respected independent producer/director known for his ability to motivate actors and to bring high drama and tension to the screen. His string of hits included Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, Hush...Hush Sweet Charlotte, Sodom and Gomorrah, The Dirty Dozen, Kiss Me Deadly, Flight of the Phoenix. He had worked with major stars like James Stewart, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Olivia de Havilland, Burt Lancaster, Edward G. Robinson, Gary Cooper, Mary Astor, Lee Marvin, Ernest Borgnine, Donald Sutherland, and many more.

Robert Burgess Aldrich was born on August 9, 1918, in Cranston, Rhode Island into a wealthy family of bankers, business executives, socialites, and politicians. His father, Edward Burgess Aldrich, was a newspaper publisher and was influential in Republican Politics. His grandfather, Nelson Aldrich, was a self-made millionaire and a member of the United States Senate. Fame and fortune graced his family dating back to the Revolution, where, among his ancestors were the founder of the Rhode Island Colony, and a Revolutionary War general. Aldrich was and part of the Rockefeller extended family, as well. Standard Oil heir John D. Rockefeller was his uncle and former Vice President Nelson Rockefeller was his first cousin.

However, during the depression, he began to question the propriety of his family's wealth and power. He contrasted it against the millions of struggling working-class people who didn't have enough to eat or a place to live and suffered while his family prospered. This led to his sympathies for left-leaning social and political causes and associations with several people who had an inevitable confrontation with the House Un-Amerian Activities Committee during a dark period of American history.

Rejecting his family tradition of finance and right-wing politics, Aldrich was disinherited. He got his start in the film business the old fashioned way: he started at the bottom. In spite of having connections that could have led to executive positions in the front office of any studio, he worked his way up. Beginning at RKO in 1941 as a production clerk, he studied the filmmaking craft with some of the great producers and directors. By the mid-40s he had worked his way up from second assistant director to first assistant director. Some of his assistant director work included Charles Chaplin on Limelight, the remake of the noir classic M for Joseph Losey, The Story of G.I. Joe starring Robert Mitchum and directed by William Wellman, among many, many other classic films.

He went independent and spent time with John Garfield's Enterprise Productions, when Garfield broke from the studio system. This allowed Aldrich to establish relationships with actors, directors, cinematographers, and other craft people, which would serve him well when he established his own company, The Associates & Aldrich Company, in the early 1950s. As a result, he had a pool of Hollywood's best talent to draw from. Talent that knew him, trusted him, and were anxious to work with him.

Here at 201 Occidental, Aldrich produced several significant films. The Killing of Sister George starring Suzanne York and Beryl Reid, The Legend of Lylah Clare with Kim Novak and Peter Finch, and What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? starring Geraldine Page, Ruth Gordon, and Mildred Dunnock.

Aldrich had big plans for renovating the lot, adding three large, new stages and remodeling/redesigning the buildings, and upgrading and beautifying the grounds with plenty of off-site parking. Unfortunately, those plans never materialized. He was able to remodel and beautify the existing 8,000 and 9,000 square foot stages and other buildings but it was left to the current owner to make additional major improvements.

After leaving the studio behind, Robert Aldrich went on to produce and direct many more pictures. Even after a string of box office flops, in Hollywood famous for casting aside those out of favor, he refused to be ignored and came back with a series of winners, including the prison comedy The Longest Yard starring Burt Reynolds, Eddie Albert, and Bernadette Peters, as well as the film version Joseph Wambaugh's novel The Choirboys with Loius Gossett, Jr. and Charles Durning, Twilight's Last Gleaming with Burt Lancaster, and another Reynolds pic, Hustle.

He was described as having an "aggressive and pugnacious film-making style, often crass and crude, but never less than utterly vital and alive." Robert Burgess Aldrich died December 5, 1983, at the age of 65. He will be remembered as one of the greatest and boldest independent producers and directors, whose work rose above most others.

Video Cassette Industries

201 N. Occidental

1975-1980

Video Cassette Industries, known as VCI, moved onto the lot in 1975. They inherited a wholly modern, well-oiled film studio that they retooled for use producing and distributing for the video market. New lighting equipment for film and videotape has been installed and more than fifty production offices on the lot are available as well as projection, editing and portable dressing rooms, etc. Independent producers use the facilities for TV pilots, commercials. educational courses, including children's bilingual programs. All of these are produced on videotape cassettes in a variety of sizes and can be transferred to all film requirements.

In 1980 the studio was bought by Larry Sullivan's Sullivan and Associates Productions doing commercial films and promotion for ABC TV Network. In 1987 the studio was known as Global Studios doing commercials and rehearsal rentals.

Occidental Studios

Occidental Entertainment Group Holdings

201 N. Occidental

1989-present

In 1989 Albert Sweet, a Los Angeles business investor, bought the studio and, over a period of years, created a "studio" of large proportions. Though 201 Occidental is the flagship, the company's headquarters are actually smack in the middle of Hollywood proper with 15 additional stages scattered across Hollywood, Los Angeles, and the Valley. They have approximately 150,000 square feet of studio space, plus production offices, and support servics covering more than 17 acres all under the Occidental Entertainment Group holdings banner.

It included 4 stages here at 201 Occidental and, at present 11 additional stages and other Occidental owned companies spread across the Hollywood area. Though this lot is Occidental's flagship studio complex, the headquarters are located in the middle of Hollywood proper.

In 2011 the company built is pièce de résistance, and a large new state-of-the-art stage on the main campus, the first new construction on the lot in many decades. The company also owns real estate across Occidental for off-site parking and a small home at the opposite end of the block at Council and Reno Streets.

Additional research courtesy of Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives